The climate emergency is turning fragile supply chains into a crisis

Disasters are increasingly putting the shaky global supply chain for medicines in the spotlight. But what can be done to fix it?

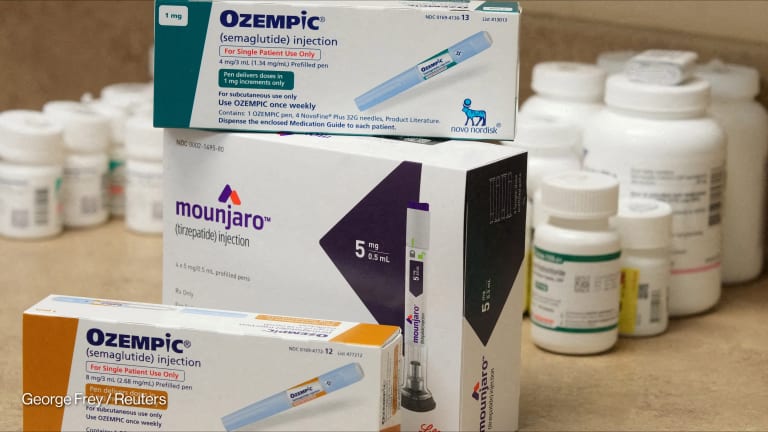

Even before catastrophic floods hit Pakistan last year, antiretroviral medicines, or ARV, were in short supply for people in the country living with HIV. Some patients were traveling up to seven hours to receive care and pick up free medicines at government clinics. When the floods began in June, facilities already stretched by the COVID-19 pandemic started to run out of lifesaving medications altogether, said Anmol Mohan, a recent medical school graduate who began investigating after ARV shortages were reported during the pandemic. “Patients didn’t have lifesaving medicines,” she said. “People had to travel, to take the whole day off and then the medicines weren’t there.” The private market became the only source for such medicines, she said, but at prices that were out of reach of many patients. That left people in danger of developing resistance to the treatment and of falling dangerously ill. With global catastrophes on the rise, experts warn the concurrence of the pandemic and climate disaster that triggered the supply chain problems in Pakistan may be less a generational event and more a preview of the kinds of multilayered emergencies that could occur increasingly often. Those emergencies could threaten to disrupt the delivery of not just ARVs, but also insulin, essential heart medicines, or cancer treatments. The threat is particularly acute in underresourced communities where access comes down to a handful of government or humanitarian services. The solution is far more complicated than strengthening the final leg of the supply chain to ensure that essential medicines still reach patients in an emergency, though that is also crucial, said Edward Wilson, the director of the Partnership for Supply Chain Management at JSI. But it involves rethinking a complex process that begins with sourcing ingredients and then manufacturing and stockpiling treatments. “This requires a long-term and fairly intensive and intentional conversation and commitment to make this happen,” he told Devex. COVID-19, he said, jumpstarted those discussions, but any tangible results are still years away from implementation. The companies that produce active pharmaceutical ingredients, or APIs — the components that actually make medicines work — and the generic drugs that supply many low-income communities are often concentrated geographically. India dominates generic production, with at least 20% of the market, and more than two-thirds of the APIs used to manufacture generic drugs come from Asia, primarily India and China. “If even one of those suppliers happens to be in a region and there’s a climate-related disaster, that puts the whole world at risk for a basic medication,” Kelly de Baene, an expert at the Access to Medicine Foundation, told Devex. In fact, in China and India most API manufacturers are clustered in just a few states, meaning that a climate emergency in those regions could have catastrophic global consequences if it interrupts API production. The solution, Wilson said, is to diversify the production of APIs and medicines. “That’s the first piece,” he said. “Taking a look at the materials that you need at the origin for the production of medicines and making sure that you have a fairly geographically spread source for those so that you’re not limited by a climate event or a health event or political event.” But pharmaceutical companies will need convincing that they will see a return on their investment. That can be particularly difficult when essential medicines treat diseases that primarily affect people living in poverty, such as tuberculosis. Companies cannot charge outsized prices to rapidly recoup their investments. There is a role for the donor community in helping to mitigate the risk, Wilson said. “If the donors can step in and provide that through either a lower-cost loan or by facilitating a guaranteed market for a period of time, then I think they could play a critical role,” he said. Governments can also attract business by investing in training a skilled workforce and getting the regulatory pieces in place that will allow both the manufacture and distribution of APIs and finished medicines. Overhauling the system for some medicines might prove easier than others, though. There are global networks that have formed around diseases such as HIV, with advocates who will fight to ensure ongoing access to needed treatments. Similar structures do not exist for medications like penicillin. “For medicines where you don’t have a global community that’s really focused on aligning market incentives from top to bottom, it’s going to be more difficult,” Wilson said. Regional and continental bodies, such as the African Union, can implement strategies to strengthen coverage — and can also help guide the distribution of plants for manufacturing APIs and medicines, to avoid overlap or clustering. Then there is the other end of the supply chain. In Pakistan, the floods exacerbated problems that already existed, Mohan said, like governmental failures to accurately forecast demand and a paucity of public facilities providing treatment. Both issues, she said, still need to be addressed. “A lot of the focus has been on trying to minimize cost and reduce inventory,” Wilson said, reflecting the “just in time” mentality that has guided supply chain services in recent years. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced a reckoning, as officials look to systems that will ensure adequate supplies are easily available even if emergencies, and particularly climate disasters, cut off traditional supply chains. That will require investments in storage facilities for medicines and in transportation networks that can withstand most climate events. It also necessitates recalibrating systems for ordering supplies, while conceptualizing backup strategies for how to deliver treatments during an emergency. COVID-19 offered some possible solutions: Health officials tapped into community health worker networks, asking them to deliver medicines to homebound patients, and authorized multimonth dispensing of medicines. Governments might also look to set up emergency plans with the humanitarian organizations that respond in the immediate aftermath of a climate disaster. Aid agencies are often trained in how to rapidly treat diseases that develop in emergencies, such as cholera, but may not have the capacity to treat people with chronic conditions. Wilson said there has been a “real shift in the recognition of the need for agile and resilient supply chains” since COVID-19 spotlighted their fragility, particularly with the rise of extreme weather events. The key will be securing the funds and coordinating the actors needed to shore them up before the next emergency. Visit the Planet Health series for more in-depth reporting on the current impact of the climate crisis on human health around the world. Join the conversation by using the hashtag #PlanetHealth.

Even before catastrophic floods hit Pakistan last year, antiretroviral medicines, or ARV, were in short supply for people in the country living with HIV. Some patients were traveling up to seven hours to receive care and pick up free medicines at government clinics. When the floods began in June, facilities already stretched by the COVID-19 pandemic started to run out of lifesaving medications altogether, said Anmol Mohan, a recent medical school graduate who began investigating after ARV shortages were reported during the pandemic.

“Patients didn’t have lifesaving medicines,” she said. “People had to travel, to take the whole day off and then the medicines weren’t there.”

The private market became the only source for such medicines, she said, but at prices that were out of reach of many patients. That left people in danger of developing resistance to the treatment and of falling dangerously ill.

This article is free to read - just register or sign in

Access news, newsletters, events and more.

Join usSign inPrinting articles to share with others is a breach of our terms and conditions and copyright policy. Please use the sharing options on the left side of the article. Devex Pro members may share up to 10 articles per month using the Pro share tool ( ).

Andrew Green, a 2025 Alicia Patterson Fellow, works as a contributing reporter for Devex from Berlin.