CANBERRA — When a disaster strikes, children’s education is among the many casualties. A new program in Indonesia is working on new ways to encourage children to return to school.

The Innovation for Indonesia’s School Children program, or INOVASI — a partnership between Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Indonesia’s Ministry of Education and Culture — seeks to better understand barriers to quality education and support a locally driven approach to solutions.

“Disasters certainly can impact the learning process,” Sri Widuri, education specialist at INOVASI, explained to Devex.

North Lombok is among the regions where INOVASI schools operate. Following two earthquakes that hit the island in August 2018, INOVASI sought to engage local government bodies, school principals, teachers, parents, children, communities, and local organizations to identify the priority challenges and local solutions that could support children returning to school.

The priority issues following a disaster

Approximately 80 percent of structures across the district were damaged or destroyed following the earthquakes. A total of 563 people were confirmed killed, more than 1,000 were injured, and the number of displaced in, excess of 417,000.

When the earthquake struck, teaching and learning were temporarily disrupted, with aftershocks continuing to interrupt schooling for weeks, Widuri recalls.

INOVASI partner schools were among those damaged and required temporary classrooms and shelter along with new strategies to enable a return to learning. This in itself posed a challenge.

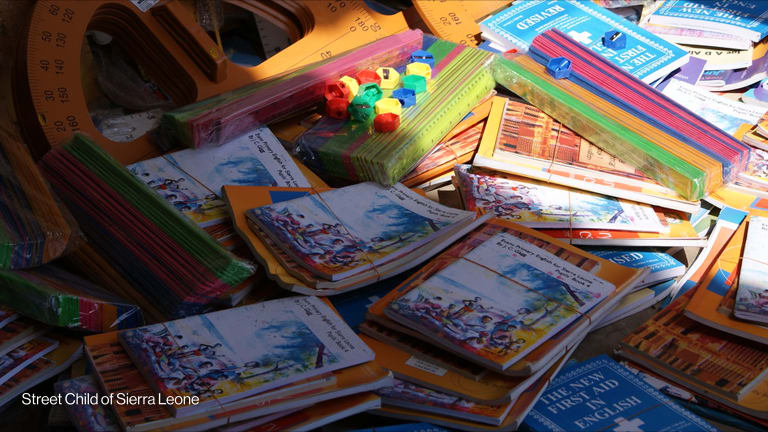

“We found there were three main challenges when conducting education in temporary accommodation,” Edy Herianto, INOVASI Nusa Tenggara Barat provincial manager, explained to Devex. “Firstly, the enthusiasm of the teachers to carry out their duties, even though the classroom isn’t the same … Secondly, the availability of proper learning facilities and school assets was difficult, including teaching aids for students — like books. And finally, there was a need for synergy between stakeholders in order to restore the learning situation to what it was before the earthquake.”

INOVASI began to work with local stakeholders, including families and local communities, to devise new strategies to improve educational quality in the aftermath of the earthquake.

More education news:

► Q&A: Sarah Brown on the need for safe schools

“They [families and communities] are very important,” Herianto said. “The school committee can actually play an important role in this. After the earthquake in North Lombok, school committees helped support the return of children to school. They can help involve families and communities and ensure that learning activities are as safe as they should be.”

In consulting with the teachers, the community and other key stakeholders, a range of immediate challenges were identified in North Lombok including environment, security, and teaching challenges. There were differences between the needs identified by children and those of adults in the community as part of the consultation sessions, Widuri said.

“Children really wanted to be able to return to school, like before the disaster,” he said.

Local solutions

Following the consultation that occurred in October 2018, it was decided that the most appropriate solution was to conduct psychosocial education, offering enjoyable activities for children and adults after difficult situations.

While psychosocial education is part of the available curriculum in Indonesia, it is not commonly used or understood by teachers. With the support of INOVASI and the Indonesian Guidance and Counselling Association, teachers were supplied school kits to assist children in adapting to their new environment as well as the tools to deliver education activities to support children who experienced trauma during the earthquake.

“Through the psychosocial education activities, we trained teachers and principals to learn simple strategies for identifying children who needed more support,” Widuri explained. “In cases where school support was not sufficient, the child could be referred to other community and post disaster organizations who were in a better position to help.”

And by developing simple weekly lesson plans and using available materials in the local village, they could be responsive to the changing recovery conditions.

“Some teachers began to integrate aspects of the recent earthquakes into teaching and learning, so this definitely changed the types of discussions inside the classroom,” Herianto said. “They talked about natural disasters, and how people can handle them.”

The response from teachers and communities has been positive.

"Even though schools were destroyed, and books didn’t exist, we could start learning around us, observe plants that grow, parts of plants, and calculate tree height," Laili Muniroh, a teacher at the primary school 4 Malaka, explained as part of INOVASI feedback.

With the concurrent earthquakes and aftershocks, the response also needed to take into account the fear of continued disasters — which Widuri said creates both positive and negative impact. While he said children are stressed and traumatized by the loss of houses or members of their families, the disaster has also brought together families, communities, and school members to be more resilient.

But returning to normal, in education and life, is something that may never be achieved for any children who have experienced disaster due to the unpredictable nature of disasters — which is why, Widuri said, education needs to adjust.

“The system and its environment has created a new normalcy for the community,” he said. “In this new context, school learning spaces, schedules, assessment, and psychosocial education will continue on, but just differently to before.”