NEW YORK — Women have spent more time than men performing unpaid care work during the COVID-19 pandemic, initial research suggests. But tracking how women and men divide their time between paid and unpaid work is likely to become more significant in a post-coronavirus era, pushing time use surveys — a once-uncommon form of data collection that is both expensive and time-consuming — into the spotlight, gender data experts say.

Q&A: What early data says about gendered impacts of COVID-19

UN Women rolled out surveys in multiple countries in Asia and the Pacific just weeks after the pandemic was declared. Statistics specialist Sara Duerto Valero explains how the agency was able to act so quickly, and what the data reveals so far about the impacts of the crisis on men and women.

“There is increasing interest. I imagine that with the pandemic, there is going to be more interest because it is obvious that women's unpaid work is going to become more and more important. I think that will really highlight the importance of these time use surveys,” said Mayra Buvinic, a senior fellow with Data2X.

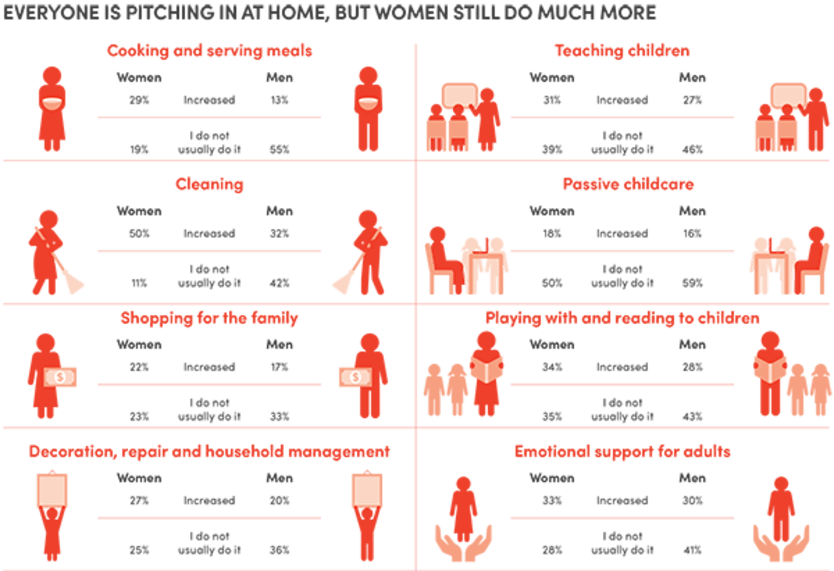

Rapid response surveys of unpaid care work over the last few months show similar results: Women spend more time than men on unpaid domestic and care work, and they have increased the amount of time spent on these tasks during the pandemic, according to UN Women.

Initial results also show that women and men are spending less time doing paid work than they did before the pandemic and are spending more time on personal care, socializing, and consuming media, according to Francesca Grum, chief of the social and gender statistics section of the United Nations Statistics Division. One unexpected trend is that men are spending more time than before on unpaid care work, Grum said.

“People are spending more time on domestic chores and taking care of the kids. That's something that we see in all the countries that have collected data. And the beauty is also that it seems that both women and men are contributing. So there is still a gender gap. Still, women are still doing the bulk of the work, but somehow men are contributing a little bit more than pre-COVID,” she said in an interview with Devex.

But the findings only offer a partial window into the granular details of the new reality for many women and men, as the overall burden of unpaid domestic care has increased. And it is not yet clear how the data might translate into action and policy change.

Countries have conducted rapid response assessments of unpaid care work during the pandemic using methods like mobile phone surveys, bypassing traditional methods of daily time use diaries.

“For statisticians, if you are quite strict, you could say, ‘How accurate is it?’” said Margarita Guerrero, a development consultant and expert on time use surveys. “For now, it is fine. It is a situation where it is better to have data that is collected and pieced together in some controlled way rather than not at all.”

Granular data

Due to expense or capacity concerns, policymakers and statisticians have historically overlooked time use surveys, a quantitative summary of how people spend time over a specific period. The surveys can reveal trends regarding unpaid household and care work, which women are disproportionately tasked with across the world. With data from 160 countries, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development showed in 2014 that women performed more than double the amount of unpaid care work each day than men in most regions of the world.

