The stakes are high as education policymakers from more than 100 countries gather in Paris, France for urgent talks on how to rescue education systems in some of the world’s low-income countries.

The two days of meetings, starting Tuesday, are designed to lay the groundwork for the Transforming Education Summit, being held in New York in September on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly.

Stefania Giannini, head of education at UNESCO, which is hosting the meetings, described the summit as a significant opportunity to spotlight the “silent” and “invisible” education crisis that has been exacerbated by school closures caused by COVID-19. The aim is to secure political commitment from heads of state to recover those learning losses, and also transform education systems for the future.

“If countries don’t prioritize education now, they will never recover from the shock of COVID-19 which really amplified … the [ongoing] learning crisis,” Giannini told Devex, before going on to add that “they will not be able to form their societies, their economies … and fulfill their 2030 [Sustainable Development Goals] agenda commitments.”

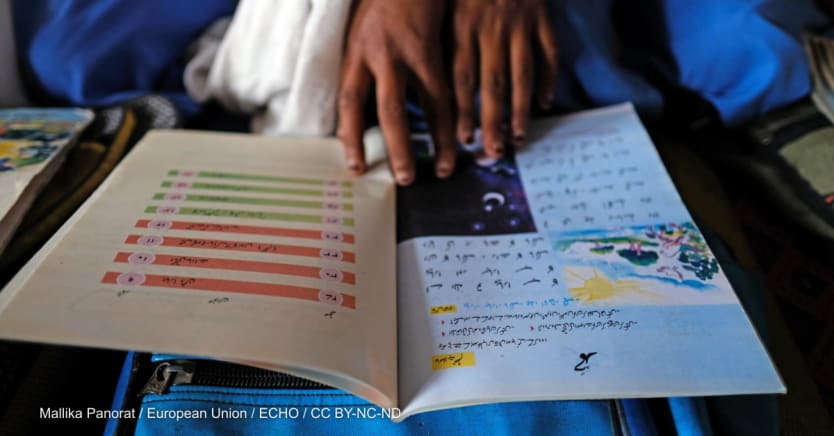

The call comes as new data from the World Bank reveals how far low- and middle-income countries are from meeting the SDG education targets that call for free universal primary and secondary education by 2030. According to the bank, nearly 70% of children in these countries are unable to read a simple sentence by age 10. This is up from an estimated 53% before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Watch: The urgency and harsh truths of transforming global education

Education is key to a country's success, yet too many nations are failing to educate their children. Leonardo Garnier, a special adviser at the U.N., discusses why the Transforming Education Summit could be a "tipping point" in tackling this crisis.

Despite these alarming figures, two-thirds of LMICs have cut education spending since the beginning of the pandemic, while foreign aid to education has flattened. The ongoing war in Ukraine, food shortages, and post-pandemic economic recovery are likely to see support dwindle even further.

“Education is a silent crisis; you don’t see the dead bodies,” Jaime Saavedra, head of education at the World Bank, told Devex. “It is true that we have several competing crises …[and] unfortunately at the same time … we have this other [learning] crisis and if we don’t do something it will have a gigantic impact on our future.”

The big challenge will be getting ministers to “internalize the magnitude” of the education crisis in their countries and securing concrete commitments to address it, he added.

While additional finance will be key to any education transformation, the summit’s success should not be defined by promises of more cash, according to Robert Jenkins, head of education at UNICEF.

“TES should not necessarily be a pledging event … but we need to protect, and ideally increase, public resources from donors but also national governments to support the recovery,” he said.

Preparations for the summit follow three main paths: national consultations, five “thematic action tracks,” and engagement to mobilize public support for education, particularly among young people. The action tracks are designed to highlight promising, scalable policies to address specific education challenges, including the school environment, teachers, digital learning, and financing, which would be more focused on increasing domestic resources for education than new financing mechanisms and donor funding.

While some education insiders described the preparations as rushed — kicking off in April, just five months to the summit — Giannini said things were progressing well.

“Some countries expressed concern at the beginning, [asking] how can they do it in a few short months, but in two months we have already 100 countries running their national consultations,” she said.

A narrower focus?

While turnout for the June pre-summit and September summit looks set to be high among policymakers, education insiders described “tensions” behind the scenes over the agenda, with

some donors and campaigners calling for a narrower focus.

“There is an urgent need for more focus … especially around foundational numeracy and literacy and education in emergencies,” according to Joseph Nhan-O'Reilly, executive director of the International Parliamentary Network for Education. “TES risks complete failure unless we see a focus on this,” he added.

In countries where basic literacy levels are low, it would be “sensible” to focus on improving early childhood education, Saavedra said. “Sometimes people say, ‘Kids have to be educated on climate change or in citizenship.’ Of course, they need that but how can I educate them on that if they cannot read?”

In response, Nigeria-based advocacy group Human Capital Africa, which is funded by the Gates Foundation, has been campaigning to get foundational learning, also known as FLN, its own dedicated “action track” as part of the summit.

However, others say a broader and more ambitious agenda will get better traction with ministers.

“Focusing on basic literacy and numeracy is colonial and reductionist. The starting point needs to be ambition,” David Archer, head of participation and public services at ActionAid, who is convening the financing action track at the pre-summit, told Devex.

This is supported by research from the Center for Global Development, which polled more than 900 policymakers across 35 low- and middle-income countries about their education priorities. The survey revealed that most don’t see basic literacy as the core goal of education systems. Instead, they put more weight into prioritizing universal secondary education, technical and vocational training, also known as TVET, and creating dutiful citizens. The report also revealed that most officials overestimated the share of pupils able to read in their country.

Talking about South Sudan, former education minister Deng Deng Hoc Yai said financing FLN and TVET were not mutually exclusive.

“Education starts with literacy and TVET is very expensive and university education is seen by some critics as a luxury. So, there is that tension. But the government has to strike the balance and apportion its budget for these priorities,” he told Devex.

Liesbet Steer, executive director of the Education Commission, said the education sector needs to think beyond FLN and embrace a “systems” approach that highlights the importance of education for other sectors such as climate change, economic development, and health and nutrition. For Steer, a successful TES is one that gets talked about at other summits.

“Is the COP 27 going to refer to this education summit? Is the … G-20 going to talk about this? If not, we’ve basically failed. And that goes back to why I am worried about this foundational learning approach because it makes it even smaller with the education [sector]. How are we going to reach out to other sectors if our angle is that?”

Tipping point

For Giannini, such debates miss the point of the summit, which is about securing political buy-in for education, she said.

“It’s a political process, it’s not a technical discussion between educators and the usual suspects having a debate on what to do now ... it needs to be a tipping point to boost political commitments and actions,” she said.

This was echoed by David Edwards, general secretary of Education International, who described it as imperative that TES is not derailed by “turf wars” and infighting within the education community.

“Having heads of state coming together on both a global and national stage where they will be fact-checked and held accountable … I can’t remember an opportunity like this … if we squander this opportunity then it’s on us.”