When the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the world’s largest private foundation, announced in 2018 that it would invest $68 million over four years into global education, some asked: Why not more?

The figure pales in comparison to the foundation’s global health grant-making, which averages $780 million annually. It has also committed $1.75 billion in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some experts wondered whether the Gates Foundation was discouraged by its experience funding education in the United States, where a project to improve teacher effectiveness failed. Others figured the foundation might be daunted by the complexity of the sector. While some global health challenges may be solved by pills, bed nets, or vaccines, many interventions in education rely on human interactions between students and teachers.

Since launching its global education strategy, the foundation has paid out nearly $50 million and has expanded its average annual budget to approximately $25 million. Its outgoing director of global education defends the decision to limit its investment.

In-depth for Pro subscribers: Q&A: The Gates Foundation's evolving global education strategy

In 2018, the Gates Foundation said it would invest $68 million in global education. The outgoing head of global education strategy discusses what the foundation has learned since then.

“Many people fantasize about the idea of Gates being the deus ex machina in the field and coming in with lots and lots of money,” said Girindre Beeharry, who recently announced he is stepping down and now serves as an adviser to the foundation. “That’s not the case.”

While the foundation has determined it has a role to play in education, that does not necessarily mean it will be making a more significant financial investment in the sector, Beeharry told Devex. Despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, philanthropy cannot be a backstop for national spending or aid budgets in the education space, he said.

With a search underway for Beeharry’s successor, the foundation is exploring what’s next for its work in global education.

Prioritizing foundational learning

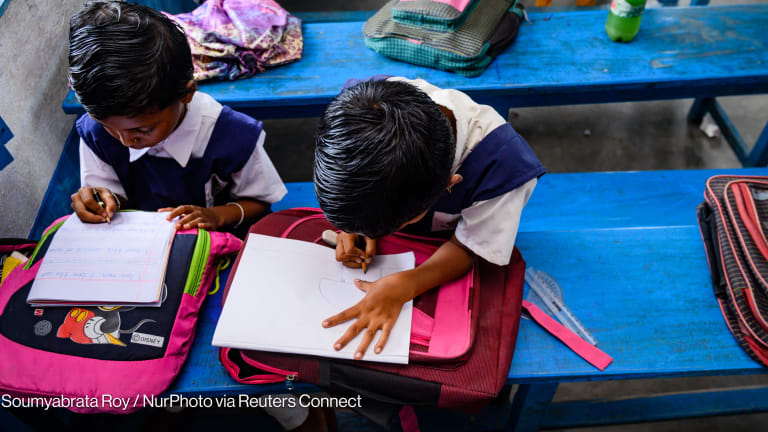

The Gates Foundation launched its global education strategy in response to the problem of millions of children attending school but learning very little. In low-income countries, 9 in 10 children cannot read with comprehension by age 10, a phenomenon the World Bank calls “learning poverty.”

Initially, the foundation’s strategy focused on what it called “global public goods,” or making data on learning outcomes comparable across countries to inform local education policy in the regions where it focused — namely, South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

For example, it granted the World Bank $2.6 million to develop a dashboard to deliver governments data on what is happening at the classroom level. When it launched, some experts questioned whether the tool — which draws on existing data and gathers new data via surveys, classroom observations, teacher assessments, and more — was really what countries needed most.

Meanwhile, the Gates Foundation ran into unexpected challenges with its overall approach. For one, it did not see the kind of demand it expected for information that might close the gap between attendance and learning, Beeharry said.

“The sense I was getting was there was no sense of urgency behind the work. And therefore the demand for the public goods was, ‘OK, nice, we’ll accept it, but it doesn’t change anything,’” he said.

Beeharry outlined some of these frustrations in a recent paper in the International Journal of Educational Development. He called on the education sector to prioritize a few key goals – in particular, boosting foundational literacy and numeracy, or FLN; monitoring progress to achieve those goals; and holding itself accountable for improving results. Beeharry said the paper serves as a preview of the direction the foundation’s strategy is likely to head, with investments that extend beyond global public goods and into advocacy and accountability.

Gates Foundation COVID-19 commitment reaches $1.75B with latest pledge

The Gates Foundation commits an additional $250 million toward COVID-19 vaccine research and development. But philanthropy is not a long-term solution, CEO Mark Suzman tells Devex, saying, “We’re a stopgap, we’re an accelerator, we’re a catalyst."

Finding its place in the global education architecture

Beeharry and his team spent the past few years researching whether the global education architecture is effectively promoting learning in low-income countries, what is standing in the way of progress, and how to address those problems, said Lant Pritchett, research director for the Research on Improving Systems of Education program at the University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government.

“I think their strategy was, ‘Let’s get engaged in the sector in a way that puts us at the table in a research sense, but we don’t yet have to make hard decisions about who, where, what,” he said.

Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic is having a devastating impact not only on learning but on government spending on education, said Kenneth Russell, education specialist at UNICEF.

“This is not the time to maintain pre-COVID commitments or cut expenditures,” he said in an email to Devex. “We do advocate for donors, Gates Foundation included, to increase and diversify their education funding.”

Still, even without an increase in funding levels, the Gates Foundation can play an important role in global education, Russell said.

“The Gates Foundation can continue to be a major influence in global education through support for innovations to improve learning at scale including use of technology to enable access for the most marginalized, helping to strengthen collaboration among the various donors in the sector, and influencing governments to maintain their investments in education,” he said.

If the foundation were to invest as much money in education as it does in global health, the only way to spend such vast amounts would be to support the Global Partnership for Education, the existing mechanism to fund countries’ education plans, or to finance projects in particular countries, Pritchett said.

That would lead to questions about “why this and not that, why here and not there” — more comprehensive alternatives that the foundation is not in a position to consider, he added.

Beeharry’s recent paper reflects why the foundation does not see a reason for it to augment the existing global education architecture, Pritchett said.

“I don’t think any of its fundamental premises of not devoting more money to this has been challenged,” he said.

Working with willing countries

Since launching its global education strategy, the Gates Foundation has expanded its portfolio to directly improve reading and math outcomes among children in early grades in India and sub-Saharan Africa. Last month, for example, it provided a $14.7 million grant to India’s Central Square Foundation, which works to ensure early reading and math skills for all children in the nation.

The Gates Foundation is also focusing its efforts on countries that are already convinced of the importance of FLN.

“If you don’t really care about FLN and I bring you a tool that tells you FLN’s not working, it’s not going to work for you,” Beeharry said.

In August, the foundation provided the World Bank with an $11.2 million grant in support of its Foundational Learning Compact trust fund. Its support is directed toward an Accelerator Countries program that will “support willing countries,” Beeharry said in a blog post about the effort. Five countries will build on evidence of what works —such as teaching children to read in a language they understand — to improve learning outcomes.

This effort is an example of the Gates Foundation supporting work on a country level, where ministries of finance decide how to spend resources.

“That’s where the game has to be played,” said Jaime Saavedra, global director of education at the World Bank and former minister of education in Peru.

The question then becomes how to expand these initiatives beyond the willing countries.

“The right intervention or design is a good step, but then the next thing you need to have is a good implementation capacity and political will,” Saavedra said.