As a medical student and then obstetrician-gynecologist resident at the turn of the millennium, Ethiopian Dr. Muir Kassa’s work was bleak. Across the country, delivery and gynecology rooms were overwhelmed with cases of women that had undergone unsafe abortions.

“Lots of women died at my hands because they attempted unsafe abortions at home, by using some unimaginable ways, like inserting umbrella wires. It becomes very difficult to save her once she already has these complications,” he said.

One story is etched in his memory — a 19-year-old woman who had a backstreet abortion in a man’s house where he removed her kidney and uterus, along with the fetus, also damaging her intestines. She survived but was left with a permanent colostomy.

“Imagine the pain she went through. It’s unbearable,” he said. “It’s barbaric.”

It was an all too common story at the time, he added, with women dying needlessly.

The horrors and helplessness of it all were almost too much to bear — he considered leaving the field of medicine. But he decided to remain in the profession and is now a senior technical adviser to the Ethiopian minister of health.

“You don't see those gruesome cases of severe morbidities and deaths [that occurred when abortion was illegal in Ethiopia]. … With safe abortion, you switch a button and you start saving lives.”

— Dr. Muir Kassa, senior technical adviser to the Ethiopian minister of health.Research conducted between 1980 and 1999 found that unsafe abortion was the highest contributor to maternal death in Ethiopia, accounting for about a third of the deaths. Meanwhile, nearly 25,000 were estimated to have died as a result between 1995 and 2000.

“At the time, doctors used to reserve around 10 beds in some of the hospitals for women who had become septic after trying an unsafe method of abortion,” said Dr. Abebe Shibru, MSI Reproductive Choices Ethiopia country director.

But the country made abortion allowable under a broader set of circumstances in 2005, and following this, lives were saved and health systems were relieved of a major burden. Now, health professionals in Ethiopia watch anxiously as a global movement to criminalize abortion gains traction, namely with the recent Supreme Court decision in the United States.

‘You switch a button and you start saving lives’

Before 2005, abortion was illegal in Ethiopia, except to save a woman’s life or prevent severe damage to her health — but health providers often weren’t familiar with exceptions to the law, and there was a high bar for approval of the procedure, requiring the signoff of two medical practitioners, including a specialist.

This didn’t stop women from having abortions, it only stopped access to safe ones. A study from the Guttmacher Institute and the World Health Organization found that the proportion of unintended pregnancies that end in abortion is as high as 68%, even in countries that prohibit the service.

“In all societies, no matter what the legal, moral, or cultural status of abortion are, there will be some women who will desperately seek to terminate an unwanted or unplanned pregnancy,” according to a 2001 study on Ethiopia, which called unsafe abortions “a major medical and public health problem” in the country.

According to a Center for Reproductive Rights report published in 2003, in Gambella Hospital in rural Ethiopia, “patients with abortion complications constituted 70% of all admissions to the gynecological ward.”

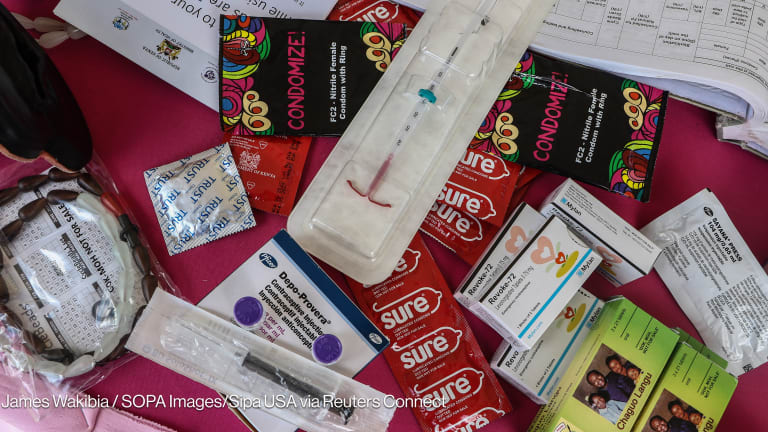

But with a push from civil society organizations, such as the Ethiopian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Ethiopian Women Lawyers Association, the government expanded the circumstances under which an abortion is allowed to include rape, incest, fetal impairment, if a woman’s life is in danger — including if she has a mental health condition — or if she is a minor who is unprepared for a child. It became a decision between the woman and her provider.

