It started with a challenge.

In the middle of a conference gathering hundreds of top managers for GlaxoSmithKline, Justin Forsyth, chief executive of Save the Children UK, called upon the crowd to think differently about the way two organizations can partner.

Forsyth pushed GSK to look beyond a traditional monetary “partnership” of GSK just giving money to the organization.

The philosophy Save the Children had adopted was one which director for program policy and quality Mavis Owusu-Gyamfi sums up bluntly as: “We really like your money, thank you very much. But most importantly we’re interested in your skills, expertise and medical platform.”

That speech was the beginning of an 18 month-process through which GSK and Save the Children got to know one another and hammered out the details of a partnership unique for its depth and scope — and a relationship that could serve as a model for other companies and NGOs looking to engage more completely to tackle critical development issues.

Ramil Burden, vice president of Africa and developing countries for GSK, described the partnership as “like a joint venture” that uses the strength of each partner and looks to create long-term sustainability.

There has been a lot of learning and translating on both sides, but it’s the model of engaging around the core expertise of both organizations that can be replicated as companies are increasingly looking at ways to connect their work on development issues to their business.

Now, as the partnership begins its second year, both GSK and Save the Children are looking at progress, what they’ve learned and how to move forward to reach their ambitious goal of saving one million children’s lives.

Multiple points of engagement

The partnership has five key components: programming, research and development, joint-advocacy, employee engagement and cause-related marketing.

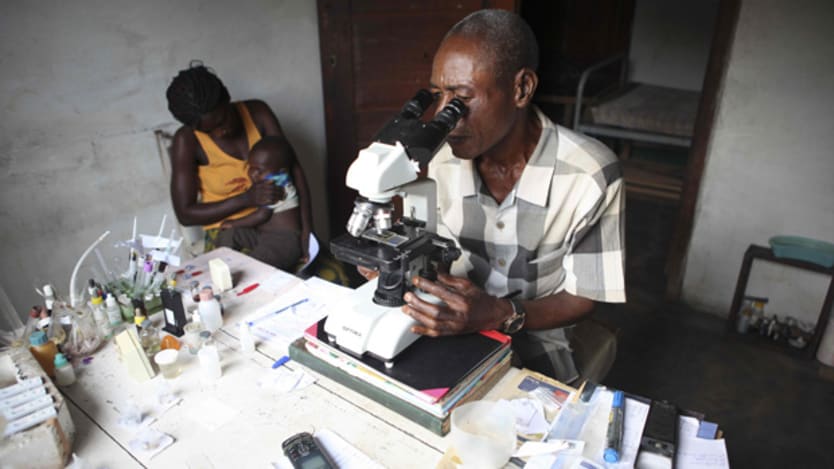

Save the Children UK leads the work on the programming piece but contrary to the past, when GSK has just provided monetary support, GSK staff are now helping to jointly design and implement projects. The first project, launched last summer, seeks to address maternal and under five child health in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In the DRC, Save the Children is taking an integrated approach to help families access essential health services through steps such as training health workers; renovating health care facilities; and improving the medicine supply chain, said Owusu-Gyamfi. A catch-up vaccination program, which is part of the project, has reached more than 2,000 children.

This conflict-ridden country was not GSK’s first choice location for the program, but Save the Children convinced the company to commit to working in a country they wouldn’t normally work in for the first program and agreed to launch the second in Kenya, a more appealing market for GSK.

“If we are serious about really contributing to saving one million lives we have to go not after low-hanging fruit but look at places that need big structural changes,” Owusu-Gyamfi said, adding that if through the program they can understand how to create change in a place like the DRC, it can provide lessons and guide to countries in a similar situation.

The Kenya project recently launched and seeks to to address newborn and maternal health, a gap in a health system that works in some capacities.

Save the Children drives the programs but GSK is responsible for the innovation, as well as the research and development component of the partnership. GSK is more thoroughly examining how products can be adapted for use in poor communities and what new products have the most potential. Through the partnership, Save the Children is now part of that conversation through its seat on GSK’s research and development committee. That role allows Save to provide technical expertise on what works and what is needed in poor communities and influence decisions.

