SAN FRANCISCO — Good intentions are never enough. That was one of the messages from Tim Hanstad, CEO of philanthropic organization the Chandler Foundation, while speaking on a Devex webinar about ways funders can support local solutions.

When funders do not understand what the problem is, as it is perceived by the people they are trying to help, they can actually cause harm, he warned.

Hanstad was one of three leaders in philanthropy who joined Devex in a webinar on how to move from funding from afar to supporting local solutions. There is a misalignment between where the majority of philanthropic resources lie and where they need to be spent to effectively address many global challenges, he said.

Hanstad and panelists from India-based strategic philanthropy foundation Dasra and global collaborative for systems change Co-Impact shared ways funders can close the distance between themselves and the solutions they seek to support.

Taking the field approach

Over the next five years, India’s economy is expected to double. But as the country approaches higher middle-income status, official development assistance will no longer be an option.

Trickle-down economics alone will not be sufficient for India to meet its development goals, said Neera Nundy, co-founder and partner at Dasra: “How do local funders fund local solutions?” she asked.

India needs an additional $60 billion annually at a minimum to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, and philanthropists can play an important role, but they must also “leverage deeper pockets,” including the government and private sector, Nundy added.

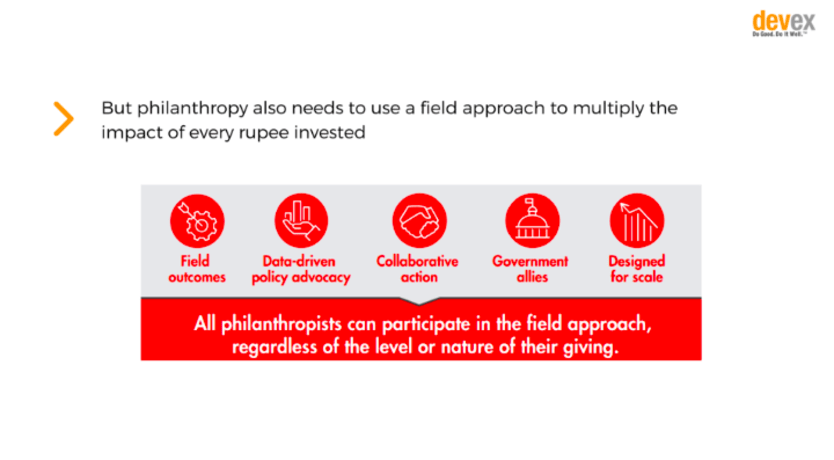

And the needs extend beyond financial resources, she said, referencing the field approach her organization takes, with a focus on collaborative action, outcomes, and design for scale.

Dasra launched 20 years ago, and its model has helped to inform a number of models focused on collaborative philanthropy and systems change, like Co-Impact, which launched in 2017.

But Nundy pointed to the hard work social enterprises as well as philanthropists must do to stay locally relevant. Many successful organizations can begin locally, but then when larger institutional funders come in, they may become more distant from community voices as they scale, she said.

Making feedback meaningful

Before moving into philanthropy, Rakesh Rajani, vice president of programs for Co-Impact, worked in Tanzania, where he is from.

He shared a story of failure from one project he was involved with that asked people to use SMS to report broken water pumps so that authorities would fix them.

When Rajani and his team asked people why they were not using the service, they said they did not think the government officials responsible for fixing these water pumps would really do anything.

Stories like these point to several reasons many development projects fail: The problems are defined by experts who do not experience local contexts, they are blind to the priorities of the people they are trying to serve, and they are more enamored by the power of the technology than the complexity of the problem, Rajani explained.

But there are ways that funders can get this right, for example by building effective feedback systems into their programs, Rajani said.

He expanded on ways Co-Impact and its partners do this, mentioning some of the recipients of the first round of Co-Impact grants.

Some funders ask for extremely detailed budgets and want control over how every dollar gets spent, whereas Co-Impact has strategic conversations with the local leaders they support, then provides flexibility as to how the money is spent, Rajani said.

“Instead of having a blueprint that we control and they must follow, we ask ‘what mechanisms do you have in place to course correct, and learn and adapt your practices?’” he said.

Co-Impact also asks for regular feedback on how it can improve and better support organizations, Rajani said, who is currently seeking concept notes for round two grants.

Understanding how outsiders can add value

Drawing on his experience at Landesa, a nonprofit focused on land rights he started and led, Hanstad’s call to action for the webinar audience was to be ready to respectfully disagree with donors.

“Sometimes I think doers are so eager to get the money that they play into the power dynamic and don’t call out donors,” Hanstad said.

Hanstad, who leads a foundation started by a core partner at Co-Impact, and Rajani both shared a number of practical ways to change the power dynamics between donors and doers.

Rajani said that to make the doer and donor relationship more equal and mutual, the grantee should set the agenda and rules of the game, and feel comfortable saying “no” to the funder. The funder should be able to tell stories of what they have learned from the grantee and how that would change their mind.

Hanstad added that it is important for the sector to talk about power and privilege, but noted his concern that some people who may be far away from the problems they aim to solve and solutions they aim to support could become discouraged from doing this work.

“That is also problematic,” he said.

Nonlocals can provide important support, he said, so long as they follow some of the steps that he, Rajani, and Nundy outlined.