Scientists are observing changes in climate in every region and across the whole climate system, according to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report released in August. But not all regions and communities are affected equally. Impacts from extreme-weather events hit low-income countries the hardest, as they are particularly vulnerable to the damaging effects of natural hazards and often need more time to rebuild and recover, according to The Global Climate Risk Index 2021.

The COVID-19 pandemic has already both exacerbated and exposed inequalities, and the impacts of climate change will be no different. A new report by Save the Children, titled “Born into the Climate Crisis” highlights that children in low- and middle-income countries will bear the brunt of impacts, including losses and damages to health and human capital, land, cultural heritage, local knowledge, and biodiversity.

“Children living in low- and middle-income countries, as well as disadvantaged communities, will be hit the hardest because they are already at risk for waterborne diseases, hunger, and malnutrition, and their homes are often more vulnerable to increased risk of cyclones, floods, and other extreme weather events,” said Sultan Latif, director of the humanitarian climate crisis unit at Save the Children.

Devex spoke to Latif about the ways the climate crisis is disproportionately impacting vulnerable children, the importance of giving youth a seat at the table in climate discussions, and how his unit is using data science to predict crises and take action earlier.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Children have contributed least to the climate crisis, yet they are the ones who will suffer the most. In what ways is climate change disproportionately affecting children?

The climate crisis — at its core — is an intergenerational child rights crisis, and it’s a severe threat to children’s survival, learning, and protection. Inequity is at the heart of it. Our report, “Born into the Climate Crisis,” analyses and shows this inequity across generations.

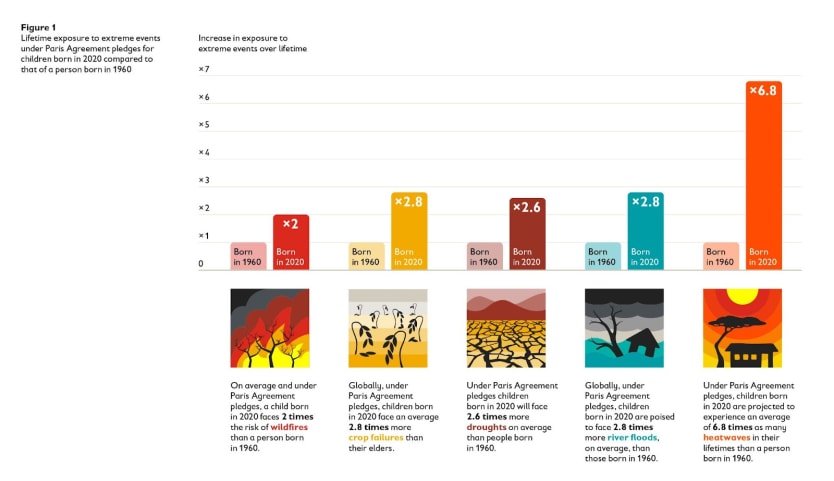

As an example, children born in 2020 will be far harder and more often hit by the [climate] crisis in their lifetime than their grandparents were. And children in low- and middle-income countries — as well as in disadvantaged communities — will be worst affected too. While children in North America and Western Europe are less likely to suffer the consequences of crop failures, newborns in sub-Saharan Africa will face 2.6 times more crop failures than their elders. Children in the Middle East and North Africa, [will experience] up to 4.4 times more [crop failures].

In what ways are the impacts of climate change disrupting children’s lives and impacting their rights?

Essentially, the climate crisis threatens child rights and its worsening inequality. It both threatens children’s rights by disrupting their education, forcing them from their homes, [decreasing] their food security, and more. It’s also important to note that [the] U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child applies to all children everywhere, but the climate crisis is harming the children most affected by inequalities and discrimination first, and worst, so that differentiator is very important to be aware of.

Additionally, it’s critical that children and their opinions are included in the decision making around the climate crisis. That was our intent around this report as well — Save the Children developed this report with the support of a child reference group, consisting of 12 children from the ages of 12-17 from across the globe, who shared how climate change has impacted their lives.

The new report also highlights that the window of opportunity to make a difference for children is quickly closing. What needs to happen to reverse this?

The window of opportunity to make a difference is closing and we need to act now, but there is still hope and optimism. A few of the suggestions are for governments — but also for corporations because they play a big role — to act urgently to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius as was agreed [to be pursued under] the Paris Agreement.

We definitely need to increase financial commitments to help vulnerable communities deal with and recover from climate disasters and shocks. These communities deal with these events on a recurring basis — it’s not just a one-time thing — so increasing financial commitments to help them needs to be there on an ongoing basis, not just as one-time-event solutions.

We also need to increase social protection systems to address the increasing impacts of climate shocks on children and the communities they live in. And then finally, we need to ensure that COVID-19 recovery efforts go beyond simply restoring business as usual or what it was before; we need to move towards building a better, greener, and more equal future for children.

“The climate crisis — at its core — is an intergenerational child rights crisis, and it’s a severe threat to children’s survival, learning, and protection. Inequity is at the heart of it.”

— Sultan Latif, humanitarian climate crisis unit director, Save the ChildrenYou lead the humanitarian climate crisis unit at Save the Children. Can you tell us more about how you’re working to solve some of these issues for children?

Our aim is to address the ever-evolving climate crisis and how it pertains to our work, our programming, and our efforts globally. And we do this by advancing research into climate change’s impacts on children, by developing and enhancing predictive analytics processes to better forecast climate events before they happen, and by responding to those forecasts in advance so we may prevent a full-scale humanitarian crisis.

By anticipating crises before they happen, we can more successfully combat the impact of the climate crisis on the communities we work with. Really the intent is to act early based on data and forecasts, and not react to crisis events after they happen.

How is the unit also using data and technologies to help solve some of these issues? Can you give a few examples?

Data and technology is crucial when it comes to anticipating climate shocks and acting early. We want to use data to make [an] informed decision on whatever climate indicator we are looking at — whether it’s a community that faces flooding, or one that faces cyclones — we need to look at how data is assessed and analyzed in order to make decisions to respond early in a systematic way to prevent full-scale damage.

This year, we conducted a pilot program in the Sirajganj district of Bangladesh. The goal was to improve the community’s abilities to anticipate floods — looking at the impacts of floods on children and caregivers specifically. We used a trigger model to indicate when conditions called for early actions against flooding.

Once levels reached a certain threshold, [a] trigger was activated where we responded with specific early action activities to prevent that full-scale damage from when the flood does actually arrive. It’s a very interesting model in a response system that is relatively new to the humanitarian and development sector.