How a new $100B green energy alliance will work

A new philanthropic-led green energy alliance shows how the philanthropic and corporate sectors are trying to take the lead amid uncertainty about government commitments to addressing climate change in the global south.

Advocates for renewable energy and addressing climate change are applauding a new renewable energy alliance between a trio of philanthropic mega-donors — Bezos Earth Fund, IKEA Foundation, and The Rockefeller Foundation — and financial institutions, saying it could be instrumental in speeding up the development of technologies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But the ambitious initiative also could face challenges as it gears up for quick action and works to implement accountability measures. The Global Energy Alliance for People and Planet was launched last week during COP 26. According to a press release, the initiative is launching with $10 billion but wants to “unlock $100 billion in public and private capital” to address three areas: reaching 1 billion people with renewable energy, averting 4 billion tons of carbon emissions, and creating or improving 150 million jobs. It is focused on the global south. An analysis published by the alliance said that while “energy-poor” countries — including those in Africa, Asia, and Latin America — were currently responsible for just 25% of global carbon dioxide emissions, their share could grow to 75% by 2050 if they aren’t part of the transition to green energy. “The world is undergoing an economic upheaval, in which the poorest are falling farther behind and being battered by climate change’s effects,” Dr. Rajiv Shah, president at The Rockefeller Foundation, said in a statement announcing the alliance. “Green energy transitions with renewable electrification are the only way to restart economic progress for all while at the same time stopping the climate crisis.” The alliance builds on a $1 billion partnership that IKEA Foundation and The Rockefeller Foundation announced earlier this year to spur renewable energy investments. The expanded initiative now includes money from the Bezos Earth Fund and is meant to encourage additional capital investments from development finance institutions and multilateral banks attached to the initiative. Investment partners for the alliance include the African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, European Investment Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, International Finance Corporation, U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, the World Bank, and the United Kingdom’s CDC Group. IKEA Foundation CEO Per Heggenes told Devex that a benefit of the blended funding model is that philanthropic funding for energy projects in the countries where the foundations operate would potentially make the projects more attractive and less risky for banks and financial institutions. “If we can de-risk investments, more financial resources will come from the development banks and maybe from the private sector because the global south is a more risky area to invest in,” he said. One of the alliance’s goals is to speed up replacement of diesel generators and coal-fired power plants with renewable alternatives worldwide. That will be done by developing mechanisms to encourage and accelerate the decommission or repurposing of aging coal plants before the end of their economic lives, as well as large installed diesel/heavy fuel oil assets, an IKEA Foundation spokesperson told Devex. “Once you see that you can’t rely on politics to solve a problem, other sectors step up.” --— Deb Markowitz, vice president and state director, Nature Conservancy’s Massachusetts office Big investments for big climate goals Jennifer Layke, global director of the energy program at World Resources Institute, said the alliance is tackling a “pretty critical issue” by trying to direct more investment toward innovative technologies. “I think the value of a philanthropic effort like this is that it creates the pathway for investors to feel that they can have confidence in the context in which they’re making that kind of newer, innovative move,” she said. She said that for years, the philanthropic community has been investing in smaller-scale activities in the development space, but this is the first time they’re saying “our big climate goals require big climate investments, big portfolios, and platforms.” She added that philanthropies can help “intermediate” the program and structure in which investors might want to enter markets in the global south. WRI is not currently involved with the alliance. But there have been preliminary discussions about how WRI might participate, Layke said. She said that one challenge for the alliance might be developing a vision while getting set up and working quickly. That might require developing multiple tracks to work on immediate priorities while establishing a long-term view for the initiative. The alliance should be in a position to talk about how they have disbursed funding, built a pipeline, and catalyzed investors to make commitments by next year’s COP, Layke said. Heggenes said he’d like to see the alliance — which will be its own separate entity — staff up quickly. “This will be set up as a separate structure 501(3)c in the United States,” he said. “So it's a not for profit structure. And it will be able to recruit people to actually run this operation as a totally separate organization, and it will not be Rockefeller or Bezos Earth Fund or IKEA running this.” While the founders will be part of the governance structure, he added, the alliance will operate as its own organization, much like Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance or Global Fund. He also said that he’d like to see it be accountable to the communities with which it will work and plans to take a “country-led” approach. “We will work with the countries that are interested in working with us,” he said. And there will be a “robust” monitoring and evaluation system to measure the alliance’s impacts and delivery on commitments, according to Heggenes. That system will help the alliance “course correct in a way if we see that certain things aren't working and we need to do it differently,” he said. Stepping in where nations — sometimes — won’t The Global Energy Alliance is significant because it shows how philanthropic organizations and corporations are stepping in at a time when climate change commitments from governments are increasingly being seen as unreliable, said Deb Markowitz, vice president and state director for the Massachusetts office of the Nature Conservancy, a global environmental organization based in the U.S. “One of the things that we’re seeing at the climate summit is that the nations are inconsistent,” she said. She highlighted the U.S. reversal on climate change following the signing of the Paris Agreement as an example. Former U.S. President Barack Obama made a “huge” announcement and came to an agreement with other major emitters such as China, India, and the European Union — only for former U.S. President Donald Trump to announce plans to back out of the deal in 2017. “Once you see that you can’t rely on politics to solve a problem, other sectors step up,” Markowitz said. The Nature Conservancy received a $100 million donation from the Bezos Earth Fund last year for work to mitigate emissions in Canada, India, and the U.S. Markowitz said she hopes philanthropies, corporations, and financial institutions continue to engage with scientists to ensure that their climate initiatives have the intended impact.

