A global engineer education: What you need to know

The core competencies of today's global engineer go far beyond structural analysis. Find out what soft skills successful engineers possess, and how university programs are weaving the teaching of these attributes into their courses.

Traditional engineering courses are becoming increasingly varied as universities and major firms alike recognize the need to cater to the needs of a quickly globalizing world. “The field of engineering is changing. It’s no longer focused on the local type of engineering — it’s more global talk, global engineering, and the key is, how do we create global engineers?” said Bernard Amadei, the founder of Engineers Without Borders and former director of the Mortenson Center in Engineering for Developing Communities at Colorado University Boulder. “You ask engineering students today why they are interested in the degree and they say they want a meaningful education and careers.” The Mortenson Center in Engineering for Developing Communities, founded in the early 2000s, is one of the engineering programs that has popped up within the past 10 years to prepare engineering students to work in developing countries. The work requires students to dramatically broaden their skill set and frame of mind. Cathy Leslie, executive director of Engineers Without Borders, told Devex the need for global engineers is natural. “The world has become much more global, given the Internet and access and so I think it is not so much that the need has changed, it is that the opportunities in the market have changed,” she said. “And our educational structures are saying, ‘We need to better prepare for this.’” Beyond the basics When Amadei launched the Mortenson Center, he quickly recognized the need to train engineers to approach a wide range of contexts — to operate in cities to rural areas. The basic fundamentals remain the same as that of any other engineering program, but global engineers are also tasked with understanding foreign cultures and having the people skills, sensitivity and knowledge to work with local communities and leaders who might know best, for example, how to tackle the risk of a flood. Arizona State University’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering calls these traits “power skills,” or soft skills, which include communication, entrepreneurship and ethical behavior. They are woven into the curriculum at the large university, home to about 19,000 undergraduate and master’s students. One program at ASU, Global Resolve, has graduated 600 students since it launched in 2006. Its students have constructed projects like building an irrigation system in Bolivia and constructing an organic microbrewery and bakery project in Monterrey, Mexico. About 20 percent of Global Resolve’s students travel and work abroad as part of their study, although funding issues sometimes complicate the opportunity for others. The focus is on teaching students to listen, connect with and to establish trust with their clients, said Mark Henderson, the professor who leads Global Resolve. Some graduating students are going on to create their own nonprofits, while others follow more traditional career paths and work for large engineering companies. Paul Violette regularly encounters young engineers excited for their first job overseas through his work as the director of climate change and urban services with AECOM International Development, the architecture, design, engineering and construction company with an extensive international presence. He recommended that they first work to sharpen their skills and areas of focus. "I think that having a specific technical focus, whether it is health or education or the environment or whatever, really, is good for young people,” Violette said. “There are many generalists and to get an overseas assignment, to do something with any technical consequence, specialization is important." Global integration There have been some challenges integrating a global dimension into engineering education, said Petter Matthews, executive director of the London-based Engineers Against Poverty, which has focused on the issue of global development, engineering and higher education. “Principally engineering staff did not feel sufficiently confident to talk about the dimensions of global development, like climate change,” said Matthews, referring to a study conducted by the Institute of Education at University College London on this issue. “So there were good academics and engineers but they felt they were going beyond their realm of knowledge if they were teaching students some of these new factors,” he said “The second part was that the curriculum was already too full, and it was not possible to fit in additional things.” Some developing countries faced unique barriers. The consortium Africa-U.K. Engineering for Development Partnership, found, based off of surveys conducted in South Africa, Rwanda, Mozambique, Malawi and Tanzania, that engineers “did not fit the industrial needs for companies based there,” according to Matthews. The consortium includes the U.K.-based Royal Academy of Engineering and Institution of Civil Engineers, Engineers Against Poverty and the Africa Engineering Forum. Sub-Saharan African companies and universities were also under-resourced and using outdated methodologies. The consortium now offers an exchange program in sub-Saharan Africa, in which academic staff from the region works in the industry abroad for up to two months to upgrade their skills. Matthews agreed that engineers coming from developed countries with the aim of working in the global South need to hone their softer skills. “The cultural sensitivity, the building quality relationships, emphasizing communication, those things need to be there,” he said. “In some ways those soft skills were not valued at one time and are now seen more commercially.” Considering the implications of climate change and its effects on different regions is key, he said. He added that global engineers need to have a strong sense of integrity, as they could encounter situations involving corrupt actors or dynamics. Leslie, of Engineers Without Borders, noted that there is “room for everybody” and that strengthening local capacity at the government and academic level is indeed important. She noted that a lot of international, for-profit companies enter developing countries and execute projects that wind up being divorced from the communities. Those interested in becoming global engineers consider programs that would enable them to work across cultures and time zones, she said. “In order to do this work you have to have a kind of understanding of what and who you are and you have to have a global perspective of different time zones and environments and to be able to recognize that you have to be able to prioritize and be an advocate for your community,” she said. Most importantly, she recommended recent grads simply work as engineers — ideally on their home turf, to familiarize themselves with the basics of the work. James Mihelcic, the director of the master’s international program in civil and environmental engineering at University of South Florida, said that in addition to some of these “soft” or “power” skills, he recommends emerging global engineers walk into the field armed with a second language. “There’s a question of how do you assess local cultural factors, like gender, that might impact your solution,” he said. “Then you can talk teamwork, dynamic group skills. These are really important areas that have been overlooked.” You know you need a postgraduate degree to advance in a global development career, but deciding on a program, degree and specialization can be overwhelming. In partnership with APSIA, Duke Center for International Development and the MPA/ID Program at the Harvard Kennedy School, we are digging into all things graduate school and global development in a weeklong series called Grad School Week. Join online events and read more advice on pursuing a post-graduate education here.

