A new model for private sector partnership – and its implications for donors

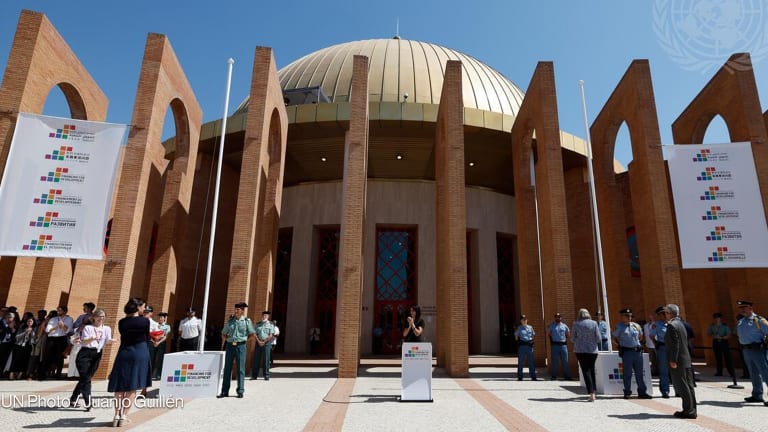

<p>International donors such the Japan International Cooperation Agency are increasingly courting the private sector to boost development – including at last month’s Fourth U.N. Conference on the Least Developed Countries in Istanbul, writes Thomas Feeny in a guest opinion for Devex.</p>

Last month, I visited Istanbul for the Fourth U.N. Conference on the Least Developed Countries – the meeting of governments, businesses and civil society organizations to map out the specific challenges faced by the world’s poorest nations. This takes place every ten years. I was there on behalf of the Japan International Cooperation Agency, the international aid and development arm of the Japanese government, whose U.K. office I recently joined. Having worked in international development for the last ten years, the conference represented a great opportunity to apply my increasing knowledge of JICA’s operations to the broader debates with which I have long been familiar. Yet as I took my place amongst the 11,000-strong crowd of delegates, it was clear that an unparalleled sense of optimism was now breathing new life into the old arguments. New development orthodoxies were taking shape and participants were visibly energized. Though progress across the LDCs has been slower and less dramatic over the last decade than the 2001-2010 Brussels Program of Action had envisaged, the significant growth in some African economies, and the rapid advance of the BRIC nations, have given rise to a tangible feeling that the balance of the global economy is now firmly tilting to new parts of the planet, with dramatic new consequences. >> Global Development: What You Need to Know For the first time, many of the leaders that had traveled to Istanbul from the LDCs were able to proudly outline legitimate – if long-term – plans to become “frontier markets” and ultimately “emerging markets” themselves. It was particularly interesting, in that sense, to be attending the private sector “track” of the conference – absent from the previous conferences in this series, and yet a clear focus of attention for delegates and organizers alike. Not only does this mark a definite shift in attitudes towards embracing the private sector’s role as a development actor, it also paves the way for a wealth of new approaches, partnerships and possibilities. Many of these are included in the 2011-2020 Istanbul Program of Action adopted by the conference, and many more will no doubt emerge from the 4th High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness taking place in Busan, South Korea, at the end of this year. But what implications will this paradigm shift in development have for the strategy and operations of the more “traditional” actors – including NGOs and government agencies such as JICA – that have been historically central to the aid and development agenda? Like many of our fellow donor agencies, JICA is not unusual in having partnered with many private corporations over the last decade to combine poverty reduction with corporate social responsibility, and we have had a central “Office of Private Sector Partnership” advising on these strategies for some time. What is clear is that private sector engagement among government agencies is now surging ahead on a wave of contemporary interest, demanding new models of partnership and collaborative governance. Following the creation of a private sector department in January this year, the U.K. Department for International Development released its strategy a few weeks after the conference conclusion, heralding the private sector as “the engine of development” with the aim of “bring[ing] private sector ideas, innovation and investment into the heart of what we do.” JICA’s approach has been more moderate by comparison, gradually building the foundations of a comprehensive strategy through a range of private sector partnerships in areas such as HIV/AIDS prevention, regulation reform, and “development for trade” initiatives such as investment-friendly special economic zones, or SEZs. In addition, JICA provides loans and technical expertise for a significant number of infrastructure projects, including road, bridge and port developments, the extension of energy grids and initiatives such as the innovative One Stop Border Post program, which facilitates the flow of goods across borders by streamlining customs checks and improving regional trade and transport integration. Despite peer pressure within the donor community to abandon infrastructure in favor of “hot topics” such as governance, JICA has demonstrated a longstanding commitment to such projects, which, interestingly enough, are now recognized as essential precursors to the attraction and sustainable involvement of private sector groups in developing countries. With 33 of the 48 LDCs being in Africa, this will no doubt constitute fertile training ground as public-private partnerships proliferate. While a continent-wide strategy will be important, success will rest on the development of locally-tailored pilot initiatives. With the majority of its support and private sector experience understandably targeted at Southeast and East Asia, JICA is nevertheless committed to increasing its support to Africa at this time – in fact doubling it by 2012. Considerable success has also resulted from the One Village One Product initiative, in which a traditional Japanese development model has been adapted and scaled across a large number of communities in several East African countries to stimulate economic growth through the trade and export of local artisan products. All of this led me, like many other delegates at the Istanbul conference, to return home with a strong sense of hope in the face of looming failure across a number of the Millennium Development Goals. Powerful and far-reaching opportunities lie ahead for agencies such as JICA, which are in a strong position to share models of good practice at a time of great change within the development landscape. Read more international development business news.

Last month, I visited Istanbul for the Fourth U.N. Conference on the Least Developed Countries – the meeting of governments, businesses and civil society organizations to map out the specific challenges faced by the world’s poorest nations. This takes place every ten years.

I was there on behalf of the Japan International Cooperation Agency, the international aid and development arm of the Japanese government, whose U.K. office I recently joined. Having worked in international development for the last ten years, the conference represented a great opportunity to apply my increasing knowledge of JICA’s operations to the broader debates with which I have long been familiar.

Yet as I took my place amongst the 11,000-strong crowd of delegates, it was clear that an unparalleled sense of optimism was now breathing new life into the old arguments. New development orthodoxies were taking shape and participants were visibly energized.

This story is forDevex Promembers

Unlock this story now with a 15-day free trial of Devex Pro.

With a Devex Pro subscription you'll get access to deeper analysis and exclusive insights from our reporters and analysts.

Start my free trialRequest a group subscription Printing articles to share with others is a breach of our terms and conditions and copyright policy. Please use the sharing options on the left side of the article. Devex Pro members may share up to 10 articles per month using the Pro share tool ( ).

The views in this opinion piece do not necessarily reflect Devex's editorial views.

Thomas currently serves as senior program officer in the Japan International Cooperation Agency's U.K. office. He holds degrees from Cambridge and the University of London, and has worked in international development for the last 12 years for organizations including the United Nations and Save the Children.