Malaria vaccines have made headlines in recent years. But beating malaria requires a combination of tools.

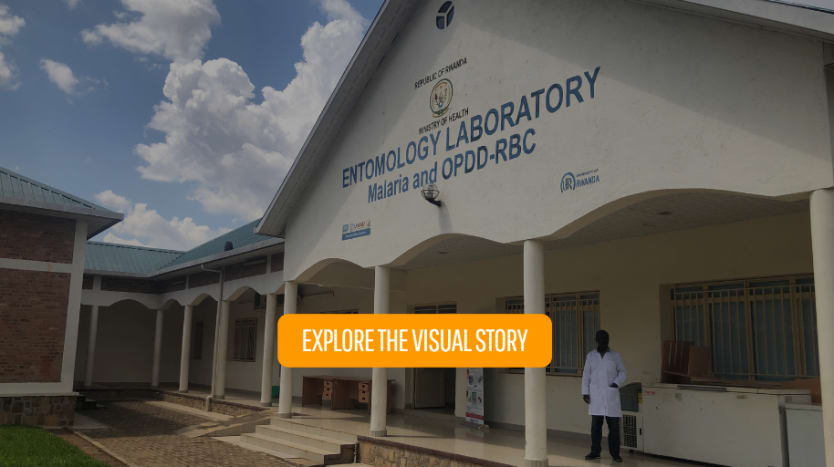

In Rwanda, scientists in white lab coats toil away daily at the country’s entomology laboratory, studying Anopheles mosquitoes that spread malaria. They keep thousands of samples in a huge cabinet and test different parts of the mosquito: the legs and wings for DNA, the abdomen for blood to help scientists identify what they fed on, and the head and thorax to identify the malaria parasite.

The task feels mundane, but it serves a critical purpose in the country’s malaria control efforts. It helps them determine where malaria is in transmission, what vector and parasite is circulating, and whether the vector control interventions the country employs, such as the use of insecticide-treated bed nets and indoor residual spraying, are still working.

The role of the lab is even more critical as the country faces the twin threats of drug resistance and climate change.

Dunia Munyakanage, vector control supervisor at the lab, perfectly sums up their work in a few words: “If you don't have a lab, then you are like a blind person. You can only guess.”

Keep reading: Join Devex on the ground in Rwanda as we explore the country’s efforts to control the spread of the ancient disease of malaria in this visual story.

Editor's note: Novartis facilitated Devex's travel and logistics for this reporting. Devex retains full editorial independence and control of the content.