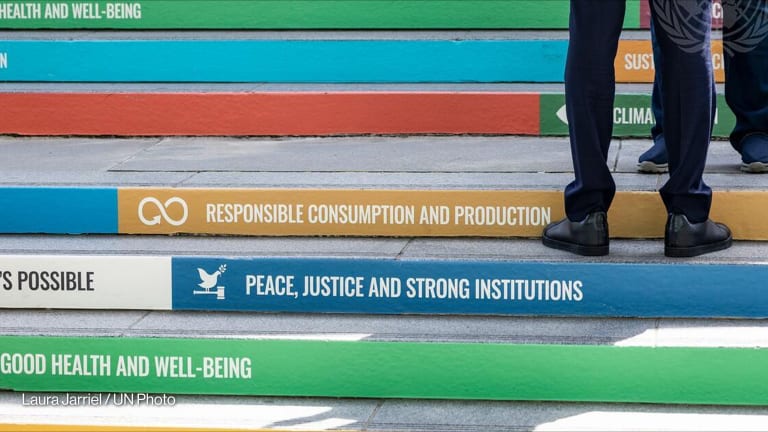

Time is running out fast for the delivery of ambitious new global development goals on target by 2030. A report from a high-level working group of European development experts has rightly pointed out that these global goals cannot be achieved without progress on Europe’s own development priorities: climate change, Africa, and the European neighborhood.

The report — written by the High-Level Group of Wise Persons on the European financial architecture for development — maps out a blueprint for the realization of those European development goals. It also highlights key development principles and sketches out potential institutional scenarios including roles for organizations, such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which has been my honor to lead for the past seven years.

As far as development principles are concerned, the report reflects the clear consensus now on the importance of the private sector as a source of financing that creates jobs, sparks innovation, forces market discipline, and achieves scale.

It also puts a strong emphasis on development impact, a policy-first approach, the institutional importance of an inclusive shareholding model, and strong technical expertise with experience on the ground.

More on Europe and reaching the SDGs

► A single market for European philanthropy? (Pro)

► 4 years later, is it any easier to track the SDGs?

► Funding access to justice, a 'cross-cutting enabler of the SDGs'

Given the urgency of the challenges, the report makes short-term recommendations, including the need to maintain “open architecture” that guarantees that those development institutions best suited to deliver the multiple aspects of the EU’s development policies should receive the funding they need.

“Open architecture” means that all international and national development institutions are invited to participate in the process to the best of their abilities. This approach is the most effective way to put the strengths of all actors in the European system to work on the EU’s external priorities.

Looking to the future

The longer-term recommendations look ahead to institutional options. In this context it is helpful to outline what I see as the key attributes of EBRD: it is a global bank with a European heart; its establishment is linked to a unique moment in Europe’s history — the fall of the Berlin Wall 30 years ago.

The institution was created at a time when Europe reached out beyond its frontiers and helped countries that were lagging behind, and became the very symbol of a collective response to an urgent challenge of staggering dimensions. The countries that EBRD supported became shareholders, countries of operations, and ultimately partners.

While the bank has an EU majority by charter — which will remain unaffected by Brexit — and the EU has significant say and influence in shaping the institution, EBRD is also global, consisting of 69 shareholders plus the EU and European Investment Bank. This shareholding includes all the countries where the bank engages in policy dialogue and provides financing, as well as shareholder countries such as the United States, Canada, and Japan. It embodies the inclusive ownership that the report sees as an integral part of a modern vision of partnership with recipient countries.

Indeed, at a time of worrying increases in isolationism and nationalism, it is only through internationalism and partnership that we can hope to overcome global development challenges.

And nowhere is that partnership more clearly demonstrated than when the international community collaborates to pursue common goals through the multilateral development banks that act in the interests of a collective good.

At the same time, private sector development and private finance — so crucial to delivering both European and global development goals — are at the heart of the EBRD’s unique mandate and business model that combines successful and profitable investment with long-standing reform engagement.

Delivering on the development agenda

The institution has also demonstrated its ability to establish a deep local presence through the use of policy dialogue to open up new opportunities and expand the pipeline of banking projects. These are all relevant to the delivery of Europe’s development priorities and global development goals. For example, from driving reforms in Ukraine and supporting peace and stability in the Western Balkans to creating sustainable economies and jobs in the Middle East and North Africa.

Well on the way to exceeding its target of dedicating 40% of annual investments of close to €10 billion ($11 billion) by 2020 to climate action projects, EBRD is also demonstrating its contribution to meeting the global goals of the 2015 Paris climate accords.

And if the shareholders decide to do so, EBRD can do even more. More on climate, more on small business support, more on governance reform — more in all areas where the bank can make a contribution that is otherwise not yet available.

This business model may also be appropriate in parts of the world where we are not, so far, working. Ranging from economic development to climate change, and from the eradication of poverty to tackling the causes of mass emigration, Africa is the biggest global development challenge.

We are currently carrying out detailed analysis that we will present to shareholders on the added value EBRD might be able to bring to some countries in sub-Saharan Africa, expanding from where we already are in Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia.

It is vital that institutions respond to the demands and priorities of all of shareholders with the clear aim of helping to deliver a development agenda that the world so urgently needs. The time is now — 2030 and the completion of the Sustainable Development Goals will be with us before we even realize it.

Search for articles

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5