Two days ahead of International Universal Health Coverage Day, today is Human Rights Day. Mental health provides a critical bridge between the two. Our new report lays out why.

Hundreds of millions lack access to the high-quality and rights-based mental health support and services they need. This results not only in poor mental health outcomes, but also poor general health outcomes, and often in failure to protect human rights. An obvious step to overcome these collective challenges is to accelerate the integration of mental health in UHC.

The integration of mental health in UHC is inextricably linked to human rights in two fundamental ways.

Firstly, the provision of high quality, rights-based mental health care to those who need and want it is a critical part of ensuring that their right to health is met. As mental health is an inalienable part of health, the right to mental health care is equally an inalienable part of the right to health. UHC, therefore, cannot fully meet its goal of promoting the right to health without the inclusion of mental health. This was acknowledged in the 2019 Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage.

People living with major depression and schizophrenia are estimated to have a 40% to 60% greater chance of dying prematurely than the general population, owing to unattended physical health problems and deaths by suicide. Overall, people living with severe mental health conditions may die up to 20 years earlier than people without these conditions.

There is also the issue of financial access, a key consideration for UHC. Figures show that more than two-thirds of countries do not cover reimbursement for mental health services in national health insurance schemes, forcing people in need to spend large sums of money out-of-pocket. To ensure that the right to health is met, the system needs to be set up in such a way as to protect service users from financial hardship.

Secondly, the integration of high-quality, rights-based mental health care in UHC can create a platform for the protection of the rights of people with mental health conditions by reducing the opportunity for abuses of their human rights. This requires the full implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

In June 2020, the final report was published by the out-going special rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. In this report it stated, “despite promising trends, there remains a global failure of the status quo to address human rights violations in mental health care systems.”

The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development has also emphasized that people living with mental health conditions can be among the most vulnerable in society and endure extreme forms of violation of their human rights.

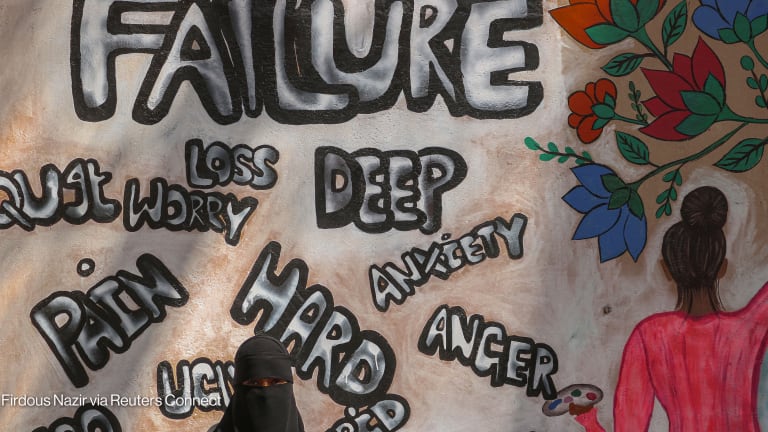

Human rights abuses, such as chaining, are commonly practiced in some communities and many people living with mental health conditions experience the complex and multifaceted burden of social rejection and abuse.

COVID-19 has further exacerbated these vulnerabilities, both at the level of institutions and within communities. For instance, people living in mental health institutions have been particularly at risk of catching COVID-19 as these institutions are often not designed for infection control and can be overcrowded.

Shockingly, on an even more basic level, there have been reports that people living with mental health conditions, often already deeply marginalized within their communities, have struggled to obtain food and other basic items during the lockdown period.

Community outreach combined with increasing the availability of rights-based, high-quality mental health care as part of UHC could reduce the opportunity for rights abuses. It could help reduce stigma and act as a key stepping stone towards realizing the CRPD, including the right to health, the right to freedom from torture, and the right to liberty and security of the person.

The case for integrating mental health in UHC inextricably is clear. However, action is struggling to follow.

What needs to happen?

Many stakeholders have a role to play. Multilateral agencies and international organizations need to strengthen the case for integration of mental health in UHC through policy development, facilitating information exchange, publishing evidence, and providing technical advice and guidance.

Mental health also needs to be included in global monitoring mechanisms such as the UHC Service Coverage index and the World Bank’s Human Capital index. At the national level, governments need to fully integrate mental health into national health legislation in line with the CPRD and commit 5% to 10% — depending on resource setting — of health budget to high-quality, rights-based mental health services.

Funders can support the integration of mental health in UHC by providing catalytic funding in those contexts where national governments are unable to fund this fully in support of a rights-based approach.

This could include the integration of mental health in priority-funded health programs such as HIV, maternal and child health, or noncommunicable diseases. Within civil society, there is a need for greater advocacy for the rights of people with mental health conditions and their inclusion in the development of all mental health strategies, plans, and implementation. Civil society should also promote UHC — inclusive of a mental health component — as a key mechanism for ensuring the right to health.

Commentators have spoken of the moral outrage caused by the fact that most people living with mental health conditions die prematurely because they are denied access to quality care and support. The abuse of the rights of people living with mental health conditions has been called a “moral failure of humanity.” The COVID-19 pandemic has put a particularly sharp focus on this failure.

Clearly, investment in high-quality, rights-based mental health services and the integration of mental health in health systems are urgently needed to reverse this injustice, and to ensure that UHC can live up to its promise of the right to health for all.

Countries around the world are reexamining their health care systems in light of the impact of COVID-19, and are looking for ways to redesign services to address future health needs.

This is an historic moment for UHC and for mental health. The time to act is now, or risk failing the very concept of UHC and leaving many hundreds of millions even further behind