NAIROBI — Despite global gains in securing sexual and reproductive rights over the past 50 years, many population groups are still left behind, according to a report released Wednesday by the United Nations Population Fund.

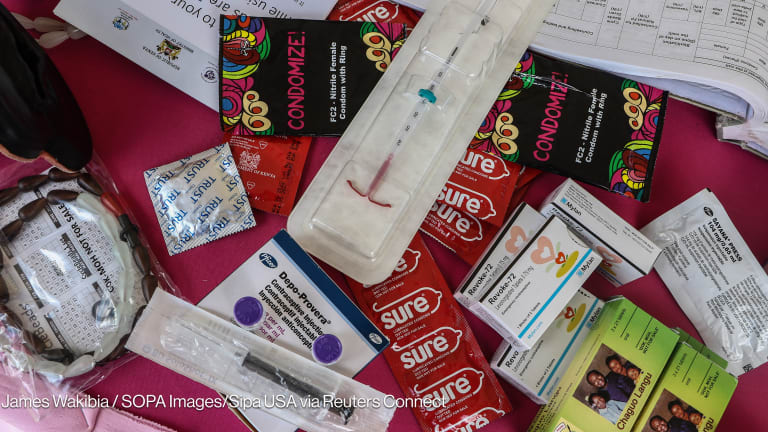

The “State of World Population 2019” report shows that global fertility rates have roughly halved since the agency began operations in 1969. But it also highlights how reproductive rights remain inaccessible to many, including more than 200 million women worldwide who want to prevent a pregnancy but don’t have access to contraceptives.

Contraceptive prevalence for women in relationships globally is 58%, but only 37% in West and Central Africa, and 7% Chad and South Sudan.

— “State of the World Population 2019”“The lack of this power — which influences so many other facets of life, from education to income to safety — leaves women unable to shape their own futures,” UNFPA Executive Director Natalia Kanem said in a press release.

Inequalities exist both within and between countries when it comes to sexual and reproductive health and rights, according to the report, for reasons including income inequality; insufficient health facilities, providers and supplies; legal barriers; lack of education; and cultural norms.

Contraceptive prevalence for women in relationships globally was 24% in 1969, while it is 58% this year. But in West and Central Africa, still only 37% of these women are using contraceptives. In Chad and South Sudan, it is just 7%, according to the report.

Gaps in access to sexual and reproductive health services also disproportionately impact marginalized groups. For example, women and girls with disabilities are often not seen as needing information about sexual and reproductive health, according to the report. A study in Ethiopia found that only 35% of young people with disabilities used contraceptives during their first sexual encounter and 63% had an unplanned pregnancy.

Other marginalized groups with lower levels of access to SRHR globally include ethnic minorities, indigenous people, sex workers, the women and girls living in highest levels of poverty, and the LGBTI community, who face barriers including poor quality health care, resource gaps, discriminatory laws, and dismissive attitudes from service providers.

The report notes that while reaching these groups is difficult and expensive, it should be a “central priority” of the development community. Services should be “tailored to the needs they express, confidential, and free of judgement or coercion,” the report states. This could include training and sensitizing of health care workers on working with individuals of different genders and sexual orientations.

Some low- and middle-income countries have successfully reached these marginalized populations. In Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, and Thailand, for example, contraceptive rates are actually highest among the poorest 20% of the population, as opposed to the wealthiest 20%, thanks to efforts targeting the populations hardest to reach.

Financing methods, such as vouchers that can be exchanged for services and conditional cash transfers, have also been effective, according to the report.

A UNFPA conference in Nairobi, Kenya, in November will examine the progress made on the promises laid out in 1994 during the Cairo International Conference on Population and Development, where governments linked sustainable development to reproductive health, women's empowerment, and gender equality.

“I call on world leaders to recommit to the promises made in Cairo 25 years ago to ensure sexual and reproductive health and rights for all,” Kanem said.