Time use surveys could be used to determine women’s unpaid contributions to a country’s gross domestic product. During a pandemic, they can reveal other important trends, like how often people are washing their hands and staying home.

“I don't think that time use surveys were the first priority for countries when they were organizing themselves in terms of statistical systems when the crisis developed,” Grum said. “But governments also quickly realized that they had to better understand what people were doing — if people were really following the guidelines in terms of social distancing, staying at home, washing their hands. For all these types of questions, they needed the time use surveys, or time use questions.”

But the traditional surveys are also costly, unstandardized, and labor-intensive, sometimes requiring translation from a written questionnaire or daily diary to a digital format that statisticians can use. Other surveys involve in-person interviews, which can influence people’s responses, Grum said. Discrepancies among surveys and low response rates to the questionnaires are also common.

“The data always says women are spending a lot more time on housework ... than men. The more interesting question is: What do you do with the data?”

— Mayra Buvinic, senior fellow, Data2X“The data is super granular. They are so disaggregated. With a traditional diary, you are asked to write about what you are doing for every 10 minutes of your day. So imagine the quantity of information that you get,” Grum said.

These traditional instruments of data collection are not practical during a crisis, Grum said. The United Nations is presently working to harmonize guidelines for time use surveys that could create more consistency in methodology from one country to another.

“We need to come up with something that is very light for these crises,” Grum said.

Practical application

Time use surveys gained prominence over the last several years, following the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals. SDG 5, which measures gender equality and women’s empowerment, calls specifically for “Time spent on unpaid domestic and care work, by sex, age and location.”

“In my mind, pre-pandemic, this is what has been pushing countries to try to get the information on time use surveys. In the MDGs [Millennium Development Goals] era, developing countries were not reporting on this data, and now there is an indicator that calls for everyone to report on that,” Guerrero said.

About 250 time use surveys have been conducted since the 1960s in 88 countries, according to Data2X’s Buvinic.

“They are becoming more prevalent as part of the statistics tools that national statistics offices do regularly. But obviously, they are expensive, they are complicated to conduct, so they are mostly much more regularly conducted in developed countries rather than in developing ones,” Buvinic said.

Once countries receive and analyze time use survey data, policy action does not always follow. The challenge is not a question of existing, quality data, she said.

“There is great data. A lot of data never gets used. And the data always says women are spending a lot more time on housework, etc., than men. The more interesting question is: What do you do with the data?” Buvinic said.

“In some countries, time use surveys have been used to direct policy, but in many others, people don’t talk about the direct impact of policy. That is going to change dramatically now with the pandemic,” she added.

Has it become too dangerous to measure violence against women?

Collecting data on gender-based violence is a sensitive endeavor under any circumstance. Devex asks experts what it looks like now — when women may be in lockdown with their abusers.

There are few examples of countries, such as Uruguay, that have implemented national care policies following time use survey data collection. Uruguay adopted the care policy in 2017, expanding services for preschool children, elderly people, and people living with disabilities. Finland is another well-known example of a country that has used its routine time use surveys to guide policies on family leave, child care, domestic services, and rural women’s employment.

Uganda released its first time use survey report on unpaid care work last year, following data collection from 2017-2018 with support from UN Women. Ugandan women spend more time on unpaid care work, averaging 7 hours, compared with men, who spend 5 hours on this per day, according to the survey. The findings also showed that 81% of surveyed women agree that it is a woman’s responsibility to take care of her home and family, while 79% of men said the same.

“Of course, like we expected, the women were doing more work around the house and men were doing less. When it comes to productive activities, the men are working more than women,” said Diana Byanjeru, a senior gender statistics officer at the Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

“We also found people were spending more time on personal care — which we found surprising — and this was for both men and women. That was the most surprising element, but women are spending less time [than men] for their own personal care.”

It is challenging to follow up on the report’s findings and to produce more data on an ongoing basis, Byanjeru said.

“We have not deliberately gone out to find the impact. It is a little too early to tell. It was a very good initiative, but [there is] not such a clear future for it. The funding to do the survey is not yet a buy-in from the government. The lasting ability of it is what has worried us,” she said.

Devex, with support from our partner UN Women, is exploring how data is being used to inform policy and advocacy to advance gender equality. Gender data is crucial to make every woman and girl count. Visit the Focus on: Gender Data page for more. Disclaimer: The views in this article do not necessarily represent the views of UN Women.