The Future of Education: It's coming, but will it get here fast enough?

As the world's economy embraces new technologies, the global education sector badly needs to transform itself to meet fresh challenges. So far it has lagged behind, but there are signs that it's catching up — and funding is following. Devex Editor-in-Chief Raj Kumar sends this dispatch from the Global Education & Skills Forum in Dubai on the radically shifting education landscape.

DUBAI — Education has long been notoriously slow to change. Most classrooms around the world look scarcely different than they did a century ago. But as the World Bank’s education lead Harry Patrinos told Devex at the Global Education & Skills Forum in Dubai, "the race is now being led by technology, and education is having trouble keeping up.” With automation and artificial intelligence likely to cut off the traditional path to development for many countries, which has included employing large numbers of workers in low-skill manufacturing, education systems simply aren’t ready. Take India, itself a global leader in advanced technologies. Between 50 and 80 percent of its young college graduates are literate and numerate — but still considered “unemployable.” With 1 million young people entering the workforce each month in India, the country will have a hard time developing and eradicating poverty without a fundamental transformation of its education system. That transformation is not coming quickly. But, at what is billed as the Davos of global education, more than two dozen education leaders and experts told Devex that it is in fact coming. And, they said, global development leaders and organizations can play a key role in this slowly emerging but essential trend. For one thing, experts told Devex that global attention to the education crisis is growing. So too is attention at the country level. And — perhaps most importantly — funding is following. The Global Partnership for Education’s replenishment seemed disappointingly low to some — raising $2.3 billion when the goal was $3.1 billion. But those relatively modest sums were used to incentivize governments to commit an additional $30 billion in domestic spending for education. As Action Aid’s David Archer pointed out, 97 percent of education funding will have to be raised at the country level, so this is a huge step in the direction of long-term financial sustainability for education systems. Education chiefs at the World Bank, African Development Bank, and Inter-American Development Bank all told Devex that they are increasing their financing for education reform in varying areas. For the World Bank, early childhood education is a growing priority, with Patrinos indicating to Devex that lending in this area is likely to grow to as much as $2 billion per year over the next three years (that’s versus $3 billion lent for early childhood education during the entire first 12 years of this century). For the African Development Bank, the focus area for growing investments is science, technology, and innovation skills, especially for students between lower secondary and higher education. The Abidjan-based bank even broke the news to Devex that it is creating a multi-donor trust fund to specifically target this area. The Inter-American Development Bank revealed to Devex the coming release of a significant report — five years in the making — that details how the status of the teaching profession can be improved. The solution, it will say, includes building a more merit-based pay system for teachers and emphasizing intensive on-boarding during the first three years of a new teacher’s tenure. The bank will support these policy reforms through its lending. Wendy Kopp — who founded Teach for America and, more recently, its global cousin Teach for All — told Devex that global education is decidedly not “stuck” and in fact “we are having a different discussion than five years ago.” In India, education entrepreneur Vandana Goyal said that new discussion is playing out in the form for a “seismic shift” in public interest in education. India’s Companies Act, which mandates that large companies donate 2 percent of pre-tax profits to corporate social responsibility initiatives, has resulted in new funding to education, even as government spending on education remains low and has even gone down this year. The shifting conversation around education is being driven not just by more urgency and attention but also by a focus on learning outcomes, as opposed to simply measuring inputs such as budgets and teacher pay. And educational technologies — so called edtech — is enabling that focus. In India’s Hybrid Learning Program, Rebecca Winthrop of the Brookings Institution told Devex that kids who watched Hindi educational videos that were pre-loaded onto sturdy offline tablets improved their test scores, from this relatively simple after-school intervention. A similar program in South Sudan called Can’t Wait to Learn targets internally displaced children who have never attended school. Through adaptive learning games, Winthrop says, those children are successfully gaining literacy and numeracy skills based on the curriculum of the South Sudanese government. Winthrop also told Devex about how in Brazil’s Amazonas state — a remote and difficult to access part of the country — a new system of secondary schools is relying on distance learning. “Lecturing teachers" from Amazonas with the right academic content expertise are teaching via two-way video link to 1,000 classrooms at a time. Meanwhile, “mentoring teachers” are facilitating the classroom-based learning, especially around "21st century skills" such as collaboration and problem solving. Tech-enabled or not, reforms like that won’t be possible without leaders pushing them through — a theme many conference participants came back to and an area where NGOs have an important role to play. Vikas Pota, the chief executive of the Varkey Foundation, which puts on this annual gathering, now in its sixth year, emphasized the need to “increase the political capital of the education minister.” Devex spoke with education ministers, including Ghana’s Dr. Matthew Opoku Prempeh, who, as a politician with former presidents in his family tree, knows a thing or two about political power. His focus is on using some of the country’s oil windfall to fund public education and reduce dependence on foreign aid — part of what Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo has called his “Ghana Beyond Aid” agenda. Prempeh emphasized to Devex that the president’s agenda is not about turning away from development donor partners, but rather moving toward sustainable models that rely less on foreign funding and more on domestic resources. Controlling your own budget is itself a kind of political capital. South Sudan’s education minister Deng Deng Hoc Yai was in attendance too. He had previously told Devex of ambitious plans to use education as a tool for peace in his war-torn country, and he evinced optimism in Dubai as well, even as more than half of school age South Sudanese children are out of school. The challenge for South Sudan, and for many other places facing humanitarian disaster, is that education is often the lowest priority among the humanitarian interventions. That flies in the face of what parents in conflict zones want for their children, says ICRC’s Patrick Youssef. They are placing a stronger emphasis on education, especially given the protracted nature of many of the violent conflicts around the world. But without more global urgency, education may well remain where it is now: just 2 percent of global humanitarian spending goes to education. Argentina’s former education minister and now national senator Esteban Bullrich shared with Devex a story of why building political capital to generate that kind of urgency is so hard. With Argentina soon to take up the rotating presidency of the G-20 from Germany, Bullrich lobbied President Mauricio Macri to convene the first-ever meeting of education ministers from the G-20 in an effort to increase global attention and prioritization for education. Their request to Germany to host the first such ministerial was denied in writing, with the German government indicating that such a meeting would be “a waste of time.” Now, with Argentina holding the presidency of the G-20, Bullrich will host the first such meeting in history. It’s progress, but perhaps not at the pace the world needs. As Goyal told Devex, “a system that’s been neglected for some many years will take time to fix."

