During a parent-teacher meeting in a primary school in Pemba, a remote island off the coast of Zanzibar, Juanito Estrada was losing his patience.

The Filipino volunteer with VSO International was appealing to the parents to help fill a shortage of desks in the classrooms to improving the students’ quality of education. But the parents wouldn’t budge. First, they argued it’s the government’s responsibility to provide the desks. Then they said they don’t have the materials to create one. And when Estrada suggested the school could provide all the necessary materials — from timber to nails — the parents claimed they don’t know how to build a desk.

“I quickly [found out] that they are not really interested in helping and making the desks and I accidentally blurted out of my desperation to get the parents support, ‘My goodness you do not know how to make desks during the day but you can make babies in the dark even without tools!’,” he narrated.

It was only after his outburst that Estrada realized what he had done: He breached the community’s non-confrontational culture. Soon, he surmised, he’d be asked to leave and that would be the end of his volunteering career — or so he thought.

“The women parents who were in the meeting started laughing and [then] everybody laughed at what I said. Then one of the ministers who were with us in the meeting whispered to me ‘thank you, you said it, nobody does it here because it is our culture not to confront our people that way’,” he recalled.

Today, 75 percent of the classrooms in the school have desks. All of them were built by the parents and made from local resources, according to Estrada, who is now employing a similar technique — using locally available materials — in his role as quality teaching adviser in the Njombe region in Iringa, Tanzania.

This is Estrada’s second volunteering stint in Africa under VSO. He used to be a university lecturer in the Philippines before deciding to become a full-time volunteer, in part to fulfil his mother’s dream of doing missionary work in the continent.

“When we were young, we would save money and send it to Africa as aid … Now, I can see how that money is being used here,” Estrada said in a documentary produced by the organization.

A roller-coaster ride

Estrada describes his volunteering work as “a cup of kahawa,” a locally brewed coffee in Tanzania with a bittersweet taste: While he finds it fulfilling, it’s not without challenges.

Estrada’s placement requires him to visit multiple schools in a month. But because of poor infrastructure, the travel time between each visit takes longer than usual. He spends an average 27 days per month on the road, which pushed him to make “very detailed plans” of his travel routes and be resourceful in replenishing materials needed for training and personal use.

Language barriers have has also proven to be taxing. In one instance, he even had to make use of his drawing skills.

“The driver was driving so fast and do not mind slowing down in the curves. I do not know how to communicate with him using the local language, since he speaks only the local dialect. So I tried to draw a turtle in my palm. I showed it to him and made a hand gesture for him to slow down. That made him laugh, and he taught me the local word for ‘slow down’,” he said.

Today, that same driver has become his friend and language tutor. And he shares: “That saves me my meager allowance for hiring and paying a professional language teacher.”

No support

Lack of government support for teachers across the six National Teachers Colleges he visits, including the Tandala Teachers’ College, however, proves to be the most challenging obstacle for Estrada.

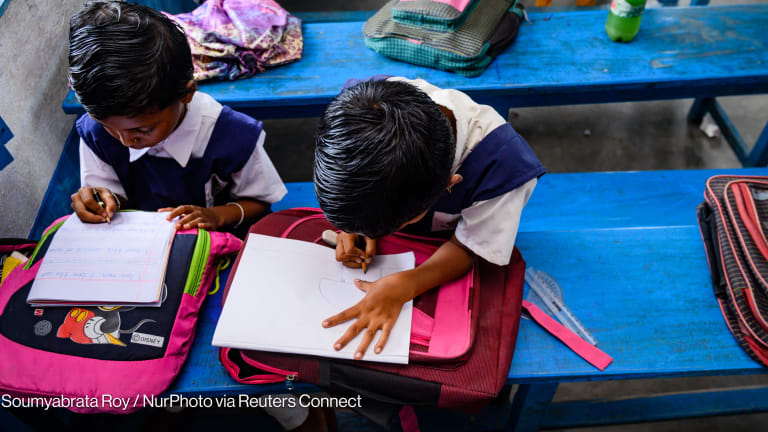

In his current role, the VSO volunteer observes class and helps train teachers. Most college tutors lack experience, as the government sends many of them off immediately after graduation. But teaching aids are also in short supply, even basic tools like chalk and paper.

Estrada had encouraged them to use the school’s natural surroundings: grasses formed in different shapes and could be used to teach simple fractions, or fences patterned after the map of Africa.

“That surprised the local communities — that there was so much resources. What [I realized] they needed was to have someone who will help them unlock their potentials, and teach them how to utilize their resources to make them self-sustainable,” he said, noting this, in the long run, would hopefully free them from a culture of dependence.

Tough times

Estrada takes the challenges he encounters as opportunities to learn, bond and integrate better with the community.

In his spare time, he hosts meals, plants, organizes info-cycling campaigns, joins marathons and hikes with the aim of raising funds for projects he is involved with. This, he explained, helps him maintain contact with fellow volunteers and develop networks for future project collaborations. But he admits it can get lonely sometimes.

Despite the advancement of communication technology, Estrada said he misses his family “when times in the placement get rough, and when I am physically tired.”

“Sometimes, you feel helpless because you cannot do anything anymore because it is beyond your capacity as a volunteer … but it helps me realize that … our ability to help and support has also its limitations, and that makes us no different with others,” he concluded.

Read more development aid news online, and subscribe to The Development Newswire to receive top international development headlines from the world’s leading donors, news sources and opinion leaders — emailed to you FREE every business day.