“If a woman says she was raped, she is not required to bring in a witness. Her word is enough,” Shibru said.

While unsafe abortion led to about a third of maternal deaths before the change in law, by 2016, less than 1% of maternal deaths were attributed to complications from abortion. Kassa added that before the change in the law, about half of all hospital beds in the women’s section were occupied by patients who had undergone unsafe abortion; now it's also less than 1%.

"You don't see those gruesome cases of severe morbidities and deaths,” Kassa said, adding that safe abortion is also the cheapest way to save women’s lives — other efforts require much more extensive investments. Often it’s now performed using medications — which wasn’t happening in the past. "With safe abortion, you switch a button and you start saving lives.”

The most significant barrier to access that still remains is when health workers deny women abortions, even though they include one of the exceptions, because of their own beliefs, Kassa said. But the government has training efforts or “value clarification exercises” to prevent this from happening.

“There is no conscientious objection in Ethiopian law,” he said.

‘We’ve come a long, long way’

Ethiopia’s experience echoes what happened in Nepal, which expanded abortion access in 2002. Before this, over half of maternal deaths in major hospitals were attributed to unsafe abortions.

The must-read weekly newsletter for exclusive global health news and insider insights.

Before the change in the law, “sometimes clients came into the clinic after being advised by traditional providers to use a four-centimeter-long ‘medicinal stick’ that was inserted in their vaginas,” said Lila, a midwife.

Sobha, a nurse, remembers a girl that committed suicide after denial of an abortion. The organization they currently work for, MSI Reproductive Choices, asked that their last name be withheld to respect their privacy.

“After legalization, we have seen a sharp decline in maternal mortality,” said Tushar Niroula, executive director of MSI Reproductive Choices Nepal.

Even so, there are barriers to access. The country has a rough, mountainous terrain, and transportation is not always available to health facilities. There are also not enough medicines, equipment, or trained health workers.

Other parts of the world have experienced similar stories. Since abortion was legalized in Mexico City in 2007, there has been an 80% reduction in abortion-related emergency cases and there have been no abortion-related deaths.

‘We will not go back’

Younger health care providers in Ethiopia may have never witnessed a woman die at their hands from an unsafe abortion as Kassa did — and he wants to keep it that way.

“They don't even know the damage it caused. You have to ask an older physician to understand this,” he said.

Instead of dying or living with lifelong disabilities, women are continuing their education and contributing to the nation’s economy.

"It empowers a woman and it also empowers the country,” he said.

But in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade, which enshrined the constitutional right to abortion, there is concern other countries might follow suit.

“Some people here are emboldened and they try to change the law,” Kassa said, adding that there are groups within the country that work in tandem with well-funded American, far-right religious organizations.

Evangelical anti-abortion push influencing UK position, say activists

After the U.K. government weakened the language protecting sexual and reproductive rights in a conference statement, campaigners are concerned tactics that caused a rollback of abortion protections in the U.S. are being employed in the country.

And people globally are watching what is happening in the U.S. closely. Kassa said the recent move by Kansas voters to keep abortion legal is a good sign. He doesn't see a foreseeable change in Ethiopia because there is broad-based support for the law, but health professionals are “watching cautiously” what is happening overseas.

“The U.S. has lots of influence — directly or indirectly — on Ethiopia and other African countries,” Kassa said.

And this influence has deep roots. When Ethiopia was working to broaden access to abortion two decades ago, the U.S. played an outsized role in stifling discussion.

The so-called global gag rule — which prohibits organizations from receiving U.S. foreign aid to provide abortion services — “was making it harder to dispel myths about abortion and accurately inform the public about the positive impact of liberal abortion laws,” according to the 2003 Center for Reproductive Rights report. This was at a time when the former U.S. President George W. Bush’s administration decided to reinstate the rule.

“We talk in hiding, whispering to each other. This will continue until the global gag rule is ended or we have other means of funds,” said an Ethiopian government official at the time.

Against the backdrop of the most recent abortion decision out of the U.S., MSI Ethiopia’s Shibru said: “We must be clear: We will not go back to how things were.”