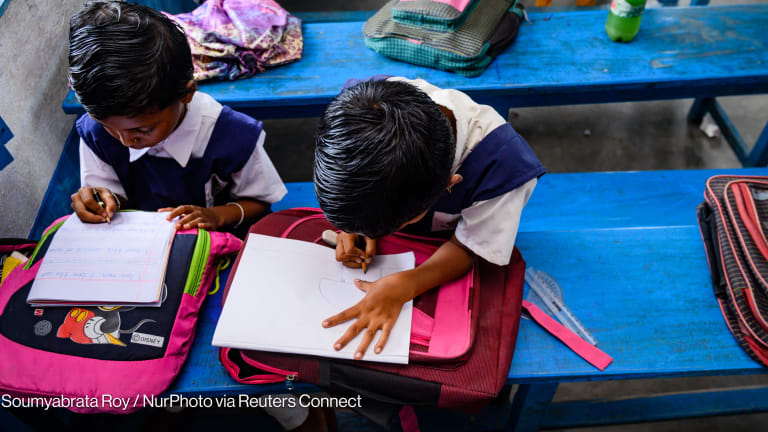

Traditional engineering courses are becoming increasingly varied as universities and major firms alike recognize the need to cater to the needs of a quickly globalizing world.

“The field of engineering is changing. It’s no longer focused on the local type of engineering — it’s more global talk, global engineering, and the key is, how do we create global engineers?” said Bernard Amadei, the founder of Engineers Without Borders and former director of the Mortenson Center in Engineering for Developing Communities at Colorado University Boulder. “You ask engineering students today why they are interested in the degree and they say they want a meaningful education and careers.”

The Mortenson Center in Engineering for Developing Communities, founded in the early 2000s, is one of the engineering programs that has popped up within the past 10 years to prepare engineering students to work in developing countries. The work requires students to dramatically broaden their skill set and frame of mind.

This story is forDevex Promembers

Unlock this story now with a 15-day free trial of Devex Pro.

With a Devex Pro subscription you'll get access to deeper analysis and exclusive insights from our reporters and analysts.

Start my free trialRequest a group subscription Printing articles to share with others is a breach of our terms and conditions and copyright policy. Please use the sharing options on the left side of the article. Devex Pro members may share up to 10 articles per month using the Pro share tool ( ).

Amy Lieberman is the U.N. Correspondent for Devex. She covers the United Nations and reports on global development and politics. Amy previously worked as a freelance reporter, covering the environment, human rights, immigration, and health across the U.S. and in more than 10 countries, including Colombia, Mexico, Nepal, and Cambodia. Her coverage has appeared in the Guardian, the Atlantic, Slate, and the Los Angeles Times. A native New Yorker, Amy received her master’s degree in politics and government from Columbia’s School of Journalism.