Can climate adaptation attract private capital? COP30 delegates think so

A surge of optimism around adaptation investment is sweeping COP — but experts say the numbers don’t add up.

For years, finance aimed at helping communities reduce the risks and harm they might suffer from climate disasters — known as adaptation finance — has been treated as the unglamorous poor cousin of mitigation finance: Necessary to have, but impossible to monetize. At the climate conference COP30 this year, that narrative has flipped almost overnight. Country delegates, financiers, and development agencies are suddenly talking with confidence about the investability of climate adaptation, pointing to new finance vehicles and blended structures that promise to draw in vast amounts of private capital from corporations and impact investors. This week in Belém, Brazil, nations are negotiating a potential new adaptation finance goal that could triple the annual amount to $120 billion if developing nations get their way. But many experts say this is nowhere near what’s needed: A report last week estimated that strengthening adaptation and resilience will cost $400 billion annually. Climate adaptation has long struggled to attract funding — particularly from private sector investors — because its benefits are local, long-term, and hard to quantify. Projects are not meant to bring direct financial returns, but to benefit people and develop safe infrastructure. But amid record heat and a rise in devastating floods and droughts, along with sea-level rise, adaptation is increasingly viewed not only as a humanitarian imperative, but as a critical pillar of sustainable development and global economic stability. “This COP needs to be about how scarce public resources can unlock private finance,” Patrick Verkooijen, the CEO of the Global Center on Adaptation, told Devex. “That’s the bottom line. Public finance isn’t there; we have big gaps, so how are we going to fill them? Guarantee systems and PPPs,” or public-private partnerships. Blended finance and insurance-linked products can also attract private investors by offering predictable returns, according to a United Nations Environment Program report. Climate adaptation investments and interventions help people, economies, and infrastructure cope with the unavoidable impacts of a warming world. Unlike mitigation — which focuses on cutting greenhouse gas emissions — adaptation is about reducing communities’ vulnerability: Building flood-resistant roads, developing climate-tolerant crops, expanding early-warning systems, safeguarding water supplies, and strengthening health systems stressed by extreme heat and new disease patterns. “Adaptation has often been perceived as only amenable to public finance, and that is inaccurate,” said Ali Mohamed, Kenya’s special envoy for climate change and lead negotiator for the African Group at COP29 last year in Baku, Azerbaijan. “There is enough room for the private sector to invest,” he said. “It cannot be all public financing because it is unlikely that we’ll get the tripling. Therefore, we must be amenable and available to invite other sources of financing.” Speaking the private sector’s language The private sector is “finally waking up to adaptation,” according to Tom Beloe, director of the U.N. Development Programme’s sustainable finance hub. Advocates of adaptation are getting better at “speaking the private sector’s language” by linking it to spaces where big business may already work: food systems, agriculture, and supply chains. But behind this buzz, experts say, governments need to be realistic. Most adaptation projects struggle to produce the reliable revenue streams, low-risk profiles, or returns that private investors require. “The private sector does have a role to play in adaptation,” David Nicholson, chief climate officer at Mercy Corps, told Devex. “But what we’ve seen in the last few years, partly because of this growing gap between public finance and total finance needs, is an overcorrection,” he said, referencing a newfound reliance on the private sector to back adaptation investment. “It’s within the interest of lots of governments to exaggerate the potential of the private sector,” he said, pointing to what he called “nonsense” claims of $1 in public spending leveraging $10 to $20 in returns. Between 15% and 20% of total adaptation needed worldwide could reasonably be privately financed, according to research by the Zurich Climate Resilience Alliance Programme, a coalition of humanitarian, research, and private-sector groups. At the moment, that figure sits at about 3%. “Adaptation avoids financial losses,” Debbie Hillier, head of the Zurich Climate Resilience Alliance Programme at Mercy Corps, told Devex. “So if you’re a government, the economic case is clear and adaptation makes sense. But if you’re a private sector company, why would you pay for what is essentially a public good?” So far, private-sector interest in adaptation is coalescing around three main approaches, said Gill Lofts, EY’s global financial services sustainable finance leader. Investors are setting clearer climate or sustainability targets that carve out space for adaptation finance. They’re also experimenting with new financial products — such as specific types of insurance, loans, and bonds — that can turn resilience into a measurable, investable outcome. And firms are looking for easier ways to use capital by joining partnerships, directing funding toward specific regions or resilience goals. Long term, the private sector can benefit from the loss-avoidance aspect of investing in resilience and adaptation, experts said. In some cases, it also expands new markets for resilience-focused financial products and services in countries with fewer climate disasters to deal with. Tripling the doubling Discussions on adaptation at COP30 are happening under the banner of the Global Goal on Adaptation, or GGA, which includes a list of indicators to measure adaptation as well as the potential tripling of the annual finance goal to $120 billion. This is the first time GGA has been on the official COP agenda. The tripling of the annual goal stems from a figure decided in 2021 during COP26, where nations agreed to increase adaptation finance from $20 billion annually to $40 billion. Many low- to middle-income nations say it’s nowhere near enough. But whether a new official adaptation finance goal is set at all — and the exact figure— is expected to be decided by Friday when COP30 ends. Negotiations are taking place behind closed doors. So far, several coalitions of low- to middle-income nations support the $120 billion figure, including the Least Developed Countries, African Group of Negotiators, Alliance of Small Island States, and Arab Group. Most higher-income countries have kept quiet publicly, but European Union representatives told Hillier and Nicholson that they support adaptation finance. In general, this climate COP is largely distancing itself from finance. Negotiations about the provision of all kinds of climate finance from high-income to low- and middle-income countries were pushed into consultations rather than the main agenda, which means they are operating on a secondary stream of talks. So far, high-income countries have avoided putting any numbers on the table. This could pose trouble for Brazil, as COP30 president, in the final hours. On Friday, Jennifer Morgan, former state secretary and special envoy for international climate action at the German foreign office, posted a video on BlueSky saying, “a goal without finance is not enough,” in reference to GGA. What can the private sector reasonably do? Realistically, Hillier said, businesses can adapt and diversify their supply chains for climate pressures; build climate-resilient warehouses, ports, or transport routes; invest in climate analytics; or support resilience for their suppliers. “They need to invest in that,” said Hillier. “That’s a no-brainer — it will pay back.” Financing for big projects such as a sea wall in Ghana, she added, is less likely to be attractive to the private sector, as public goods often don’t provide financial returns. But adaptation can also be “investable” through avoiding losses. For example, design choices, such as making jetties higher to account for sea-level change or anchoring solar panels deeper in the ground to prevent damage during high windstorms, can make a big difference, according to Philippe Valahu, CEO of the Private Infrastructure Development Group, a development finance group that mobilizes private investment to build infrastructure in frontier and emerging markets — mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. “People are getting a little smarter and realizing that it pays off to pay a little more on the front end,” Valahu said. These types of investments are still perceived as risky, however. “We’re proving through our own 20 years that our losses are considerably lower than you would expect,” he said. “Our recovery rates are higher than in Europe.” A World Resources Institute analysis of 320 adaptation projects across sectors — including agriculture, water, health, and infrastructure — found that such investments can yield average returns of about 27%, with benefits arising even when disasters don’t happen. That includes productivity gains, job creation, and improved health. “Companies are realizing that climate adaptation isn’t philanthropy — it’s risk management,” Marcos Neto, assistant administrator and director for the U.N. Bureau for Policy and Programme Support, told Devex. “If your supply chain, workforce, and infrastructure aren’t resilient, neither is your business model.” Believing it now that they see it The sudden interest in adaptation finance, experts told Devex, is largely due to the increase in frequency and intensity of climate shocks in recent years. Experts said that the cost of inaction has become more expensive than the cost of adaptation. Rising insurance premiums, more frequent business interruptions, and asset losses are forcing companies to rethink their exposure. “The impacts and the frequency are increasing, as well as the intensity and variance,” said Mohamed, the Kenyan special envoy. “This impacts our economies and our lives.”