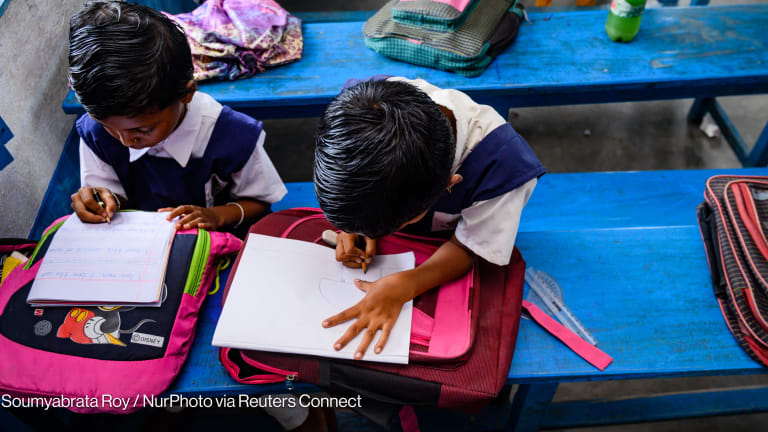

DUBAI — Education has long been notoriously slow to change. Most classrooms around the world look scarcely different than they did a century ago. But as the World Bank’s education lead Harry Patrinos told Devex at the Global Education & Skills Forum in Dubai, "the race is now being led by technology, and education is having trouble keeping up.” With automation and artificial intelligence likely to cut off the traditional path to development for many countries, which has included employing large numbers of workers in low-skill manufacturing, education systems simply aren’t ready.

Take India, itself a global leader in advanced technologies. Between 50 and 80 percent of its young college graduates are literate and numerate — but still considered “unemployable.” With 1 million young people entering the workforce each month in India, the country will have a hard time developing and eradicating poverty without a fundamental transformation of its education system.

That transformation is not coming quickly. But, at what is billed as the Davos of global education, more than two dozen education leaders and experts told Devex that it is in fact coming. And, they said, global development leaders and organizations can play a key role in this slowly emerging but essential trend.

This story is forDevex Promembers

Unlock this story now with a 15-day free trial of Devex Pro.

With a Devex Pro subscription you'll get access to deeper analysis and exclusive insights from our reporters and analysts.

Start my free trialRequest a group subscription Printing articles to share with others is a breach of our terms and conditions and copyright policy. Please use the sharing options on the left side of the article. Devex Pro members may share up to 10 articles per month using the Pro share tool ( ).

Raj Kumar is the President and Editor-in-Chief at Devex, the media platform for the global development community. He is a media leader and former humanitarian council chair for the World Economic Forum and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. His work has led him to more than 50 countries, where he has had the honor to meet many of the aid workers and development professionals who make up the Devex community. He is the author of the book "The Business of Changing the World," a go-to primer on the ideas, people, and technology disrupting the aid industry.