The employee engagement component of the partnership is also multi-layered. Through campaigns in every major global office, GSK employees have raised about 700,000 pounds for Save the Children, which GSK will match. Employees have also been asked to contribute ideas for research or projects that could be tackled through the partnership, with the top ones being being presented to senior leadership for consideration.

Employee engagement goes beyond the fundraising campaigns and includes collaboration with the GSK Pulse volunteer program through which supply chain specialists, doctors and others work with Save the Children U.K. to improve and execute programs that are part of the partnership.

Both GSK and Save the Children see value in coming together with a unified voice to advocate for specific issues with governments and other development actors.

Bumps along the road

Despite the positive outcomes of the partnership, it hasn’t always been an easy process.

While that hasn’t necessarily been a surprise for Owusu-Gyamfi, it has at times felt like a step forward translated to a few steps forward and required more patience and time than she might have preferred.

“I’m very pragmatic,” she said. “Great programs do not happen overnight...they are a series of microsurgeries perfectly coming together.”

The Save the Children country manager in the DRC left as the program was getting off the ground and the program felt the challenges of keeping key implementers with the necessary skill sets in place, Burden said.

“The DRC is an incredibly difficult place to work...these things are well known but until you start working on them you don’t grasp the full scale” he said.

Owusu-Gyamfi described it as a sort of culture shock for GSK the first time they went to visit field staff in the DRC. Even though GSK knew and had heard about the context that the organization was working in, the employees hadn’t seen the living conditions and trade-offs staff had to make.

Internally Owusu-Gyamfi also struggled to get the whole organization to support the partnership. While she had done work in getting buy-in before the launch of the partnership, she said if she could do it over she would spend more time with Save the Children to show them the value of the partnership, quell concerns and define their roles.

“If you want to be transformational, it’s not that straightforward,” she said, adding that a lot of monitoring was necessary to ensure that staff understood their roles and how things would operate differently through the partnership.

Another early trial has been trying to determine how to best measure the impacts of a complex, multi-layered partnership. To address the monitoring and evaluation question, the partnership plans to hire an independent, third-party evaluator to design a measurement framework and track progress.

The process of working together to address all of the issues has strengthened the relationship between the two organizations, Burden said.

Early successes

The partnership, with its various components, is only a year and a half old, but already it seems to be delivering a few key achievements.

GSK created a powder form of amoxicillin, which can help fight pneumonia in children under 5 that has received market authorization in the DRC. Building on an existing program, the partnership is also training more health workers.

The partnership has also identified and sped the development of a chlorhexidine, an antiseptic gel that can be used to clean umbilical cord stumps to prevent infections.

Chlorhexidine, a reformulation of an antiseptic in a GSK mouthwash, could help tackle a major cause of newborn deaths in developing countries. Studies from South Asia have shown that reducing those infections could prevent up to one in six newborn deaths in low resource settings, according to GSK. The development and approval process will take time but GSK aims to register chlorhexidine in 2015.

The product, which may have a commercial market but is unlikely to be profitable, was not a priority for GSK without the partnership.

Save the Children has also taken on projects or new approaches through the partnership that would not have been possible without the deeper, more intense and longer-term commitment.

“If GSK had given us a check we would have done some components, but the partnership enables us to be bolder,” Owusu-Gyamfi said, explaining that they can look at supply chains and government procurement systems because they now have the necessary skills on the team.

As they look ahead, Burden said that GSK will continue to have a strong commitment but is always looking to build sustainability into the programs, so the are not forever dependent on GSK funding. Both organizations would welcome other companies or organizations to join this partnership and is open to working with both those inside and outside the pharmaceutical sector.

GSK is unlikely to pursue another partnership like this at this time, but Save the Children is in active discussions to use this model in different settings with different companies or organizations. An announcement on a partnership tackling diarrhea and sanitation is upcoming and another related to education is also in the works.

“We’ve charted a path to use in strategic conversations with other corporates,” Owusu-Gyamfi said.

Do you have an example for a cross-sector partnership that promotes sustainable development without depending on continuous funding from the private sector? Let us know by leaving a comment below!

Join Devex, the largest online community for international development, to network with peers, discover talent and forge new partnerships — it’s free. Then sign up for the Devex Impact newsletter to receive cutting-edge news and analysis every month on the intersection of business and development.