One of humanity’s gravest existential threats is invisible. Pandemics are silent killers and have prematurely ended the lives of more people than virtually any other cause.

Some outbreaks have been more consequential than others. A typhoid outbreak in 430 BC killed as many as a quarter of the Athenian army, permanently crippling it. The bubonic plague from 541-750 AD killed off as much as 25-50 percent of the planet’s human population. The Black Death lasted from 1331 to 1353, killing some 75 million people around the world. Meanwhile, smallpox, measles, and influenza introduced by European explorers to the New World wiped out up to 95 percent of indigenous populations in the Americas.

Most states are still failing to meet minimum international standards to detect, assess, report, or respond to major public health threats.

—Naturally emerging infectious diseases have generated drastic health, economic, and security impacts for millennia. Pandemics are essentially epidemics that are communicable and cross an international boundary affecting a large number of people.

Today, many pathogens are household names: Ebola, Middle East respiratory syndrome, SARS, Zika, Chikungunya, yellow fever, and influenza are prominent examples. Part of the reason they are so well-known is due to their devastating legacies. To take just one recent example, the 2009 swine flu H1N1 pandemic resulted in over 248,000 deaths worldwide.

More frequent outbreaks

CEPI, a year in: How can we get ready for the next pandemic?

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations launched a year ago, at the 2017 World Economic Forum annual meetings. Devex met with leaders behind the initiative in Davos last month to check in on its progress.

According to public health experts, the frequency of disease outbreaks is rising. Between 1980-2013 there were over 12,000 recorded disease outbreaks involving 44 million cases in every country. Every month, the World Health Organization traces roughly 7,000 new signals of potential outbreaks and undertakes 300 follow-ups, 30 investigations, and 10 full field assessments.

In June 2018 there were — for the first time — outbreaks of six of WHO’s eight "priority diseases" at the same time. Had any of them spread more widely, they could have killed tens of thousands of people and triggered massive global disruption.

At least five underlying factors seem to be quickening up the risk of pandemics.

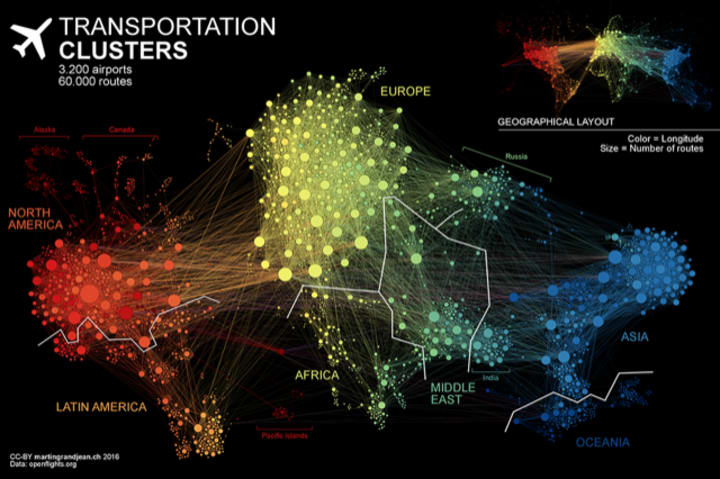

The first factor contributing to the increase in pandemics is globalization — or more specifically surging travel, trade, and connectivity. A single disease outbreak can move from a remote village to a global city in less than 36 hours. No surprise, then, that in a matter of days, travelers introduced cases of Ebola to the United States and Europe from Africa; severe acute respiratory syndrome was imported to North America from Asia; and MERS was transported from Saudi Arabia to South Korea.

A second factor is increasingly high-density living, especially in informal settlements. Today over 55 percent of the world’s population live in cities, more than 3.9 billion people. Roughly 1 in 7 urban dwellers lives in a slum. The world’s urban population is set to grow even larger, with over 90 percent of all future city growth to occur in Africa and Asia. Megacities and sprawling informal settlements serve as incubators for new epidemics.

The third factor is massive environmental degradation. While the exact relationships between forest-cover loss, reductions in biodiversity, and pandemics are still being investigated, over 30 percent of recent outbreaks of Ebola, Zika and Nipah viruses were linked to tree-cover loss. Recent studies suggest a strong correlation between recent deforestation events and the outbreak of hemorrhagic fevers such as Ebola. What is more, the migration and dispersal of birds due to habitat degradation could expose populations to novel pathogens including avian malaria, new parasites, and viruses.

A fourth factor, climate change, is increasingly being linked to the acceleration of infectious disease transmission, especially malaria, dengue, yellow fever, and Zika. As temperatures rise, disease vectors such as mosquitoes and ticks can also grow alongside them. Extreme weather events can also create conditions for infectious diseases such as measles or cholera. Meanwhile, droughts and food insecurity can also lead to greater reliance on bush-meat in some countries — raising risks of Ebola and hantavirus outbreaks.

Finally, population displacement due to war, disaster, development schemes, and the pursuit of better economic opportunities increases the movement of vectors and vulnerability to pandemic threats. The most susceptible to such disease are displaced populations themselves. Among refugees, for example, measles, malaria, diarrheal diseases, and other infections account for between 60-80 percent of all reported mortality.

One paradox is that many of the virtues of globalization — the accelerated movement of people and products and the development of new technologies — risk increasing vulnerabilities to infectious disease outbreaks. The massive expansion of agrofood industries, the externalization of the costs of climate change, and the dramatic availability and use of new drugs is hastening the spread of pandemics.

A worrisome symptom of this is the spread of antimicrobial resistance — and the threat of superbugs — which appears to be increasing in people, animals, food, and the environment. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, every year 2 million Americans experience infections that are resistant to antimicrobial drugs used to treat them — resulting in an annual death toll of 23,000.

More on antimicrobial resistance:

► Are we making progress on the use of antimicrobials in animals?

► Q&A: Sally Davies on the rising threat of antimicrobial resistance

Notwithstanding advances in health and medical breakthroughs such as vaccines, antivirals, and antibiotics to reduce the spread and lethality of pandemics, the economic costs are considerable. The 2003 SARS outbreak that infected about 8,000 people and killed 774 cost the global economy some $50 billion.

According to a study produced by the Brookings Institution a decade ago, a mild pandemic could cost the world some 1.4 million lives and reduce global economic output by 1 percent, or roughly $330 billion — in 2006 prices — in the first year. By contrast, a massive pandemic could kill as many as 142 million and cost the global economy some $4.4 trillion, or 12.6 percent of global gross domestic product in year one.

Complacency is not an option

To mobilize attention and resources, WHO introduced a priority disease list in 2015 that it updates every year. The goal is to highlight where research and development is most urgently needed. In 2018, WHO added "Disease X" to its list to draw attention to pandemic risks from diseases that cannot yet be transmitted to humans. The organization is simultaneously working to incentivize vaccine development — such as the production of an effective Ebola vaccine in 12 months rather than the usual development cycle of 5-10 years. These innovations don’t come cheap. The minimum estimated cost of developing a vaccine for each of the 11 infectious diseases identified by WHO comes in at between $2.8-3.7 billion.

Preparedness is the watchword for the 21st century. While progress is being made, most states are still failing to meet minimum international standards to detect, assess, report, or respond to major public health threats. When outbreaks hit, as they surely will, responses are still likely to be absent, delayed or stretched too thin.

The cycle of neglect, carelessness, and panic that follow pandemics is lethal — not just on the frontline where outbreaks occur, but to populations across the planet.