The U.S. Export-Import Bank lives on to fight another day, albeit bruised by a divisive reauthorization battle.

Last month, Congress voted to reauthorize Ex-Im, the government agency that finances U.S. exports of goods and services — but only through June 30, 2015. The measure passed after it was tucked into a much larger spending bill that also funded the Obama administration’s Ebola response.

In a debate largely fought along ideological lines, tea party Republicans argued that Ex-Im has a history of financing politically favored companies. Advocates for Ex-Im, including the Obama administration, insisted that in the face of stiff global competition, the bank’s support is needed to sustain American businesses and jobs.

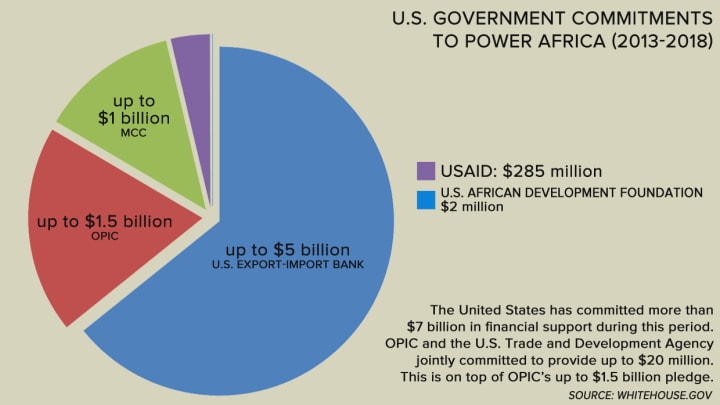

Drawing far less scrutiny and attention in Washington, however, is the reality that Ex-Im is also emerging as a key player in Power Africa, U.S. President Barack Obama’s initiative to double access to energy across sub-Saharan Africa by 2018. In fact, of Obama’s $7 billion, five-year pledge to Power Africa announced last year, up to $5 billion in financing is slated to come from the bank.

Ex-Im’s reauthorization means the bank’s outsized commitment to Power Africa — widely seen as Obama’s “legacy initiative” in sub-Saharan Africa — remains intact for now. At the same time, there remain many lingering questions about how the bank’s role in Power Africa will play out.

For one, how exactly does a U.S. export credit agency without a development mandate fit into a U.S. development initiative? How realistic and achievable is Ex-Im’s highly ambitious $5 billion financing target? Can the bank’s Power Africa commitment withstand another protracted reauthorization debate next year?

Over the course of several weeks, Devex spoke with former and current Ex-Im officials, business leaders and development experts to dig deep into these critical questions. We’ve found that while the $5 billion Power Africa target will be an uphill climb for Ex-Im, the bank does seem serious about integrating development considerations into its financing decisions.

A long way from $5 billion

In the year since Power Africa was launched, the Obama administration touted its $7 billion pledge as proof positive of its high level of commitment to sub-Saharan Africa. Billions in additional contributions from the private sector and donor community have also poured in — including the World Bank’s $5 billion commitment at August’s U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit.

What is often overlooked, however, is how relatively little of the $7 billion Obama administration commitment is slated to come as grant money from either the U.S. Agency for International Development or the Millennium Challenge Corp. The administration anticipates that the lion’s share of the $7 billion figure will come in the form of U.S. export finance from Ex-Im. That approach lines up nicely with Obama’s 2012 strategy to elevate U.S commercial ties with sub-Saharan Africa.

Former and current Ex-Im officials told Devex that the bank’s big checkbook helps explain the administration’s decision to make Ex-Im the financing juggernaut of Power Africa. Self-sustaining from its interest and fee revenues, Ex-Im imposes no maximum limit on its loans, which the bank only authorizes when there is reasonable assurance of repayment.

“The financial merits of a project — that really sets the amount that we would be comfortable with in lending to a project,” Ben Todd, senior business development officer for Africa at Ex-Im, elaborated.

Ex-Im’s single-largest authorization to date — an almost $5 billion loan in 2012 for a petrochemical complex in Saudi Arabia — nearly matches the bank’s five-year commitment to Power Africa. And, under direction from Congress, the bank has been expanding its engagement in sub-Saharan Africa over the past decade. Last year, it authorized more than $27 billion in U.S. export financing, of which $604 million was directed to the region.

