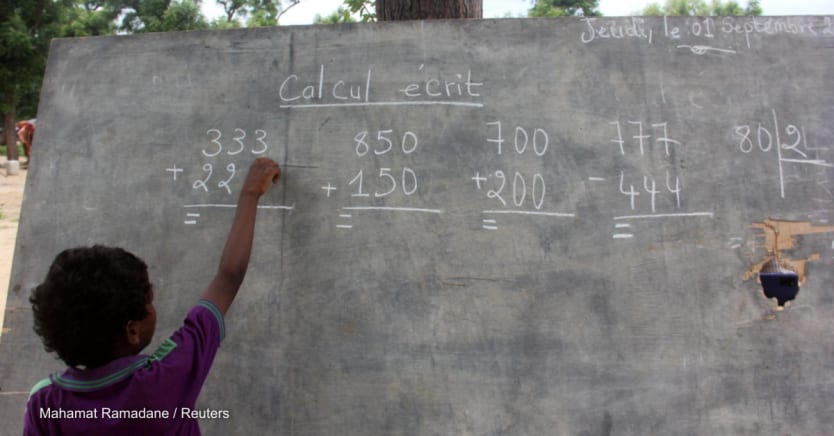

Globally, only 1 in 3 10-year-olds are estimated to be able to read and understand a simple written story, UNICEF warned recently. This represents a 50% decrease from pre-pandemic estimates.

The staggering statistics raise questions on the ability of traditional aid, which is already being sapped by inflation and shrinking foreign aid budgets by high-income countries like the U.K., to regain that learning loss.

But the International Finance Facility for Education, or IFFEd — announced as part of the Transforming Education Summit at the United Nations General Assembly this week — hopes to fill that gap.

The name of the program is complicated, but the premise is simple: Amplify education funding through cheaper loans.

How does it work?

While it’s billed as a “game-changing” new financing model, IFFEd is actually a revival of sorts from a proposal put out back in 2016. The goal is to increase education funding in low- to middle-income countries — home to more than half of the world’s children and youth — through low-interest loans from multilateral development banks, or MDBs.

The mechanism by which it works is that donor countries would back grants and guarantees to MDBs that would allow the banks to borrow more capital — which in turn would allow them to offer loans at lower rates.

Watch: The urgency and harsh truths of transforming global education

Education is key to a country's success, yet too many nations are failing to educate their children. Leonardo Garnier, a special adviser at the U.N., discusses why the upcoming Transforming Education Summit could be a "tipping point" in tackling this crisis.

The Education Commission says this model could unlock an extra $10 billion in new funding by 2030. An initial $2 billion was announced at the launch, with the first projects expected in 2023. They will focus on Africa and Asia — in collaboration with the Asian Development Bank and African Development Bank — before expanding globally.

Notably, however, the World Bank isn’t on the MDBs roster — a huge hole given the bank’s lending supremacy.

What’s the appeal?

For donor countries backing the grants and guarantees, they effectively wouldn’t need to put up capital upfront.

For MDBs, they can borrow on affordable terms to scale up lending by an estimated $4 for every $1 of guarantees they get.

For recipient countries, the benefits are obvious: loans at cheaper interest rates.

The program is particularly geared toward middle-income countries that no longer qualify for the concessional loans offered to low-income countries via the World Bank’s low-income facility known as the International Development Association.

Who supports it?

Sweden, the U.K. and the Netherlands have been at the forefront in designing IFFEd, which is backed by 100 world leaders. It’s spearheaded by Gordon Brown, the former British prime minister who’s now the U.N. special envoy for global education.

“To truly transform education, we need a fundamental shift. Business as usual will not suffice. This is why the International Finance Facility for Education is such an exciting development for our future generations,” Brown said at the announcement on Saturday.

Susannah Hares, co-director of education policy and senior policy fellow at the Center for Global Development says Brown recognizes that foreign aid is drying up — and high-income countries might not replenish it.

“His argument is that middle income countries face a fiscal cliff when they graduate out of eligibility for the World Bank’s window for the poorest countries – as Bolivia, Georgia, and Sri Lanka have done in recent years. While 11 percent of the World Bank’s concessional loans go to education, only 6 percent of its non-concessional loans do,” Hares writes in a blog post with co-authors from the Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

Who doesn’t support it?

Details on commitments are still scarce, and IFFEd is not without its detractors.

Theoretically, it would complement other funding vehicles such as the Global Partnership for Education and Education Cannot Wait, along with bilateral aid from Development Assistance Committee donors.

Critics also say IFFEd will just pile on more debt for countries already struggling with high levels of debt accumulated in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, crippling food and fuel prices, and soaring inflation.

That financial blow is partially why two-thirds of low- to middle-income countries have cut education spending since the beginning of the pandemic.

Those same factors are why high-income countries are slashing foreign aid budgets.

And this is why IFFEd’s supporters say the world needs to get creative to save its children.

“Education is a silent crisis; you don’t see the dead bodies,” Jaime Saavedra, head of education at the World Bank, told Devex in June. “It is true that we have several competing crises …[and] unfortunately at the same time … we have this other [learning] crisis and if we don’t do something it will have a gigantic impact on our future.”