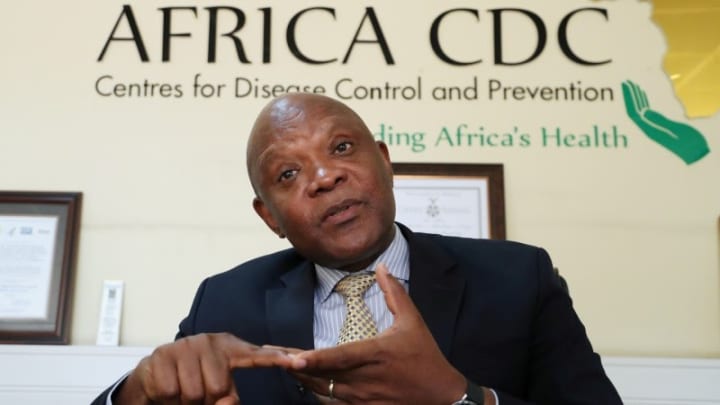

NAIROBI — Last December, John Nkengasong, director at the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, watched events unfolding in China with concern — long before the rest of the world had turned its attention to what was then just a mysterious outbreak of atypical pneumonia.

“I remember being in the United States during the Christmas break and reading these stories about Wuhan and getting worried that this was going to hit us,” he said.

Weeks later, when there were still only 200 known cases of COVID-19, he wrote an article calling on African nations to gear up for any eventual spread of the coronavirus to the continent.

The first problem facing Africa was the continent’s lack of capacity to diagnose the virus. In early February, the Africa CDC arranged for representatives from 16 African nations to travel to the Institut Pasteur de Dakar in Senegal to learn how to test for the new coronavirus.

But there was no reagent — a critical component of the tests — anywhere on the continent. Nkengasong ordered the reagent from Germany and anxiously followed the tracking number of the package, hoping it would arrive in time to train the group. Luckily, it did.

Days later, Africa had its first case.

What would then unfold was a series of seemingly impossible, gargantuan tasks. Launching a pandemic response with only two laboratories on the continent able to test for the virus and with African nations unable to buy reagents, despite having the funds.

“The collapse of global cooperation and a failure of international solidarity have shoved Africa out of the diagnostics market,” Nkgengasong wrote in April.

At the same time, countries needed support, but movement restrictions largely prevented the Africa CDC’s team from traveling, while global hoarding of personal protective equipment left health workers across the continent without basic protections.

Despite these odds, the Africa CDC and its partners have managed an effective continentwide response involving initiatives such as the pooled procurement and distribution of tests, strengthening laboratory capacity, building structures to increase the number of clinical trials, and working to lay the groundwork for the rollout of a vaccine.

While the international community feared the worst for Africa, the continent has fared far better than many parts of the world in terms of confirmed cases, deaths, and overwhelmed health facilities.

Building from the ground up

Nkengasong described the series of events that led him to a career in public health as accidental.

“I've always been an accident of life where you jump into an opportunity, you make maximum use of it, and then you grow,” he said.

It all started one afternoon in 1988, as a biology intern at the University of Yaoundé in Cameroon. Nkengasong was deeply engrossed in his research examining the prevalence of hepatitis B among pregnant women when he heard a knock at the door of the lab. He was the only person in the lab at the time; his colleagues had gone on their lunch break, but he stayed behind, curious about the outcomes of the research.

It was microbiologist Peter Piot, who would later become executive director of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. In town for a conference, he decided to visit the lab. Impressed by the drive of the young intern, Piot connected him with a scholarship at the Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp.

In Belgium, Nkengasong pursued a master’s and a Ph.D. — his doctoral research was the first to characterize the genetic diversity of HIV in Africa. He was later named the first African head of the institute’s biology lab.

“I'm not sure I knew what I was doing. I was barely 34, with those kinds of responsibilities,” he said. “And I grew in that process.”

Another life-changing moment happened in the mid-1990s. During his routine morning read of the latest scientific journals at the library in Antwerp, he saw a job posting in The Lancet for a virologist position in Côte d'Ivoire at the field station of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He left his job to build a lab from scratch, turning it into one of the most sophisticated HIV labs in sub-Saharan Africa at the time.

It was one of the first laboratories in Africa to culture the human immunodeficiency virus, map out its genetic subtypes extensively, and start describing antimicrobial resistance to HIV treatment. He led award-winning clinical trials that examined strategies for reducing the transmission of HIV from mother to infant. Côte d'Ivoire was also one of the countries to pilot the rollout of HIV drugs in Africa under his leadership.

When asked about his time in Côte d’Ivoire, Nkengasong described it as “perhaps my best period of life.”

“It was really a very fascinating period of public health practice on the continent at the time,” he said.

“[Vaccine distribution is] a challenge that we must bring ourselves to, because that's the only way we are going to come out of the pandemic.”

— John Nkengasong, director, Africa Centres for Disease Control and PreventionBut civil war broke out, and the U.S. CDC evacuated him to its headquarters in Atlanta. There, he became one of the founding leaders developing the laboratory program for the U.S. President's Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief, where he worked to strengthen laboratory capacity across Africa. His program was the largest and most funded program within the U.S. CDC’s HIV division.

A massive Ebola outbreak then hit West Africa in 2014, exposing the continent’s weaknesses in outbreak response and leading to an accelerated push for the creation of the Africa CDC.

“I really saw the way the continent struggled to manage Ebola in West Africa,” he said. “It was heartbreaking.” Nkengasong left his job to serve as the founding director of the Africa CDC.

During his first year in the role, he didn’t have an office. He floated around the African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with only his laptop, working wherever he could find an open spot.

“I didn't have a secretary; I didn't have anything,” he said.

The institute launched with a ribbon-cutting ceremony in early 2017. “I remember standing there and watching the whole ceremony … and wondering if I made the right decision,” he said. “How would this work?”

But he stayed on, centering his vision for the Africa CDC on disintegrating the silos that have long existed in Africa around managing diseases. The agency created frameworks in areas like surveillance, laboratories, information systems, preparedness, and response. He hoped that with this foundation, the Africa CDC could fight any disease.

Except in Antwerp, Nkengasong never stepped into a position that had just been vacated. Instead, he has always been building something from the ground up.

“It has been a fascinating journey,” he said.

‘You just have to swim’

To Nkengasong, the past year has felt like a blur. “It seems like my mental clock stalled in January,” he said.

“I don't think that anyone is prepared to do this,” he added. “It’s like throwing you in the middle of an ocean or a swimming pool, and you just have to swim.”

While a lot has improved since the West Africa Ebola outbreak in terms of the response to localized outbreaks, COVID-19 laid bare the continent’s weaknesses in responding to pandemics, he said. A key issue is the continent’s overdependency on countries abroad for its health security needs, including the limited manufacturing capacity.

“Look at the gymnastics that we did with the diagnostics,” he said. “Never again should we rely on Germany for reagents.”

He also sees a need to build up the capacities of national public health institutes, the health workforce in all countries, and the clinical trial capacity, and he wants African researchers to take the reins in research and development of future vaccines.

And as the pandemic wears on, the major task ahead, he said, is the equitable and timely distribution of vaccines.

“It’s a challenge that we must bring ourselves to, because that's the only way we are going to come out of the pandemic,” he said.