3 tips for NGOs considering a foray into drone use

Overuse or misuse of drones in the past few years has left many aid groups wondering how to move forward. Devex caught up with three experts in the space to find out what organizations need to know now.

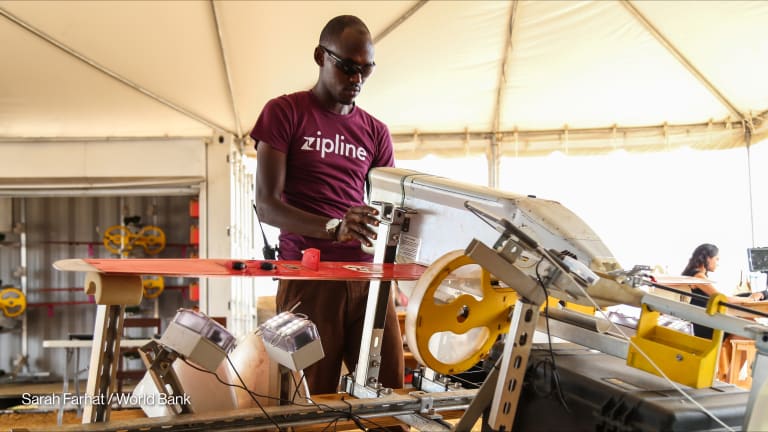

BANGKOK — Though the use of drones for humanitarian aid is still relatively new, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies has been heavily exploring how best to utilize the technology. The world's largest humanitarian network is currently experimenting with drone use across several countries and sectors, including a partnership with Land Rover to create a roof-mounted drone that can take off and land while the vehicle is moving, a concept being tested in Austria. A partnership with aerospace company Airbus, meanwhile, is looking at medium-range, light-payload cargo drones to deliver medication and vaccines. Aarathi Krishnan, regional innovation and futures coordinator for the IFRC in the Asia Pacific, is the first to say that the organization must be careful to adopt drone use only if it provides a valid addition to existing efforts — and only if teams are first properly trained in how to utilize emerging tech. “Something that’s really clear to us is we have to build the right types of skill sets within our own organization because it’s not just about piloting drones; it’s about analyzing the imagery that comes out of it as well and being able to use that analysis for effective decision making,” Krishnan said. Following limited use in Haiti in 2010, after Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in 2013, and in the aftermath of Nepal’s earthquakes in 2015, UAVs are increasingly being recognized by humanitarian organizations for their potential effectiveness in disaster response as well — especially in helping teams quickly and safely collect damage assessment information when satellite imagery can’t cut it. “I can see we’ve gone from ‘Oh no this is not good,’ or ‘This is just a fad,’ to ‘Oh OK this is happening, how do we work with this,” Krishnan said. “The conversation is changing because of how prevalent the use of it is.” At the same time, overuse and misuse of drones in the past few years have left many aid groups wondering how to move forward. While several large international nongovernmental organizations and U.N. agencies are currently puzzling over ethical use and more practical coordination, there are already key lessons learned. Devex caught up with the IFRC’s Krishnan, humanitarian drone expert Patrick Meier, and drone services company SkyEye founder Matthew Cua to find out what they believe organizations need to think about before sending a UAV into the sky. 1. First, ask if a drone is a suitable solution. Drones can be used for public health disaster risk reduction, environmental monitoring, and wildlife protection. In fact, “the scope of use cases is a lot wider than what we think,” Krishnan told Devex, listing coral reef mapping in the Pacific region and land topology surveying to address land security as other emerging uses. But just because drones can be used doesn’t mean they should. Meier suggests identifying the main social challenge you’re trying to address, then running it by an impartial expert. Through WeRobotics, Meier has set up Flying Labs, networked hubs that transfer relevant skills and appropriate robotics technologies to local partners in developing countries so they can scale the positive impact of aid, development, and environmental projects. Labs already exist in Peru, Tanzania, and Nepal, with two more planned for Senegal and Panama next year. The Flying Labs have become their own network for lessons learned, best practices, and technical support — a community of knowledge that Meier wants to share with the wider humanitarian and development sectors. “We always ask, ‘Is robotics the right technology?’ Maybe we should use satellite imagery or smartphones,” Meier said. “But if robotics makes sense, then we will identify what kind of robotic solution makes the most sense and provide professional hands-on, in-person training.” 2. Take advantage of simulations and trainings. “Nothing beats a simulation,” said Cua, founder and CEO of SkyEye, a UAV service and decision support company based in the Philippines that offers GIS mapping, low altitude aerial imagery, and deployment of low-cost UAVs. The company caters to both the public and private sectors. But no matter the client, Cua invites them for a free simulated drone intervention so they can see the drone in the air, understand the data processing, and witness the operational side, he said. As part of the simulation, Cua’s team might fly a drone over a community that an organization is working in already, then print out a map and encourage the group to invite community members to see where they live on the map. “Let’s say you are, for example, deciding where to put a multipurpose hall. You would need community consultations, and that takes a while. But with a map it’s easier to say, ‘OK everybody, take a look and decide where you want to put the hall,’” Cua said. “Most NGOs don’t have enough resources, so we provide the tools for them to direct their resources much more effectively.” Having an understanding of the ecosystem and some internal capacity to analyze the data is a good idea, and trainings are the way to gain that knowledge, Meier said. But he doesn’t see in-house drones and drone pilots as part of the future of an NGO’s makeup. “From the many organizations and NGOs we have spoken with over the years, the interest tends to be more about being able to source drone expertise rather than having it in-house because the tech changes so quickly,” he said. 3. Don’t go buy an expensive drone to get started. The process is as important, if not more important, than the technology, “so a good drone team or a good drone pilot is one who is flexible and adaptive and can do more with mediocre, low-end drones than a rigid team can do with the best drones in the world,” Meier said. In other words, a more expensive drone does not necessarily equal a better result. “This goes for the whole ICT4D space,” Meier elaborated. “It’s about the expertise in the field and the processes that are developed around the use of this tech that matters more than the tech itself.” If an organization has the bandwidth, interest, and budget, then perhaps purchasing a drone isn’t a bad idea. But execution is still tricky, especially for groups working in disaster response, Meier said: “A disaster hits, and they get overwhelmed with the usual elements of disaster response, so the drones stay in the box. So you have the drones, you have the skills, but you don’t have the time during disaster.” What’s even more problematic is when an organization is “wowed” by a new company that’s offering an unbelievable drone, Meier said. “This organization decides to invest $50,000 into a bunch of drones that end up not actually doing what they thought they were able to do,” he told Devex. “If that weren’t bad enough, unfortunately these NGOs will then say ‘Oh, clearly drones don’t work’ and just dismiss drones altogether.” It’s part of the reason Meier is focused on building local drone technology capacity — so that groups can draw on expertise from Flying Labs rather than agonizing over the technology itself, and instead focus on the data they need to make better decisions. “I think it’s still very early days. What’s very exciting is that more and more international humanitarian organizations are starting to leverage this technology,” Meier said.

