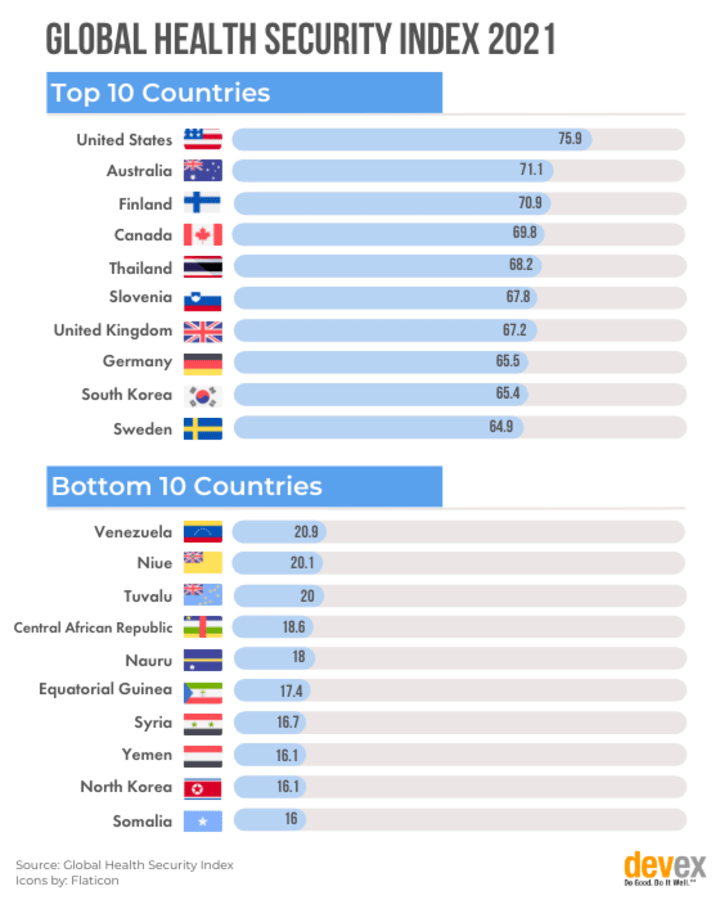

The United States again topped this year’s Global Health Security Index, and several countries across the globe also improved in their rankings. But as COVID-19 has shown, a high score doesn’t guarantee a robust response in a crisis.

The GHS Index examines countries’ global health security capacities in preventing, detecting, and responding to a health threat. It also assesses countries’ health systems, commitments to address those gaps including financing, and their overall risks and vulnerability to biological threats.

The State of Global Health Security

What is the state of global health security today, and where does it go from here? Read our new special report “The State of Global Health Security” for a look at what we found.

But COVID-19 served as a reality check for countries and raised questions on the value of preparedness assessments such as the Joint External Evaluations and the GHS Index, which in 2019 gave high scores to the U.S. However, the U.S. response to the pandemic has been characterized as poor, with COVID-19 deaths in the country now close to 800,000, the highest globally.

Jessica Bell, senior director of global biological policy and programs at the Nuclear Threat Initiative and one of the authors of the GHS Index 2021, told Devex that the index is “a step in identifying where the gaps are. The goal here is to lead to conversations that stimulate this dialogue around how to address these gaps.”

‘Dangerously unprepared’

According to the latest Global Health Security report, published Wednesday, countries remain “dangerously unprepared” for future epidemic and pandemic threats. The average country score globally was low, at 38.9 out of 100, and not a single country, including the U.S., scored higher than 80.

For the 2021 report, the GHS Index team took stock of the different factors affecting the COVID-19 response. They added 31 new questions in the index to assess countries’ laboratory strength and quality, supply chains, national-level policies, and plans, as well as government effectiveness, which the pandemic has shown to be vital during an emergency.

In terms of government effectiveness, only 16 countries are in the top tier, scoring 80.1 and above. These countries are Andorra, Australia, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, New Zealand, Norway, San Marino, Singapore, Sweden, and Switzerland.

