BRUSSELS — A risk-averse approach from some banks, humanitarians, and governments when dealing with countries under sanctions is jeopardizing the delivery of much-needed aid, according to a senior official at the European Commission.

Michael Köhler, deputy director-general at the department for humanitarian aid and civil protection, known as ECHO, said Monday that some actors are taking a “holier-than-thou” stance.

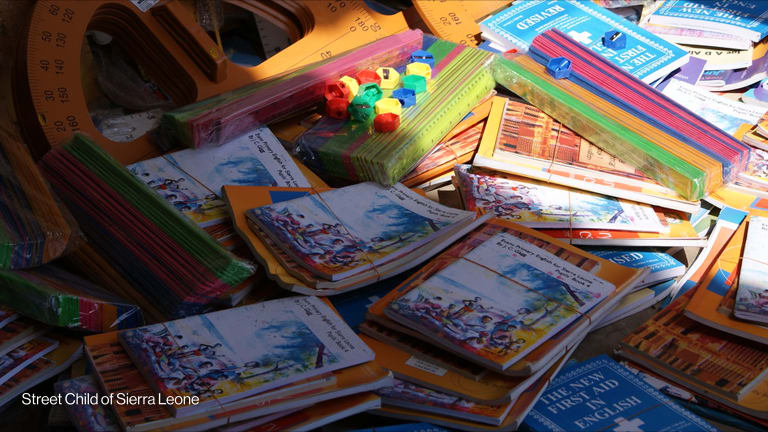

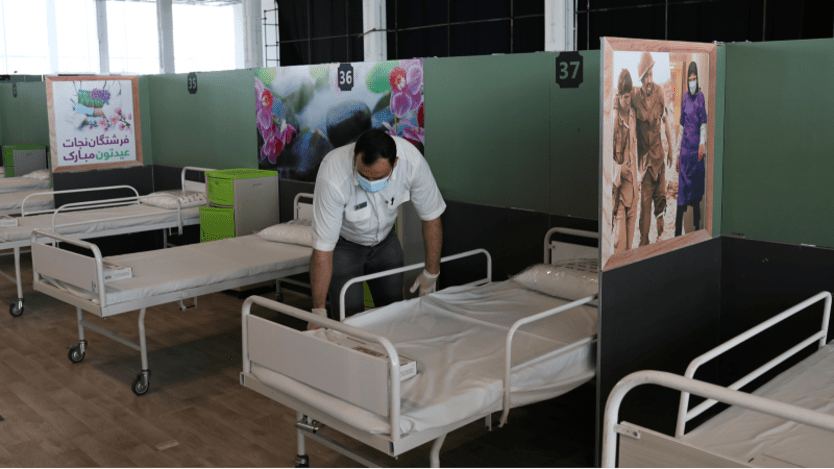

Iran, NKorea, Syria: How sanctions are hindering coronavirus response

Years of sanctions have impacted the ability of Iran, North Korea, and Syria to respond to the novel coronavirus outbreak. Experts tell us why.

Sanctions from the United Nations, U.S., or European Union usually contain an exception for humanitarian supplies, Köhler told the European Parliament’s development committee in a hearing on the bloc’s response to COVID-19. “However, what is happening is that many humanitarian operators and also banks that are transferring humanitarian funds ... are implementing so to say embargoes and sanctions where the legal text does not require that they do so.”

Köhler, an experienced bureaucrat in the EU civil service, said that as a result, the commission is reaching out to governments and banks to allay concerns that they may fall foul of sanctions if they help to channel humanitarian assistance.

“We are speaking in particular with the U.S. There is a very active dialogue on this, in order to make sure that the exemption of humanitarian operations under sanctions regimes is even more clear,” he said.

“And what we do on almost a daily basis is that we send letters to NGOs and to other major organizations implementing the aid response to reassure them and enable them to show those letters to the banks, for example, and show the banks that what these NGOs are doing — Oxfam, CARE and other NGOs — what they are doing is financed from European funds, is financed in order to set up a humanitarian response, and is therefore not affected by international sanctions regulations,” he continued.

“Whatever we do here at headquarters ... will not work if the material cannot be delivered and if the aid workers cannot reach the people in need.”

— Michael Köhler, deputy director-general, ECHOA U.S. State Department spokesperson told Devex: “We are in dialogue with interested partners, including the European Union, to make sure humanitarian aid reaches those who need it, and at the same time to make sure our sanctions programs fulfill their intended purpose, which is to constrain the ability of bad actors to take advantage of our financial system or threaten the United States, our allies and partners, or civilians.”

“As a general matter, the United States does not use sanctions to target bona fide humanitarian-related trade, assistance, or activity. Rather, we often, and in many circumstances proactively, exclude this type of activity from our sanctions programs … [We continue] to propose additional solutions to facilitate swift humanitarian assistance to those in need across the full range of U.N. sanctions regimes.”

An ECHO spokesperson did not say which countries, sanctions regimes, or banks Köhler was talking about. Spokespeople for Oxfam and CARE said their organizations were unable to comment this week, with both citing capacity constraints.

A European Banking Federation spokesperson explained it is primarily up to each financial institution to take its own risk decisions in the “complex and heavily regulated cross-border economic environment.”

The spokesperson added that “EBF is permanently engaged in a dialogue with relevant authorities to ensure that mechanisms are in place to enable financial institutions which want to do so to perform authorised transactions, in particular those related to the provision of humanitarian goods, while having legal certainty that they are compliant with the anti-money laundering requirements and EU/international sanction regimes.”

Patrick Saez, a senior policy fellow at the Center for Global Development, welcomed the commission’s communication efforts as a way to share the responsibility for managing risk with NGOs. Faced with increasingly stringent regulatory requirements after 9/11 and the global financial crisis, Saez said banks often decided that “if there was a bit of uncertainty as to the risk, they would rather not take the risk, even though the language in the sanction regime was quite clear that there is an exemption for humanitarian activities.”

In April, the U.S. Treasury issued a statement, reminding the financial sector that “reputable, legitimate organizations implement a range of risk-mitigation measures including due diligence, governance, transparency, accountability, and other compliance measures, even in a crisis.”

The statement underlined that U.S. sanctions ought not to hamper the transfer and delivery of humanitarian aid to countries including Iran, Venezuela, Syria, and North Korea.

Köhler said more attention was needed on making the terms of sanctions clearer, as well as telling various actors that they need to be “more open-minded when it comes to allowing humanitarian response.” If not, Köhler warned, “whatever we do here at headquarters and what our people in the field want to do will not work if the material cannot be delivered and if the aid workers cannot reach the people in need.”

Update, June 19: This story was updated to include additional comment.