Does BRAC offer a different model for development organizations?

Founded a half a century ago in Bangladesh, BRAC now operates in 10 countries in Africa and Asia. Could its approach be a model for other development organizations? We spoke to BRAC International Executive Director Shameran Abed to find out.

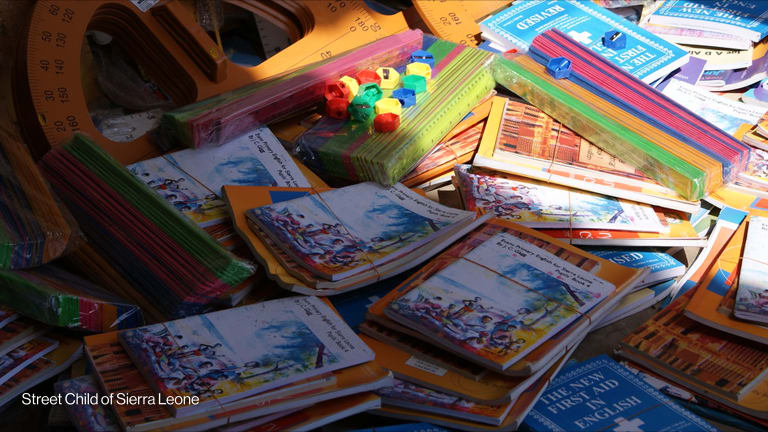

Near the end of 2001, after American troops toppled the Taliban-led government in Afghanistan, the leaders of BRAC were hearing familiar stories. Afghanistan had seen its infrastructure destroyed. The education system was in tatters. The economy had collapsed with people struggling to provide for their livelihoods. Meanwhile, scores of refugees were returning to the country following the end of the war. BRAC had responded to similar conditions in its native Bangladesh when it was formed in 1972. At the time, the country was emerging from a liberation war that had forced millions to flee. Fazle Abed, a British-educated naval architect and accountant who until that point had worked in the private sector, returned home and built BRAC — then short for Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee. The organization’s leadership thought that they could replicate the work the organization now known simply as BRAC had done in Bangladesh, which had already turned it into one of the largest NGOs in the world — by some measures the largest — and one of the very few INGOs based in the global south. They would provide the expertise garnered by rebuilding education systems and health structures and helping to provide financial services for people in postwar Afghanistan as BRAC did in Bangladesh. The work in Afghanistan was a big turning point, said Shameran Abed, the executive director of BRAC International, the unit that manages foreign operations. It suggested to BRAC that its model could be tested elsewhere and potentially deliver similar development to other parts of the world. The organizations’ thinking at the time was “Why don't we try it out and see how we do?” Abed said. “That was kind of it,” he went on. “So it didn't happen out of many years of planning for international growth. It was kind of something that happened. And there we were.” It’s been more than two decades since BRAC’s foray into Afghanistan. In addition to its original presence in Bangladesh, the organization now operates in 10 countries across Africa and Asia. Abed said that over the next decade, he hopes BRAC will grow to be in 18 to 20 countries. “We'd like to go much deeper in most of the countries where we operate,” he said. “We want to be as if we are there and we are local … reach very vulnerable people, deeply rural, in most of the countries where we operate.” A story of growth BRAC grew from modest beginnings, financed by revenue from the sale of its founder’s apartment in London in the 1970s. At first, the organization operated like a traditional charity — providing health services, starting schools, and giving food — but quickly, it moved to a business-based model. BRAC started by acquiring a printing press to supply textbooks for schools which generated an income for the organization. Meanwhile, the business hired people in the community, creating much-needed jobs in the process. The printing press soon proved to be profitable and BRAC saw a trick that could be replicated across the country. So it created social enterprises — businesses whose goal is to serve social needs — that ranged from microfinance institutions to retail stores, to a dairy company and a seed company, all of which generated revenue for BRAC that was reinvested to fund its social programs. BRAC grew fast and nowadays employs thousands of people serving tens of millions. Abed told Devex that his organization’s growth is rooted in the idea that whatever they are trying to do, they do it big. “Our theory of change is a relentless pursuit of scale,” he said. “We don't want to do things small. We don't want to do things on the edges, and we don’t want to do things that look good, that are impactful, but only in very small doses and can’t be scaled. We will compromise a little bit on the beauty of something, the perfection of something, to be able to scale so that many people can benefit.” The organization deploys a strategy built on growing social enterprises to both get communities onto the path of development and also generate revenue, at the same time. It’s not just enough, for example, to give someone a loan to finance a business, Abed said. For a pastoralist, getting money to buy cows is a start. But they need to find a cow to buy. When they’ve bought the cow, that cow will then need to be vaccinated to protect it from diseases. When it starts giving milk, the pastoralist will need a market to start selling the product. This chain of needs proved crucial to how BRAC approached its work. “What BRAC realized was that to solve problems for poor people, you need to have a whole bunch of things that you need to do, and you need to do it in a way that's, as much as possible, holistic and integrated,” Abed said. So they scaled that model to other areas of the rural economy, focusing on women, who Abed said were key to economic development. Abed explained that when they started working in rural areas, they saw that women in those communities for example had skills for handicrafts but struggled to get their products to the market. So they decided to solve this gap by opening up retail stores, known as Aarong, to help them get their products to markets in urban areas. BRAC also decided to work with designers who developed ideas that the women would embroider on handicrafts that they would then sell at BRAC’s