The index team also discussed the effect of factors such as public trust in government on countries’ abilities to respond to COVID-19.

Sign up for Devex CheckUp

The must-read weekly newsletter for exclusive global health news and insider insights.

The average overall country score for public confidence in government is 44.4 out of 100, which isn’t a “good news story,” Bell said. Stronger public confidence in their governments plays a key role as countries implement their responses, such as vaccination.

“We remind all countries that performance on the GHS Index is measured on an absolute scale. Deficiencies in any area can be crippling. Countries that have risk factors, such as low public trust, must find ways to address this at the onset of an event. Or at the very least, not exacerbate it, as we saw U.S. leaders do,” she said.

Who did well?

The U.S. may be number one in overall rankings, but it ranked lower in specific categories, placing third in early detection and rapid response, and 31st in overall risk environment.

Brunei had the highest increase in overall score of 10.5; it moved 47 spots up in the ranking, now placing 64th from 2019’s 111th spot.

Some countries also improved their capacities in specific categories and moved up the ranks. São Tomé and Príncipe received a 14.4 increase in its score on prevention, moving 50 spots up in the ranking for that category, and now placing 145th.

Under the rapid response category, Angola and Kiribati also showed the largest increases in their score at 10.7 and 10.1, respectively.

Meanwhile, among low-income countries, only the Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda have shown some evidence of having a testing plan in 2021.

Bell said new scores and rankings have been calculated for each country for 2019 using the updated framework, making it possible to make comparisons on countries’ progress.

But she cautioned that an increase in countries’ preparedness capacities does not necessarily translate to successes in protecting their populations from COVID-19. The report emphasizes that the GHS Index cannot be used as a predictive tool on how well countries will perform in a crisis.

For example, the U.S. has a strategic national stockpile of personal protective equipment, but this was only on paper, and the government did not heed intragovernmental calls to replenish its PPE supplies after the 2009 swine flu pandemic. Countries’ failure to address high levels of public distrust in government also hindered their ability to implement tests or encourage people to get vaccinated for COVID-19, she said.

“Further, some countries had functioning capacities to minimize the spread of disease, but political leaders opted not to use it, choosing short-term political expediency or populism over quickly and decisively moving to head off virus transmission,” she added. “The U.S. and Brazil actively discussed [the] pursuit of herd immunity as a strategy rather than trying to stop the spread of the virus.”

Financing a ‘disappointment’

The index also reveals that pandemic preparedness remains underfunded. A total of 155 out of 195 countries have not allocated national funds within the past three years to improve their capacity to address epidemic threats. And among low-income countries, only Guinea-Bissau and Uganda have shown evidence of allocating funding for this purpose.

“We remind all countries that performance on the GHS Index is measured on an absolute scale. Deficiencies in any area can be crippling.”

— Jessica Bell, senior director, Nuclear Threat InitiativeIn addition, 90 countries have not fulfilled their full financial contribution to the World Health Organization within the past two years. Fourteen of these are high-income countries: Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Chile, Cyprus, France, Israel, Kuwait, Nauru, Palau, Saudi Arabia, Trinidad and Tobago, United Arab Emirates, U.S., and Uruguay.

Bell said the lack of progress on financing pandemic preparedness was not surprising “but disappointing.”

“Overall, the 2021 index shows a very slight increase in financing. While it’s not surprising that longer-term financing wasn’t prioritized, it shows that the focus is on short-term response and recovery rather than a combination of rapid response with more sustainable financing towards health security,” she said.

The lack of significant change in pandemic preparedness capacities across countries worries her, especially since improving countries’ health security capacities takes time, “consistent attention and action.”

But she hopes that countries will maintain the capacities that they were able to develop in response to COVID-19 and ensure they can be used for future crises.

“The 2021 GHS Index shows a lack of priority, but it also shows that countries are able to develop capacities on the fly. The fact that rapid response is able to be implemented — across [country] income groups — is very encouraging and it will require continued work to make sure that these capacities can be used for broader infectious disease threats,” she said.