The reluctant nonprofit founder

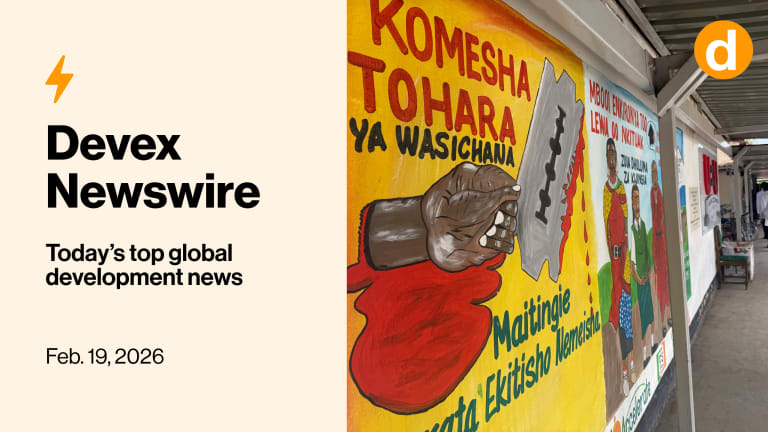

A chance volunteer experience eventually led Julia Lalla-Maharajh to found her own nonprofit to combat female genital cutting. She shares her journey from corporate advocacy expert to Orchid Project founder with Devex.

Julia Lalla-Maharajh was looking for a change from her corporate career — though she wasn’t quite sure how to go about it. Soon after, she chanced upon an opportunity during a Voluntary Service Overseas event in London, where she was pleasantly surprised to learn her advocacy skills would translate to work abroad. Initially she viewed volunteering as a short-term distraction from her corporate engagements, but that changed after she embarked on a six-month volunteering stint in Ethiopia, where she realized the magnitude of the problem of female genital cutting, the ritual removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. The practice can be found in 30 countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and among migrant communities in Europe and the United States. She returned to London feeling determined to fight the practice. Her resolve later led her to Davos, where she shocked friends by “talking about vaginas” at the World Economic Forum, then to Senegal and Gambia to witness how women are spearheading work to end FGC in their own communities. Finally, her passion led her to found the Orchid Project, a nonprofit focused on raising awareness about FGC and on advocating for resources to end its practice. Here’s an excerpt from Devex’s conversation with the CEO and founder of the Orchid Project, edited for clarity and length: What were you doing before you became involved in anti-FGC work? I was director of transport at an organization called London First. I ran a big thing called Campaign for Crossrail, a 17 billion pound ($21.2 billion) rail system across London, which is now being built. I was very much into infrastructure and policy and trying to work with all the different organizations to take that project through Parliament, get a bill, get it funded and get work to start on it. That’s quite a huge jump! I’d spent 15 years in the corporate world, and had decided I wanted to do something completely different with my life, but had no idea what. Completely by chance, I went to a VSO event. I always thought that they would need doctors, nurses, teachers, and my background had been in communications and transport policy, totally unrelated. But I was pleased and surprised to learn some of my skills such as advocacy were needed around the world. I very quickly got a role in Cambodia to run a project called Valuing Teachers, which was trying to look at the whole systemic issue around teacher supply and demand in Cambodia. I did that for six months, and then I reapplied under the same project in Ethiopia. It’s there you learned about FGC? I was reading Lonely Planet one day, and there was a little bit of boxed text about “a scream so loud it would shake the world.” But interestingly, even with the deep dive I’ve done into the background of Ethiopia, it hadn’t really come to consciousness that 75 percent of all women and girls are cut in Ethiopia. And once I read that, I started to think OK, this means of all the women I’m working with — I roughly worked with 20 women — that means 15 of them may have gone through this practice. What did you do next? Knowing I couldn’t walk in and just ask them about FGC, and realizing that it’s a taboo subject, was really difficult. What I did instead was I started reaching out to gender advisors and Ethiopian activists in my spare time, and my first question was: “I’m a Londoner, do I have a right to even talk about this issue?” And I got the most incredible endorsement from every Ethiopian and activist I worked with, who basically said: This is a human rights issue; none of us can look away from a human rights issue. But how did you start talking about FGC? One of the key issues around taboo stuff is, because it is so complex, we make it hard for people to walk toward it. And by looking away, what we do is just allow it to continue. [But when] I was in Lalibela in the north of Ethiopia, I met these two little girls, and they were trying to sell me souvenirs and saints knuckles from 2,000 years ago that were obviously just bits of stone. And I had this very, very clear moment of thinking I want to go talk to their parents and see if there’s any way that they will not be cut. Suddenly I was full of these thoughts that I’m going to rescue these two girls. I’ll pay for their education. I’ll support them for the rest of my life. But I didn’t have the language, I didn’t have the legitimacy, I didn’t have any way of rescuing the two girls. It was just impossible. And I knew I had to walk away from those two girls, but I made a vow to myself that moment that I would do whatever I could to end female genital cutting. That for me was my Damascus moment where I feel I stepped through a gateway to something different in my life, and thank goodness I did, because that rescuer syndrome comes in very quickly, that impulse. So you went back to London and set up the Orchid Project? The last thing in the world I wanted to do was set up an organization. The next stage in the journey was to go back to London. I started knocking on doors of NGOs and others because I thought, look, everyone will be working on this; they’ll have a response. To my shock, people have projects here and there, but really there was no compelling campaign. What was most shocking to me was there was really no theory of change around ending FGM. So you went back to do transport work? An incredible thing happened: I entered a competition asking for one urgent human rights cause. And I won this competition, and the prize was to go to the World Economic Forum and make the case to the audience at Davos. So I found myself with three days’ notice going to Davos [where] they put on a whole debate for me, and I had a white badge, which meant I can access all areas. I spoke with former President Bill Clinton and Melinda Gates. I had gone to Davos full of trepidation. People had said to me: you can’t talk about vaginas at the World Economic Forum, and my whole pitch was we mustn’t marginalize issues like this. What we must do is look at them in a socio-economic-political-holistic way. Part of this issue with FGC is it’s orphaned and taboo; it has no champions. Far from people turning away and not wanting to hear, I found everyone I engaged with gave me time, wanted to listen, wanted to understand. You were fired up again. That was an extraordinary moment. But two things: one was I learned more about the work being championed by UNICEF and UNICEF’s theory of change, and second, a number of people said to me: “You must go to Senegal and see the change that’s happening there.” So after a year, in January 2011, I went to Senegal. I was invited there by an organization called Tostan, and I volunteered there and stayed for two months. I was able to see first-hand the change that was happening on the ground. At the first declaration ceremony I went to — the culmination of an intensive 30-month work with the entire community — I just sat there with tears running down my face because I witnessed communities making a choice in such an incredibly strong way that they will no longer cut their daughters. It was so embedded and so powerful, and the theory behind it, that posits FGC as a social norm, finally, I understood. What did you understand? I could never grasp why parents cut their daughters, and I knew it wasn’t an active mutilation torture, barbaric, which is this language that comes up with regards to this issue, because I’d lived with Ethiopian families and I knew they loved their daughters. So trying to understand why they are trapped in having to make this horrendous decision, this [immersion] gave me my first insight into that understanding that a social norm is a code that’s been held in place and has been there for centuries and is often never even talked about. How did that understanding inform your work against FGC? Having seen this incredible program, I went back to London and decided that I would try to set up Orchid Project, because what I saw was three main things: One was how to communicate this theory of change more widely based on the evidence that exists about how change is happening. Second was how to support community-led organizations that are doing the work at the grassroots level. And third, how can we really move the big leaders within the development community and wider, because as all know now, there are huge horses at play — whether that’s the multilateral world, or the U.N. world, or the African Union, or all of these players who have a voice. So I set up Orchid with those three things in mind: to support grassroots work, to communicate the issue, and to advocate for more resources. And that was in April 2011. But you said earlier you never wanted to start your own organization? When I was in Senegal and Gambia, I was talking with the women who were obviously cut, but their communities chose to abandon the practice years ago, and now they volunteer to go out. They walk — or get a horse or carts — to their surrounding communities who are still practicing, and they are spreading the word about why they chose to stop cutting their daughters. And then I remembered thinking, “OK, I’ve been saying there’s no theory of change. But now I can see a theory of change. What more do I need to be shown by the world to step up and support others?” I was also with this incredible woman called Marieme Bamba, and I remembered thinking I’ve got to have this woman’s back. And I think if she is at the forefront of this change, here’s me in this incredible country that’s championing women and girls with organizations such as [the Department for International Development]. If I can’t anchor back to this experience and try and make this work, then I have no right to criticize others for not doing it. Devex Professional Membership means access to the latest buzz, innovations, and lifestyle tips for development, health, sustainability and humanitarian professionals like you. Our mission is to do more good for more people. If you think the right information can make a difference, we invite you to join us by making a small investment in Professional Membership.

