NAIROBI — In early 2019, Kuria Weru, a 34-year old resident of Kiambu, Kenya, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, was unemployed and struggling financially. He had started an information technology company with a friend, but it was not doing well. Weru’s family advised against the arrangement, and as time went on, their concerns proved well-founded.

Weru said he knew that he needed to make a change but was torn about what to do. He wanted to speak to someone but worried that his friends would make light of the situation and that his family would say they had already warned him.

He said he had never considered therapy and did not have the money to pay for it anyway.

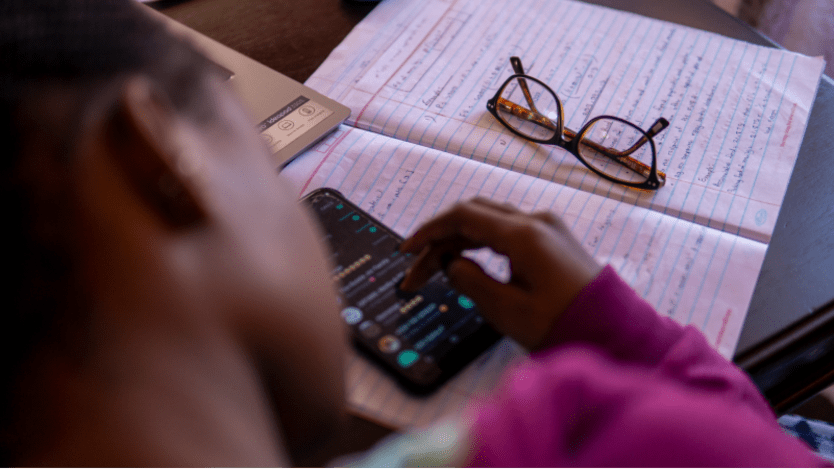

Around this time, a friend told Weru about Wazi, an online therapy service that was being piloted in Kenya and staffed by volunteers who could help him over the phone.

“He told me that the service offers a chance to have a conversation with someone who wasn’t going to judge but listen and give a different perspective of the problem one is facing,” he said.

Weru accessed the service through the Telegram messaging platform. He found it strange at first, he admitted, but he took comfort in the fact that it provided an anonymous environment. Weru accessed several Wazi sessions and said it proved very helpful.

“After the sessions, I was able to make a decision,” he said.

Weru decided to leave the startup and reconnect with a financial institution in Nairobi that had previously offered him an IT position.

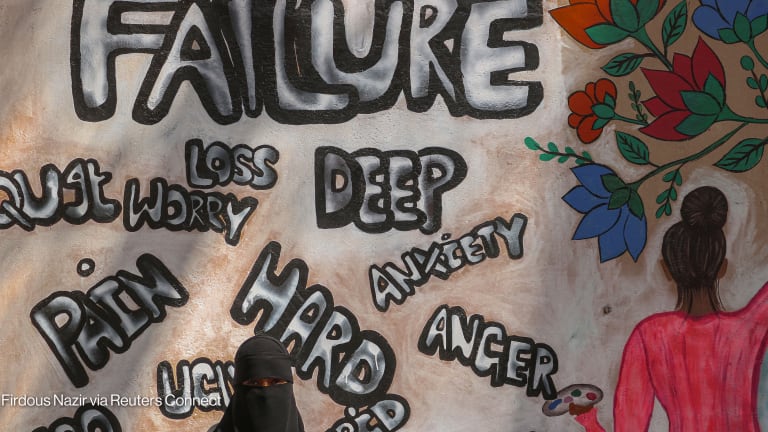

In many parts of Africa, mental health has been badly neglected and access to qualified mental health professionals is limited, leading to a large treatment gap for mental illness across the continent.

“The highest quality mental health resources are traditionally only available in urban areas, out of reach of those not physically near.”

— Alex Royea, CEO, WaziIn 2011, the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights found that up to 25% of outpatients and up to 40% of inpatients in Kenyan health facilities suffer from mental health conditions. A significant percentage of cases of these illnesses are still neglected due to stigma, which limits access to care and decreases quality of life for individuals affected by mental, neurological, and substance abuse disorders. The World Health Organization has estimated a mental health treatment gap of over 75% in many low- and lower-middle-income countries like Kenya.

Online therapy offers one potential solution to reaching more patients with mental health services, and that is what Alex Royea sought to do in founding Wazi.

“The highest quality mental health resources are traditionally only available in urban areas, out of reach of those not physically near. Through Wazi, people can just pick up their device, wherever they are, and get the support that they need,” he told Devex.

Users can access their therapy sessions through apps such as Facebook Messenger and Telegram or via voice and video calls.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, telecounseling services have mushroomed in Kenya. Veronicah Ngechu, a counseling psychologist with Wazi, said she has seen many services popping up in the country. She said she worries that since some of them use insecure channels, they may be endangering their patients with sessions that are vulnerable to hackers.

She shared that reservation when Wazi approached her to work with its team.

“That was my biggest concern. I was concerned [about] the level of safety that Wazi could provide. And this is because patients may be seeking therapy after betrayal, and therapy is their last resort. And you don’t want to fail them,” Ngechu said.

Wazi has made the protection of its user data a top priority.

“As part of maintaining confidentiality and privacy, people join Wazi anonymously. We then collect only the information that is crucial to use the service and only authorized individuals can interact with the data through secure and encrypted channels,” Royea said.

“One-on-one conversations on Wazi via video and audio calls are end-to-end encrypted. We hope to adopt even more global information protection standards in future,” he added.

Wazi also licenses its technology for use by public and nongovernmental organizations. This has seen over 10,000 people reached with mental health services over a period of six months. Wazi has partnered with five companies in Kenya so far through its employee wellness program, which provides businesses with therapy for their employees.

Ngechu said she believes digital mental health care offers an ease of access that might help reduce Kenya’s treatment gap, noting that “it has the advantage of absence of bias, provides convenience, and [multiple] modes of communication to choose from.”

Search for articles

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5