Advocates for renewable energy and addressing climate change are applauding a new renewable energy alliance between a trio of philanthropic mega-donors — Bezos Earth Fund, IKEA Foundation, and The Rockefeller Foundation — and financial institutions, saying it could be instrumental in speeding up the development of technologies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

But the ambitious initiative also could face challenges as it gears up for quick action and works to implement accountability measures.

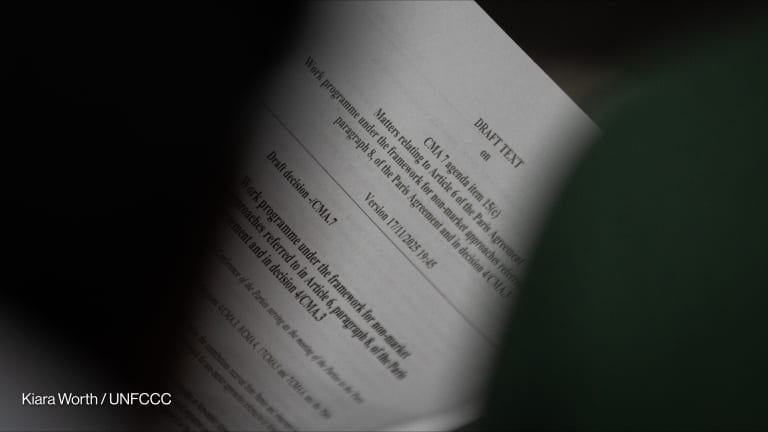

The Global Energy Alliance for People and Planet was launched last week during COP 26. According to a press release, the initiative is launching with $10 billion but wants to “unlock $100 billion in public and private capital” to address three areas: reaching 1 billion people with renewable energy, averting 4 billion tons of carbon emissions, and creating or improving 150 million jobs. It is focused on the global south.

This story is forDevex Promembers

Unlock this story now with a 15-day free trial of Devex Pro.

With a Devex Pro subscription you'll get access to deeper analysis and exclusive insights from our reporters and analysts.

Start my free trialRequest a group subscription Printing articles to share with others is a breach of our terms and conditions and copyright policy. Please use the sharing options on the left side of the article. Devex Pro members may share up to 10 articles per month using the Pro share tool ( ).

Stephanie Beasley is a Senior Reporter at Devex, where she covers global philanthropy with a focus on regulations and policy. She is an alumna of the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism and Oberlin College and has a background in Latin American studies. She previously covered transportation security at POLITICO.