Despite Ex-Im’s financial heft, however, Todd revealed that the bank has only made a “small dent” in its $5 billion Power Africa target. But he emphasized that the bank has a robust pipeline of power projects in sub-Saharan Africa waiting for a green light from developers and regulators.

“I like to say that Africa needs long-term finance and long-term patience because you know power projects are inherently complicated and so they take a lot of time,” Todd stressed.

Pressed on Ex-Im’s progress thus far toward its Power Africa pledge, Todd cited two transactions over the past year: a $17 million loan guarantee to buy steam turbines for the Azito Power project in the Ivory Coast and $34 million in loans for solar-related products that will be used in both South Africa and Spain. He also clarified that Ex-Im does not limit its participation in Power Africa to the initiative’s six focus countries: Tanzania, Liberia, Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria and Kenya.

Strikingly, Overseas Private Investment Corp. seems to be much further in fulfilling its $1.5 billion, five-year pledge to Power Africa — the second-largest commitment by a U.S. government agency after Ex-Im. Since June, the U.S. development finance institution has approved up to $300 million in financing for power projects in Kenya and Nigeria.

“The $5 billion Ex-Im component was always more fantasy than reality, but by putting such a big number out there, they hoped that more U.S. companies would come looking for trade financing.”

— Ben Leo, senior fellow, Center for Global DevelopmentWhile Ex-Im officials project confidence that the bank will make significant progress toward its $5 billion Power Africa target, outside observers believe the bank may have set its sights too high.

“The $5 billion Ex-Im component was always more fantasy than reality, but by putting such a big number out there, they hoped that more U.S. companies would come looking for trade financing,” asserted Ben Leo, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development.

By Leo’s count, Ex-Im financed only three transactions totaling $1.2 billion for Africa’s power sector between 2000 and 2013. For Ex-Im to meet its Power Africa target in 2018, then it will have to quadruple the value of transactions in just four years. The bank seems to be pinning its hopes on the prospect that over the period, sub-Saharan Africa’s improving business climate will draw more U.S. power companies, which then look to Ex-Im to sweeten the pot for African buyers.

“There is not enough activity by American companies doing that now to have that many deals presented to Ex-Im for support,” Robert Perry, vice president for international programs at the Corporate Council on Africa, said of Ex-Im’s $5 billion target. “This could change over the next 24 months as American companies believe that there are opportunities there.”

Perry estimated that there are only about three to five American companies actively pursuing deals in power generation or transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. By comparison, dozens of Chinese companies have already invested in Africa’s power sector — backed by the purse strings of Beijing’s massive export finance regime.

Despite Ex-Im’s arguably tepid progress toward its $5 billion financing target, it’s worth noting that the Obama administration reports it has reached more than 25 percent of the initial 10,000-megawatt power generation goal for Power Africa. But USAID clarified that Power Africa achieved this milestone in large part because of deals that had been in the works for several years.

Development without a development mandate?

Although Ex-Im now plays a key role in Obama’s marquee, second-term development initiative, the bank is still, at its core, an export credit agency with a mission to sustain U.S. businesses and jobs. Ex-Im is the only major U.S. government agency participating in Power Africa that is not bound by a development mandate.

The bank and its supporters, however, make the case that if Ex-Im can help U.S exporters get their foot in the door in sub-Saharan Africa’s power sector and, in the process, advance Power Africa’s lofty goal of doubling access to energy in the region, then that’s a win-win for everyone.

“We’re concerned with U.S. jobs but we’re just as proud of the developmental benefits that happen when a power plant gets built in an African country,” Todd said.

Todd did emphasize that Ex-Im is restricted to an export finance role when supporting power projects in sub-Saharan Africa. If a power project needs turbines or solar panels, then Ex-Im can help. But if that project needs capital instead, for instance, then that is largely the purview of OPIC — one reason why CGD’s Leo believes Power Africa’s success hinges far more on OPIC than Ex-Im.

