Less debt, more climate action.

In theory, green debt swaps are an idea that could kill two birds with one stone: relieve poor countries of increasingly unsustainable debt levels while ensuring that what they owe goes toward mitigating and adapting to climate change. But in practice, experts say a lot will depend on how these swaps are set up, who can access them and what conditions come attached to them.

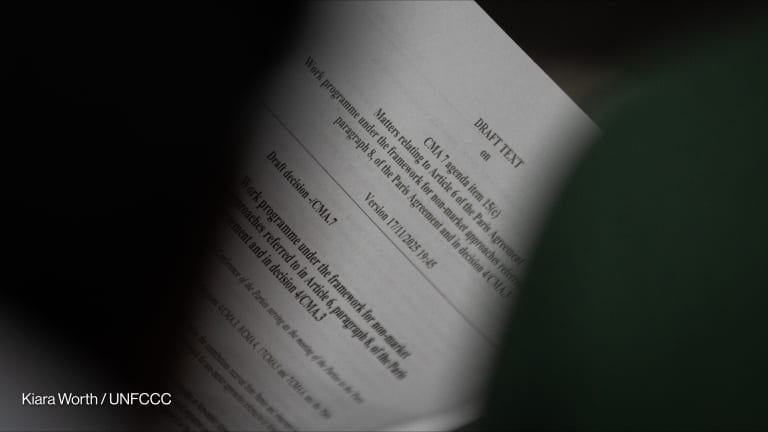

There’s growing pressure on rich countries and multilateral institutions to take action on the two issues. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank are expected to unveil a proposal for such a debt swap by November, ahead of COP 26 in Scotland.

“From a climate change perspective, this is the most important decade to mobilize trillions of dollars towards resilient economies that get us to reduce emissions,” said Kevin Gallagher, director of the Global Development Policy Center at Boston University. “Unfortunately, in this decade where we need to mobilize as much money as possible, most countries in the developing world are in debt distress.”

A problem about to burst

The African Development Bank warned in June that there is a heightened risk of debt defaults on the African continent as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to heavier debt burdens while worsening poverty and widening inequality.

A U.N.-appointed independent expert group on climate finance warned in December that 54% of low-income countries are deemed to be in debt distress or at a high risk of it.

Furthermore, a March report from the European Network on Debt and Development, or Eurodad, found that over the last five years, the share of public external debt service in government revenues in countries in the developing world nearly doubled, with governments in at least 32 countries allocating more than 20% of revenues to repay debt.

Paying back money owed outstripped health care expenditure in at least 62 countries in 2020, 25 of which are in sub-Saharan Africa, it also found.

“Unfortunately, in this decade where we need to mobilize as much money as possible, most countries in the developing world are in debt distress.”

— Kevin Gallagher, director, Boston University’s Global Development Policy CenterNo matter the situation, unpaid debts mean countries will be punished by markets making future borrowing more expensive and giving them less access to funds, said Iolanda Fresnillo, senior policy and advocacy officer on debt justice at Eurodad. This means many countries start relying more on exporting natural resources to pay back what they owe.

“Today, with increased debt levels, it’s not just that countries will keep exploiting fossil fuels to repay debt, but they have very little fiscal space to invest in climate mitigation, adaptation, and transformative models of their economies,” she said. This leads to a vicious cycle, since not having enough money to tackle climate change increases countries’ climate vulnerabilities and so do the borrowing costs, Fresnillo added.

For example, struggling with a heavy debt crisis, Mozambique offered in 2018 part of its future expected revenues from a large liquefied natural gas project to pay off its debt. Delays and security problems in the country are threatening the project, increasing the risks of a debt default.

G-20 last year offered and extended a debt suspension scheme, which allowed 47 countries to pause their repayments. But the scheme only covers loans from bilateral credits and ends at the close of this year.

Making it work

When she announced in April that the IMF will propose a green debt swap instrument, Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said it made sense to address both climate and debt crises at the same time.

The financial world has used a similar instrument before. In the 1990s, so-called debt for nature swaps used the same idea on a smaller scale: Creditors would cancel part of a low-income country’s debt in exchange for investing the savings in conservation projects.

“It’s morally wrong and economically irresponsible to ask fossil fuel exporting economies to halt exports without alternative sources of financing that can lead to a sustainable green economy.”

— Kevin Gallagher, director, Boston University’s Global Development Policy CenterThe pro, according to an assessment by the United Nations Development Programme, is that the low-income country reduces its debt obligations, and frees up spending for environmental protection. The con is that the instruments have only resulted in relatively small amounts of debt relief. Negotiations can also be time-consuming and complex, spanning several years.

Since the 1990s, the number of debt for nature swaps has decreased, but those that have recently taken shape also had a stronger climate focus. For example, Seychelles signed a swap deal in 2015, through which almost $22 million of its debt was written off in exchange for doing more to protect its oceans via marine conservation and climate adaptation programs.

Some of the most vulnerable countries today, both in terms of debt distress and climate change, are small island states, said Gallagher. The pandemic has put a strain on their budgets, while higher incidences of hurricanes devastate their coastlines and consequently, their tourism industries — a key component of government revenues.

Gallagher said the world has an “urgent opportunity” to act.

He, together with experts from other centers and think tanks that form the Debt Relief for Green and Inclusive Recovery project, released a report on Monday offering a blueprint for what green debt swaps could look like in 2021 and beyond.

They proposed that the IMF and the World Bank first perform a so-called debt sustainability analysis, determining if a given country needs debt restructuring or relief. This should take into account climate risks and spending needed to scale up investments in climate resilience.

They also suggest creating a guarantee facility that could offer assurance to a private sector that may be reluctant to invest. In exchange, governments would commit to reforms aligning their agenda to the sustainable development goals and the Paris agreement and come up with a green recovery strategy.

“It’s important that these schemes don’t have green conditionality, in the sense that northern countries don’t dictate what green means,” Gallagher said, emphasizing that every country has its own adaptation and mitigation challenges.

The biggest stumbling block with such instruments, he continued, would be to incentivize countries that are heavily reliant on oil and gas exports to keep fossil fuels in the ground.

“It’s morally wrong and economically irresponsible to ask fossil fuel exporting economies to halt exports without alternative sources of financing that can lead to a sustainable green economy,” Gallagher said. Instead, he suggested, countries could consider swapping fossil fuel subsidies for renewable energy subsidies.

Fresnillo said that if country sovereignty is respected and investment needs are decided by the countries themselves, “then it’s worth it.” She also called for more climate financing, but pointed out about two-thirds of climate financing so far comes via loans and not grants. The calculations are based on OECD data and are broken down in a December 2020 report, she wrote.

“We are actually making it impossible to tackle the climate emergency,” Fresnillo said. “We ask for those debts to be repaid and we put more pressure on [countries in the developing world] by offering this climate finance like it would be generous, but it’s also loans.”

While the upcoming green debt swap proposals from the IMF and the World Bank won’t offer the systemic changes needed to tackle debt, she added she’s optimistic because “we were never this close to getting this re-assessment of the debt-sustainability concept.”

“Mother nature is holding the clock here,” Gallagher said. “It’s not just about nickels and dimes — it’s about the world trying to save itself from the effects of climate change. We know that if we kick the can, it will cost us more down the road.”

This coverage exploring innovative finance solutions and how they enable a more sustainable future, is presented by the European Investment Bank.