Mental health care on its own is not enough, and specialized care that caters to the various needs of young people is crucial, advocate Grace Gatera said ahead of World Mental Health Day on Sunday, Oct. 10.

Born in Burundi, Gatera was visiting relatives in Rwanda when the 1994 genocide broke out, and she was forced to flee with her family to Uganda. This, compounded by other traumatic experiences, has led Gatera to experience post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression. But as a youth leader and mental health advocate working with the My Mind Our Humanity campaign, NCD Child, and the Mental Health Innovation Network, she is using her experience to push for better mental health services worldwide.

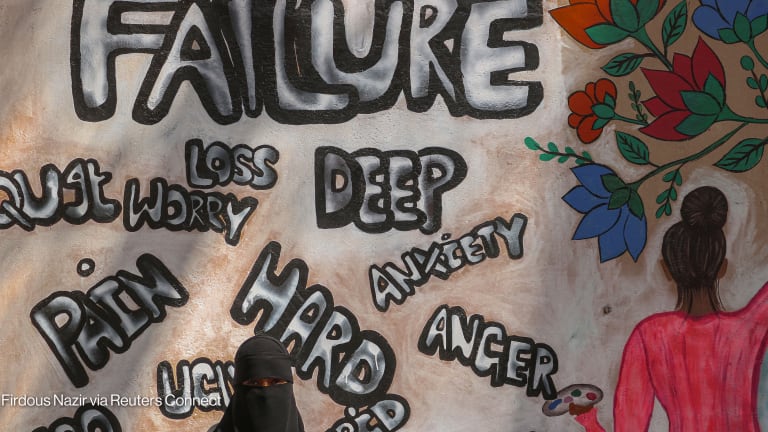

“When I started on my advocacy journey, I was young, and I remember thinking that there were very few people in the advocacy space calling for the things that people like me, young African Black girls, need — especially [those] who have gone through traumatic life experiences and have mental health challenges,” Gatera said. "But as time has gone on, it has become glaringly clear that young people need action on mental health due to the state of the world.”

How Rwanda is spearheading efforts to tackle mental health

How is Rwanda leading the way when it comes to tackling mental health? From Kigali, Devex takes a look.

According to the World Health Organization, mental health conditions constitute 16% of the global burden of disease and injury in people between the ages of 10 and 19, and half of all mental health conditions begin by the age of 14. The COVID-19 pandemic and climate change have only served to further impact young people’s mental health.

Yet they’ve also detracted focus and stalled progress. This is why, Gatera said, it’s even more urgent to focus on creating lasting change in mental health policy, service delivery, and research. That involves providing mental health specialists for young people who are refugees; who are LGBTQ or intersex, or who hold another marginalized gender or sexual identity; or who come from a rural setting.

Speaking with Devex, Gatera described what ideal mental health services for young people look like and how countries can replicate some of Rwanda’s efforts in this space.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What do you think prioritization of mental health information and services for young people should look like?

I think the thing about mental health information and services for young people is that it differs according to region and according to what the young people need. For example, LGTBQI-plus young people might need counseling, care, and service delivery catered specifically for LGTBQI-plus young people. Young people in rural areas might need special care for rural areas.

So what's important for me is the prioritization — actually putting it on the agenda of what's being talked about. … Governments across the world have to prioritize mental health care, prioritize mental health resources and services. It has to be part of their national budgets. When they present in parliament, they have to say, “This is what we have put aside for young people.”

Based on your own experience in accessing mental health services, what do you think needs to improve to give young people the mental health care they need?

I grew up as a refugee, meaning that the country I'm living in is not the one that I grew up in. When I think back to that young girl who was going through those challenges, what stood out for me a lot was the loneliness I felt because I was alienated, because I was not part of the community.

What's very urgent is that mental health services exist in the first place [and that there is] a dedicated specialist to deal with young people's mental health care. … Having a dedicated specialist would have made a world of difference for me. But I didn’t have access, mainly because of … the stigma that came with it, but then also the budget wasn’t there for it.

What do you think needs to change in terms of the way people and institutions view mental health?

This is where I think patient advocacy and people speaking from their experiences has changed the game. I think people now are more aware of mental illness, are more aware of mental health challenges, and the conversation has started. Just having trusted public sources of information about mental health would destigmatize the entire thing completely. That’s still missing very much from the public discourse both locally and globally — and especially in a country very dominated by religious talk.

“As time has gone on, it has become glaringly clear that young people need action on mental health due to the state of the world.”

— Grace Gatera, Rwanda-based mental health advocateSome of the things that led to a lot of the stigma for me was every time I had a panic attack when I was young, they would say I was possessed by demons. They would try and pray those demons out of me. … Some of my work has taken me into the villages, and some of the people tell me that they’re afraid of their fellow villagers because they think they are possessed when they are experiencing a crisis.

If we could get a public source of information to constantly give out trusted information — backed by scientists saying: “This is what mental health challenges look like. This is how to deal with people within our community. Do not isolate them. Do not say that they are attacked by demons” — I think that would change the outcomes for a lot of people like me. I think that would drive people to seek help more.

What does access to mental health services in Rwanda look like, and are there any lessons that you think other countries could learn?

They put mental health care under universal medical insurance so that it became more affordable and accessible to the people in the country. I think this is a big lesson for even higher-earning countries, because I'm pretty sure that some countries don’t put that there even though they can.

Another is that, during the pandemic, Rwanda was among the first countries in Africa to have standard operating procedures to take care of a person having mental health crises due to anxiety over the pandemic or panic about being a victim. … Part of it is because Rwanda has a lot of unfortunate reasons to be very aware of people’s mental health, with the 1994 genocide against Tutsi [ethnic group members]. … I’d ask other countries to care for their people first. Look at what your country needs, and deal with that.

Building on these successes, I think we can still do more to provide more specialized access to youth mental health care, especially since Africa is the continent with the youngest population.

What would be your one call to action around mental health?

Involve people who have lived the experience, because they know what they're talking about and we provide a great wealth of information and expertise. And I'm pretty sure we’re willing to be part of the movement — a part of the solution.