stores, linking city designers to rural creators who can then sell back those designs in urban markets. Those stores now sell products that include dresses and men’s suits, and BRAC has set up an e-commerce platform to sell outside Bangladesh. “So we've created this entire value chain. We take the skills that are there and provide and link that to the market, right? And through that, we are providing livelihoods for 80,000 artisans sitting across all of Bangladesh,” Abed said. To Abed, this mix of profit and purpose is essential. “You can't have social development without economic empowerment and you can’t have economic empowerment without social development. I mean, one doesn't quite work without the other,” he said. This approach has built a self-sustaining model for how BRAC funds its development work, Abed said. In addition to its many social enterprises, BRAC is the largest shareholder of BRAC Bank, a lender to small- and medium-sized enterprises, which it started in 2001, and which garners its regular dividends. The organization also earns revenues from other investments and returns from the microfinancing business. These businesses fund about 80% of the organization’s budget, with the rest coming from donors. “For us, that model has worked very well,” Abed said. Local gone global Abed feels BRAC’s growth into a sprawling multinational can provide a blueprint for other development organizations. “BRAC Bangladesh is the greatest success story of a local organization and if I was wanting a local organization somewhere, this would be the playbook,” he told Devex. He said local organizations were being sold short if they rely on foreign organizations as a channel to access donor funds. An organization “can build its own donor relationships, it can prove to donors that it can do programming at high quality at scale, do proper grants management and have high amounts of credibility with the donor,” Abed said. BRAC has illustrated this point, he said. It has even won five-year unrestricted funding from some bilateral donors. Building from the ground up Abed said debates over localization need to go beyond where an organization comes from, where it’s based, or where it’s founded and headquartered. “The issue is — are we working with local communities and solving problems locally right now,” he said. Now BRAC is an INGO, working with local organizations, and it is trying to stay true to its local roots. Through its international work, whether in Uganda, Tanzania, Liberia, Sierra Leone, or Rwanda, BRAC builds out its work from the ground up, Abed said. “We are trying to be that large-scale, very close to the ground implementer, so even if we’re not a Rwanda organization we want to have a large-scale local presence,” he told Devex. BRAC will choose to have implementers who are steeped in the rural communities they are serving. “Where we might not be considered local, we actually are a lot more local in the way we operate them,” Abed insisted. Asked how BRAC retains its original ethos it began with 50 years ago, Abed said that was one of the challenges the organization grapples with as it looks to grow over the next decade. Key to success would be ensuring that communities are “active participants” in development and women are at the center of economic power, Abed said. One other big idea for Abed is that BRAC continues to do things at scale and learn by doing and never fear failure. To do this, BRAC must be proactive in identifying solutions, he said. “The traditional development culture, which is that you become very reactive to donors and you just keep responding to donor calls, you get money, you deliver programs, you keep the donor happy, they give you more money,” Abed said. “What we want to do is not be reactive to what the donor wants, but be reactive to what the communities need.” Update, July 21, 2023: This article has been updated to clarify that BRAC has already set up an e-commerce platform to sell outside Bangladesh.

Near the end of 2001, after American troops toppled the Taliban-led government in Afghanistan, the leaders of BRAC were hearing familiar stories.

Afghanistan had seen its infrastructure destroyed. The education system was in tatters. The economy had collapsed with people struggling to provide for their livelihoods. Meanwhile, scores of refugees were returning to the country following the end of the war.

BRAC had responded to similar conditions in its native Bangladesh when it was formed in 1972. At the time, the country was emerging from a liberation war that had forced millions to flee. Fazle Abed, a British-educated naval architect and accountant who until that point had worked in the private sector, returned home and built BRAC — then short for Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee.

This story is forDevex Promembers

Unlock this story now with a 15-day free trial of Devex Pro.

With a Devex Pro subscription you'll get access to deeper analysis and exclusive insights from our reporters and analysts.

Start my free trialRequest a group subscription Printing articles to share with others is a breach of our terms and conditions and copyright policy. Please use the sharing options on the left side of the article. Devex Pro members may share up to 10 articles per month using the Pro share tool ( ).

Omar Mohammed is a Foreign Aid Business Reporter based in New York. Prior to joining Devex, he was a Knight-Bagehot fellow in business and economics reporting at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. He has nearly a decade of experience as a journalist and he previously covered companies and the economies of East Africa for Reuters, Bloomberg, and Quartz.