For years, finance aimed at helping communities reduce the risks and harm they might suffer from climate disasters — known as adaptation finance — has been treated as the unglamorous poor cousin of mitigation finance: Necessary to have, but impossible to monetize.

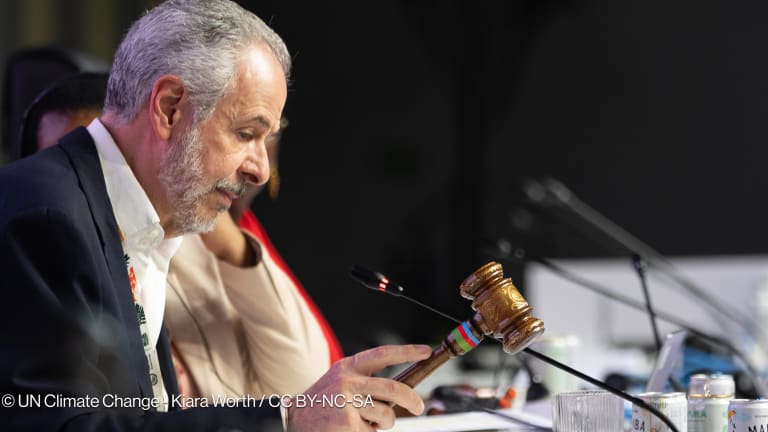

At the climate conference COP30 this year, that narrative has flipped almost overnight. Country delegates, financiers, and development agencies are suddenly talking with confidence about the investability of climate adaptation, pointing to new finance vehicles and blended structures that promise to draw in vast amounts of private capital from corporations and impact investors.

This week in Belém, Brazil, nations are negotiating a potential new adaptation finance goal that could triple the annual amount to $120 billion if developing nations get their way. But many experts say this is nowhere near what’s needed: A report last week estimated that strengthening adaptation and resilience will cost $400 billion annually.

This article is free to read - just register or sign in

Access news, newsletters, events and more.

Join usSign inPrinting articles to share with others is a breach of our terms and conditions and copyright policy. Please use the sharing options on the left side of the article. Devex Pro members may share up to 10 articles per month using the Pro share tool ( ).

Jesse Chase-Lubitz covers climate change and multilateral development banks for Devex. She previously worked at Nature Magazine, where she received a Pulitzer grant for an investigation into land reclamation. She has written for outlets such as Al Jazeera, Bloomberg, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, and The Japan Times, among others. Jesse holds a master’s degree in Environmental Policy and Regulation from the London School of Economics.