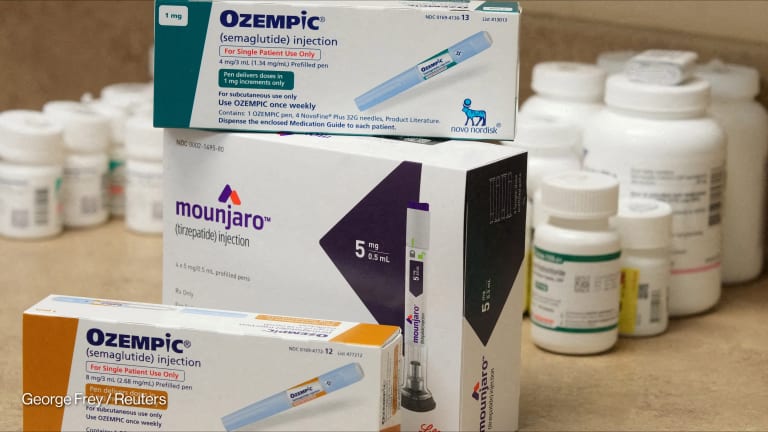

Medications such as Ozempic and Wegovy are enjoying a moment in the spotlight — largely thanks to online speculation over which celebrities might be taking them to lose weight. But they were recently singled out for another reason: inclusion on the World Health Organization’s Essential Medicines List.

Three United States doctors and a researcher submitted an application in March to include a class of anti-obesity drugs, known as GLP-1 receptor agonists, on the list, which holds outsized weight in helping governments determine which treatments they should make available to their citizens.

Experts said their inclusion could catalyze a transformation in how low- and middle-income countries recognize and respond to obesity and the noncommunicable diseases to which it contributes.