Julia Lalla-Maharajh was looking for a change from her corporate career — though she wasn’t quite sure how to go about it. Soon after, she chanced upon an opportunity during a Voluntary Service Overseas event in London, where she was pleasantly surprised to learn her advocacy skills would translate to work abroad.

Initially she viewed volunteering as a short-term distraction from her corporate engagements, but that changed after she embarked on a six-month volunteering stint in Ethiopia, where she realized the magnitude of the problem of female genital cutting, the ritual removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. The practice can be found in 30 countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and among migrant communities in Europe and the United States.

She returned to London feeling determined to fight the practice. Her resolve later led her to Davos, where she shocked friends by “talking about vaginas” at the World Economic Forum, then to Senegal and Gambia to witness how women are spearheading work to end FGC in their own communities. Finally, her passion led her to found the Orchid Project, a nonprofit focused on raising awareness about FGC and on advocating for resources to end its practice.

This story is forDevex Promembers

Unlock this story now with a 15-day free trial of Devex Pro.

With a Devex Pro subscription you'll get access to deeper analysis and exclusive insights from our reporters and analysts.

Start my free trialRequest a group subscription Printing articles to share with others is a breach of our terms and conditions and copyright policy. Please use the sharing options on the left side of the article. Devex Pro members may share up to 10 articles per month using the Pro share tool ( ).

Jenny Lei Ravelo is a Devex Senior Reporter based in Manila. She covers global health, with a particular focus on the World Health Organization, and other development and humanitarian aid trends in Asia Pacific. Prior to Devex, she wrote for ABS-CBN, one of the largest broadcasting networks in the Philippines, and was a copy editor for various international scientific journals. She received her journalism degree from the University of Santo Tomas.