Devex Pro Insider: Is Zipline the future of US global health assistance?

This is a free version of Devex Pro Insider from Senior Reporter Michael Igoe. Usually reserved for Pro members, we’re opening it up to all readers this week as a preview of what you’re missing. This limited-edition newsletter tackles some of the biggest questions about the future of U.S. foreign aid. Not yet a Devex Pro member? Get full access to our Pro newsletters, exclusive events, and expert analysis with a 15-day free trial of Devex Pro.

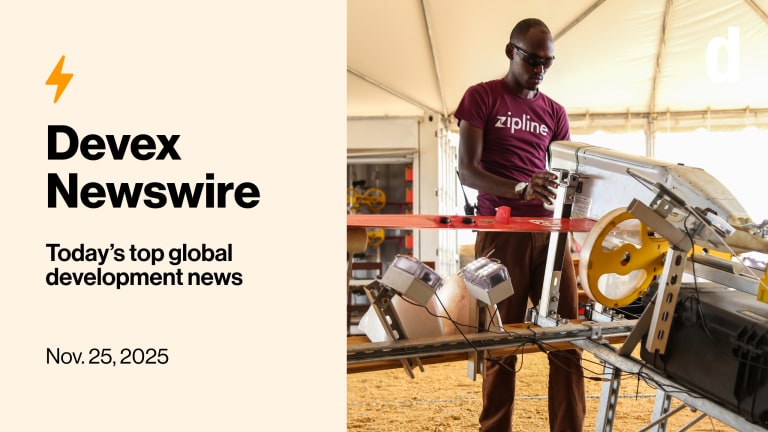

You probably saw the news last week about the State Department’s $150 million grant to Zipline, which could triple the U.S. robotics company’s global health drone operations in Africa.

Given the scarcity of information about what U.S. foreign aid will look like under the State Department’s control, the significance of this announcement seems to eclipse its dollar value.

Search for articles

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5