It is often said that digital technology will be a game changer in many areas of global development — and health care is no different.

On the ground it can help make the implementation of care more efficient and affordable. In the ether it can help bridge the information gap: the data collected can be disseminated to those working within the health system, including managers and policymakers, making it easier to monitor whether programs are progressing in terms of the prevalence of a disease, and what needs to change to improve treatment and prevention.

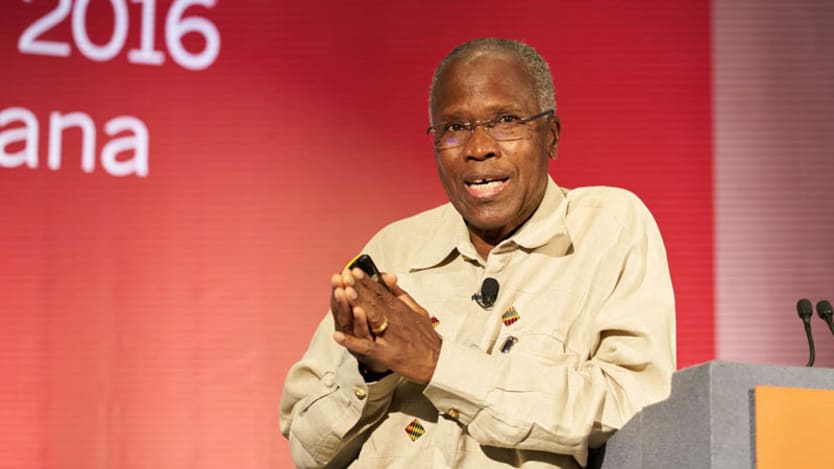

But beyond the current application of digital tech, global health actors should look for new applications that will, one day, help to improve the detection of diseases, said Dr. Peter Lamptey, president emeritus at FHI 360, in an interview with Devex Partnerships Editor Richard Jones earlier this month.

“We should not only surpass our current targets, we should be able to target new health issues,” he said.

Lamptey leads the evaluation of the community-based ComHIP project in Ghana — a partnership between FHI 360, Ghana Health Service, Novartis Foundation, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, VOTO Mobile and local partners — which aims to increase awareness, diagnosis and treatment of hypertension.

Up to 30 percent of Ghanaians living in urban areas have hypertension and is a “huge problem,” Lamptey said, adding that the proportion of people aware of their condition is extremely small; and of those who receive treatment, only about 47 percent have their hypertension controlled.

So how can digital tech have an impact in this particular context of a noncommunicable disease?

“It is always vital to do evidence-based approaches, to gather the data that shows that this program is effective, it is cost-effective, it is scalable, and it is sustainable.”

— Dr. Peter Lamptey, president emeritus, FHI 360“Once a nurse confirms hypertension, she uses telemedicine to refer patients to a district hospital,” Lamptey explained. “She ensures the data has been stored; part of the data comes to me as the researcher, part goes to the ministry [of health], and part goes to the district hospital.”

Text messages are sent to encourage people to get their blood pressure checked, and reminds them of appointments.

Lamptey shared with Devex how to form robust partnerships — such as that between FHI 360, Novartis Foundation and private sector actors — how to manage and evaluate projects efficiently, and what the future holds for digital health. Here are some highlights from that conversation:

At FHI 360, you work with a multitude of different donors and partners. How is the partnership on the ComHIP program different?

It’s not a [traditional] donor-recipient relationship. It’s very collaborative. We are partners. We bring ideas to the table together, we receive input, but more importantly we share the same ideas in terms of how this can make a difference.

The funding is not as much as, say, [the United States Agency for International Development] or the [Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation], but it is targeted to solve a problem and, in this case, the huge problem of hypertension. Despite the fact that noncommunicable diseases are bigger than most of the other health problems combined, there are very few donors active in this area. So I think this will go a long way to help address a problem that's been neglected for years.

From your experience in providing technical and strategic leadership for FHI 360's public and development programs, what's been the standout achievement here in Ghana, and what aspects have been genuinely innovative?

This partnership is bringing innovative solutions to several community-based programs; approaches that have never been used before. Having private sector drug outlets or community nurses screen people for hypertension, to [or having people] be treated by nurses in their community; having drugs dispensed not in the high-level pharmacists, but by other drug outlets; working in collaboration with the Ghana Health Service and other partners in the country to test this new approach — if it works it will revolutionize not only hypertension management in Ghana, but in a lot of other lower-middle-income countries and I think it can be scaled up.

What obstacles have you had to overcome while implementing this project and what solutions have worked in practice?

There have been several challenges. Fortunately, the broad partnership has worked very well, but the first challenge [was] simply getting [agreement] to do the task: shifting from doctors, to nurses and to drug outlets, until everybody around the table said, “Yes, the current system doesn't work, why don't we give this a try.”

The second challenge is trying to convince the community members — clients and potential clients who often don’t have symptoms — to get screened. Within our partnership we’ve evolved a lot of community-based education programs. And that has changed things dramatically, increasing from 10-20 percent of people enrolling in the program after they've been screened, to 74 percent over the last six months.

The third challenge has been the community's acceptance of the program — which is again critical. This is not something we are bringing to them. This is something we are doing with them.

The fourth challenge would be reducing out of pocket expenses to the individual. You have a disease that most people are going to be treating for the next 30 or 40 years, and if they have to spend a lot of money, even a fraction of their salaries, this is not sustainable. So we're working with a national health insurance agency to make sure the cost of the drugs is [covered].

And by doing it in the [local] community you also reduce an important component of out of pocket expenses: transportation and loss of revenue. If you take 10 minutes to get screened it’s better than taking four hours to go to a health facility.

What advice do you have based on your experience on this project? What can global health practitioners really take away from ComHIP blood pressure interventions?

It is always vital to do evidence-based approaches, to gather the data that shows that this program is effective, it is cost-effective, it is scalable, and it is sustainable.

Secondly, even if the amount of money is relatively small, a well-designed program can be a successful and innovative [model] for other people to pick up on.

There isn't a lot of funding for a NCDs, so the fact that we are bringing an affordable program means that the governments themselves, and the communities, can take this model and be able to use it without a massive amount of funding from our side. Of course a lot of funding would be useful, but this shows that at least national governments can start intervening without having to wait for external donors.

In terms of the sustainability of the projects you touched on a couple of elements there. How important is financial sustainability to a project like this as you transition from pilot to scale?

Without considerations of sustainability, programs like this are virtually useless. The key is that the community be part of it; if they want it they will be responsive to all the elements.

The combination of the private sector, the community and the fact the whole program is affordable is likely to make it more sustainable in the long run, and also on a large scale. And those elements cannot be underestimated here.

As a physician yourself, what is your prognosis about the future sustainability of the project?

We are going to change the acceptance of hypertension in the community. People are going to recognize that it is a serious health problem even though they don't have any symptoms. They are going to see that they have the power to make the difference in terms of changing their own individual behavior, but also taking medication if they have hypertension.

This is not a physician-based problem. This is their problem; they are the ones who can solve it and they are the ones who can benefit from the success.

As an evaluator, I would like to see compliance rate and control rates of hypertension go through the roof. I'm very confident that this will be the case.

Devex Partnerships Editor Richard Jones contributed reporting.

Wired for Impact is an online conversation with Novartis Foundation and Devex to explore how to integrate digital health into global development in a way that is scalable and sustainable, and improves the overall quality of health care delivery to build essential connections between patients, health facilities, health providers and policymakers. Tag #Wired4Impact and @Devex to join the conversation.

Search for articles

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5