“We can directly go to transaction advisers on the ground or bounce it off different agencies to see if they’ve heard of this transaction — it might be a better fit for OPIC or the development credit authority in USAID,” Todd elaborated.

Some advocates in Washington, on the other hand, have a more skeptical view of Ex-Im’s development role. Doug Norlen, economic policy manager for Friends of the Earth, argued that Ex-Im’s commercial mandate means the bank has little incentive to address the potential social and environmental harm of its transactions.

“Ex-Im Bank doesn’t have a development mandate [and does] projects that result in negative development impact,” Norlen asserted, citing a natural gas pipeline project in Papua New Guinea.

“We’re concerned with U.S. jobs but we’re just as proud of the developmental benefits that happen when a power plant gets built in an African country.”

— Ben Todd, senior business development officer for Africa at the U.S. Export-Import BankEx-Im stressed that despite not having a development mandate, it conducts social and environmental impact assessments of proposed transactions; these are considered to be among the toughest in the export credit industry.

Prompted by Obama’s climate action plan, Ex-Im also unveiled a new carbon policy last year, which further restricted the bank’s financing for high-emission projects, including coal-fired power plants. The bank has not financed any new coal-fired power plants in sub-Saharan Africa since 2011.

Further, since 2008, Ex-Im has been directed by Congress to set aside 10 percent of its total financing authority to renewable energy exports; the bank, however, has consistently fallen short of that target.

“It’s not [just] Ex-Im, there’s an increasing awareness among public finance institutions that public financing for coal and other fossil fuel projects is having a negative development impact,” acknowledged Norlen, who also pressed the bank to end its financing for fossil fuel projects altogether.

Where Ex-Im is still clearly behind in the development curve is in its lack of monitoring and evaluation tools, which systematically track the broader development impact of its transactions. That is not too surprising given the bank’s strictly commercial mandate.

“Ex-Im Bank does have a lot of tracking mechanisms but they deal with numbers of jobs created, number of transactions supported and dollar volumes. On a development basis, they don’t have the same form of mechanisms,” said John Schuster, a principal at the consulting firm 32 Advisors who served as vice president at Ex-Im until May of this year.

By comparison, OPIC publishes an annual development impact report, which tracks the number of jobs created both in the United States and in host countries.

Ex-Im’s Todd suggested that the bank is looking to USAID to lead the monitoring and evaluation of its Power Africa transactions on a development basis. According to Schuster, USAID has been considering the secondment of personnel to Ex-Im.

The bigger if: long-term reauthorization

Looking ahead, supporters of Ex-Im are cautiously optimistic that lawmakers will extend the bank’s charter before June of next year, when the current reauthorization expires.

“If there is a continuing campaign to make the case, I think it can be done,” said the Corporate Council on Africa’s Perry.

The bigger concern, however, is whether Congress will again be reluctant to grant Ex-Im a long-term reauthorization — a scenario that would become more likely if Republicans capture the Senate in November’s midterm elections. In 2012, lawmakers reauthorized the bank for a period of two years and eight months.

Already, the divisive reauthorization debate these past few months seemed to have put a damper on confidence within the bank.

“The biggest problem, with respect to the opposition to the bank, is the effect that this has on the morale and the operation of the bank. It is so difficult for everyone I know at the bank to operate — to do the work that they do,” Schuster said of his former colleagues at Ex-Im.

This current of unease doesn’t stop at Ex-Im’s door. There’s little doubt that many American companies will think twice before approaching Ex-Im if reauthorization turns into a constant struggle for the bank. Ex-Im’s $5 billion financing target for Power Africa would then become all that much harder to achieve.

“We need Congress to pass a full five-year reauthorization to support U.S. exporters as soon as possible,” urged Kevin Kolevar, vice president for government affairs and public policy at Dow Chemical, which supplies solar-related products to South Africa with Ex-Im financing.

“It is not the type of certainty in finance that exporters, buyers, borrowers or anyone wants or needs,” added Schuster.

Check out more insights and analysis provided to hundreds of Executive Members worldwide, and subscribe to the Development Insider to receive the latest news, trends and policies that influence your organization.