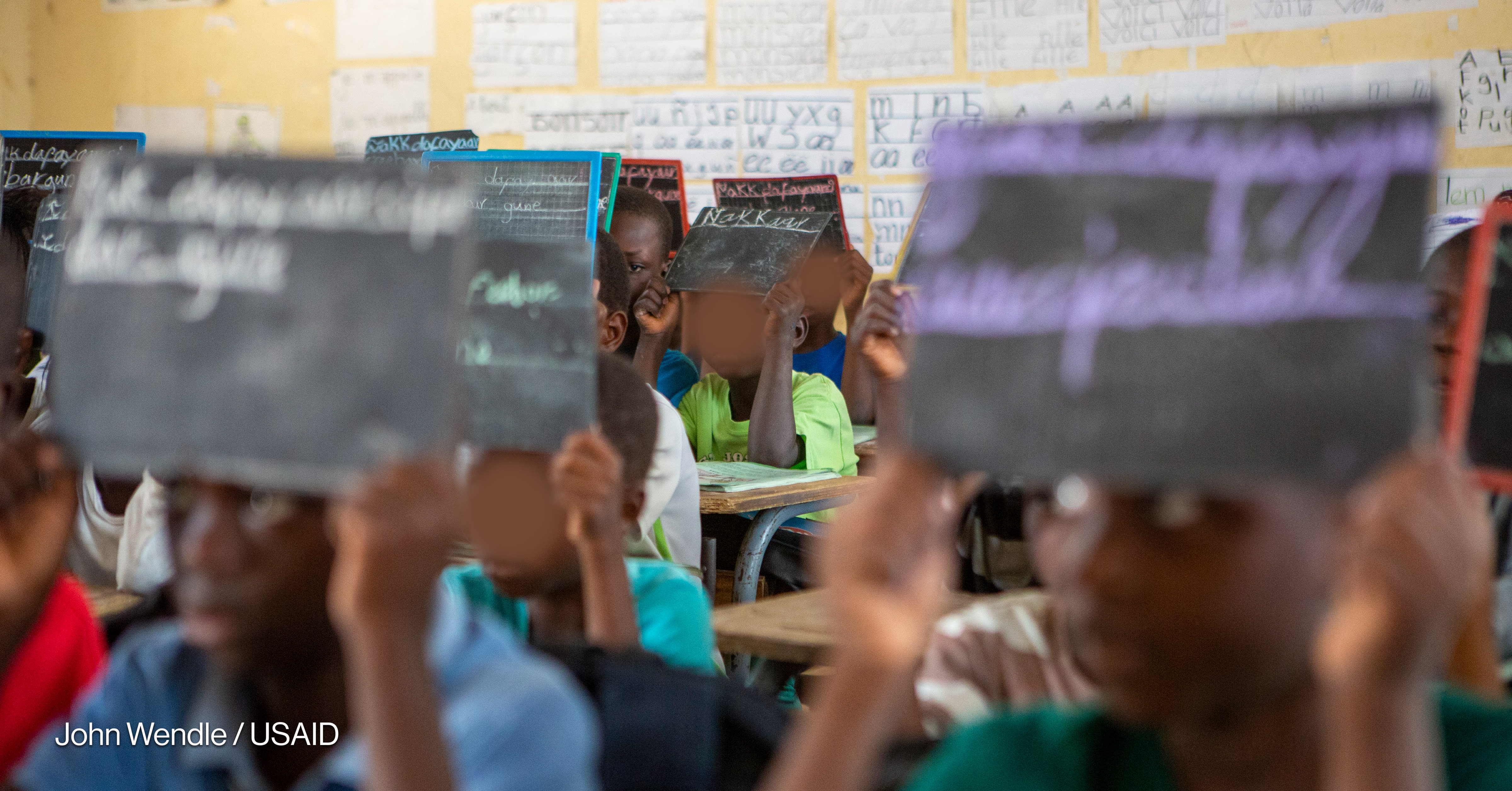

The COVID-19 pandemic was supposed to be a big moment for educational technology, or ed tech, with schools that faced closures turning to apps, tablets, calls, and other means to teach students remotely.

But for much of the world, “that just hasn’t ended up being the case,” said David Evans, a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, during a recent event on education policy in low-income countries after the pandemic. Rather, a lack of reliable electricity, broadband connectivity, and affordable devices has limited many students’ access to interactive online learning.

“What that means is that you have a learning program that is only catering ... to the richest students, those who, honestly, even without a serious intervention — whose parents would probably be investing in other ways of making sure that their kids keep up,” Evans said.

“Often the focus is placed on hardware—not enough on appropriate software that will be accessible across different socio-economic statuses.”

— Nompumelelo Mohohlwane, deputy director for research, monitoring, and evaluation, South Africa’s Department of Basic EducationSchool closures during the pandemic forced 1.6 billion students out of classrooms worldwide. And critics say ed tech has failed to deliver, calling the sector overhyped. Simulations from the World Bank suggest that COVID-19 school closures could result in sizable learning losses, equivalent to between 0.3 and 1.1 years of education, with disproportionate impacts on already vulnerable groups.

But the way to reverse those losses may not require the latest and greatest in emerging technology. Instead, low-cost and relatively simple ed tech solutions can ensure more equitable access to interactive online learning, both during the current pandemic and in any future disruptions to schooling, experts told Devex. They cited examples including text messaging, phone calls, and radio — but said that nothing tops getting kids back in school.

Some students were able to transition more seamlessly from classrooms to platforms such as Zoom, with the support of parents and caregivers. But many children around the world fell much further behind in this shift.

In parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia where fewer than 20% of people have access to the internet, virtual learning during COVID-19 often meant watching educational television programs, Evans said.

“We do have evidence on the effectiveness of TV. … We have a lot of evidence that ‘Sesame Street’ has been really effective at boosting learning,” he said. “The distance learning programs ... in low- and lower-middle-income countries are not like ‘Sesame Street.’”

Evans said these programs are put together quickly, with teachers merely reading lessons aloud and not interacting with students. And access to television is limited, too. In a sample of students enrolled in a large private school network in Pakistan, CGD researchers found that the proportion of children in lowest-income households watching educational TV programming dropped from 1 in 5 to 1 in 7 during the pandemic.

Evans called for more investment in educational technology that helps all students — for example, to improve the quality of low-tech interventions where broadband access may not be available.

“Over time, of course, increasing access to the internet will help the poorest students have better distance learning experiences,” he told Devex. “But the poorest students in rural Africa are not going to have consistent internet right away. So the question for the next few years becomes: How can we use technology that most people have access to in order to improve learning when kids are out of school?”

Cellphones are one option. In Botswana, experimental evidence on limiting learning loss demonstrated significantly better outcomes when instructors called students to go over math problems sent to them via text messages.

This low-tech intervention has expanded to six other countries, said Noam Angrist — a co-founder of Young 1ove, a Botswana-based NGO focused on expanding evidence-based programs in health and education — at the Evidence for Development: What Works Global Summit last week. He added that targeted instruction via phone calls is a cheap and scalable way to deliver lessons in low- and middle-income countries.

But other results are more mixed. For example, CGD found that one-on-one phone tutorials did not boost student learning during school closures in Sierra Leone.

“There are a lot of other evaluations that are ongoing, so we’ll keep learning how to leverage existing, widely held technology most effectively,” Evans told Devex.

Some organizations turned to radio to make education affordable and accessible to the students they serve.

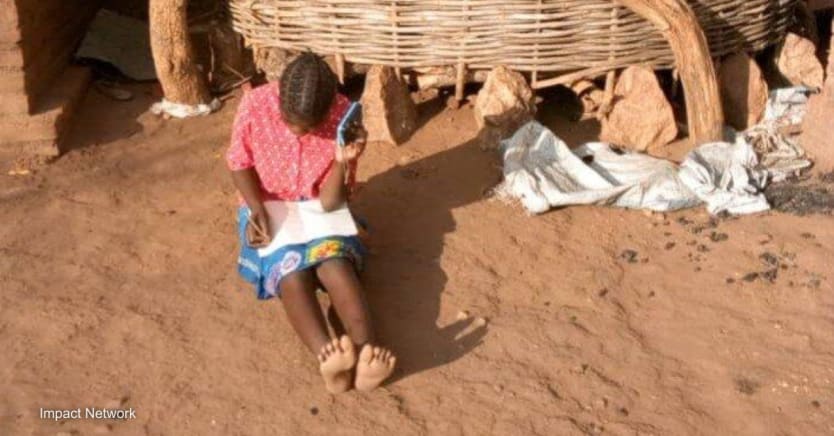

For example, 99% of the students reached by Impact Network, a nonprofit that runs community schools in rural Zambia, do not have electricity at home, said Reshma Patel, the group’s executive director. She and her team opted for a combination of radio lessons and in-person visits by teachers.

During the most recent round of COVID-19 school closures, Impact Network also introduced calls once it had gathered a phone list for students and families. But Patel noted that cellphones are not always charged, numbers frequently change, and students and parents do not always pick up.

Impact Network has prioritized at-risk students — particularly adolescent girls, given the rise in domestic violence, teenage pregnancy, and early marriage brought on by COVID-19.

But no one intervention will reach every student, Patel said.

“I don’t think you should just do one of these things,” she said. “I think you should do all of them.”

Patel also called for schools to reopen, echoing what many experts said about the challenges of distance learning compared with in-person education.

In South Africa, remote learning is not a viable option, said Nompumelelo Mohohlwane, deputy director for research, monitoring, and evaluation in South Africa’s Department of Basic Education.

“Attendance needs to go back to normal,” Mohohlwane, who is also a nonresident fellow at CGD, said during the event with Evans. “As long as we’re having the majority of children not fully at school on a day-to-day basis, we are continuing to compound the learning losses.”

Even once basic infrastructure issues around virtual learning are resolved, the problem of content remains, Mohohlwane said, referring to programs that are appropriate for the level of each student and available across 11 of the languages spoken in South Africa.

“In my experience, often the focus is placed on hardware—not enough on appropriate software that will be accessible across different socio-economic statuses—and, importantly, hardly any focus is on the content of the programs,” she told Devex by email.

Lessons from the great COVID-19 distance learning experiment

The pandemic put ed tech through its paces — and in lower-income settings, it was often outshone by simpler solutions.

Programs should consider ways to support students who are struggling and to ensure that teachers receive training to use technology effectively, Mohohlwane said. And as schools reopen, low-cost and simple ed tech can play a role in covering or reinforcing content that students may not have learned amid school closures, she said.

These interventions can complement in-person schooling and also combat learning loss during holiday breaks, teacher strikes, natural disasters, and future health crises.

“Learning loss during regular school holidays is a well-documented challenge in both rich and poor countries, so preparing for the next pandemic can also help solve a problem that countries face year in and year out,” Evans said.

Even now that many classrooms around the world are reopening, he added, school systems and their partners can use vacations to experiment with the best ways to keep children from forgetting what they’ve learned.