BANGKOK — Though the use of drones for humanitarian aid is still relatively new, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies has been heavily exploring how best to utilize the technology.

The world's largest humanitarian network is currently experimenting with drone use across several countries and sectors, including a partnership with Land Rover to create a roof-mounted drone that can take off and land while the vehicle is moving, a concept being tested in Austria. A partnership with aerospace company Airbus, meanwhile, is looking at medium-range, light-payload cargo drones to deliver medication and vaccines.

Aarathi Krishnan, regional innovation and futures coordinator for the IFRC in the Asia Pacific, is the first to say that the organization must be careful to adopt drone use only if it provides a valid addition to existing efforts — and only if teams are first properly trained in how to utilize emerging tech.

This story is forDevex Promembers

Unlock this story now with a 15-day free trial of Devex Pro.

With a Devex Pro subscription you'll get access to deeper analysis and exclusive insights from our reporters and analysts.

Start my free trialRequest a group subscription Printing articles to share with others is a breach of our terms and conditions and copyright policy. Please use the sharing options on the left side of the article. Devex Pro members may share up to 10 articles per month using the Pro share tool ( ).

Kelli Rogers has worked as an Associate Editor and Southeast Asia Correspondent for Devex, with a particular focus on gender. Prior to that, she reported on social and environmental issues from Nairobi, Kenya. Kelli holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri, and has reported from more than 20 countries.