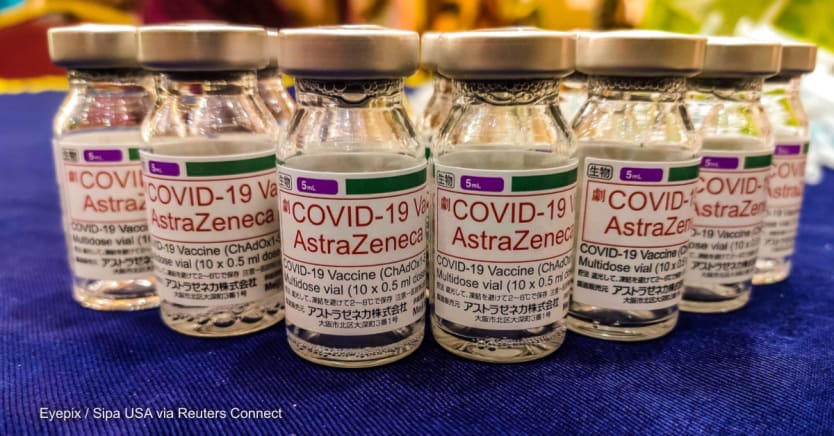

Is Botswana's private COVID-19 vaccine offer too good to be true?

This week, former Botswana President Seretse Khama Ian Khama announced that his foundation has secured two million doses each of the AstraZeneca and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines for the government of Botswana.

Sign up for Devex CheckUp

The must-read weekly newsletter for exclusive global health news and insider insights.

In a statement issued Aug. 9, the SKI Khama Foundation said the vaccines were “available to the country immediately upon submission of a purchase order and an end-user-certificate, both of which must come from the government of the receiving country as per established procedures and protocols for the acquisition of COVID-19 vaccines.”

The statement explained that the vaccines were secured through the KKM Global Group LLC — a multidisciplinary health services group — from manufacturers based in the United States, but that the offer was only valid for five business days.

Though some citizens hoped that this announcement would result in some much-needed reprieve for Botswana, which has had limited access to vaccines, vaccine manufacturers warned that they do not supply vaccines to private distributors and that such vaccines are likely counterfeits.

A Pfizer spokesperson said the company “has no relationship or dealings with KKM,” and that all their current COVID-19 vaccine supply agreements are with governments or supranational organizations such as COVAX — who “are in the best position to fairly and equitably distribute these vaccines across their populations.”

“Currently, there is no authorized private distributor of our vaccine worldwide. The quality and efficacy of any vaccine moving through any non-authorized channels cannot be assured and should be viewed as suspect potentially putting lives at risk,” they said in an email.

Likewise, a spokesperson from AstraZeneca said the manufacturer is focused on delivering on the substantial global commitments they have already made to governments and international health organizations.

“We use our association, our relations, and our diplomacy with that network to be able to access that which up to now had proven to be a challenge for the government of Botswana to achieve.”

— Mogomotsi Kaboeamodimo, chief executive officer, SKI Khama Foundation“There is currently no private sector supply, sale or distribution of the vaccine,” they wrote in an email. “If someone offers private vaccines, it is likely counterfeit, so should be refused and reported to local health authorities.”

But David Knott, president at KKM Global, insisted that the company is “a registered distributor of several COVID vaccines” that is focused on providing the people of Africa and Botswana with COVID-19 vaccines.

“KKM works directly with license manufacturers and foundations, also developing several Pan African licensed ‘End to End’ and ‘Fill and Finish’ manufacturing facilities to provide vaccines ‘In Africa for Africa,’” he told Devex.

He added that “original drug manufacturers” do not dictate the delivery destination of all the products being produced by fill and finish and end-to-end contract manufacturers, and that KKM “will not allow politics to get in the way of saving people’s lives.”

Though Mogomotsi Kaboeamodimo, chief executive officer at the SKI Khama Foundation said the foundation had vetted KKM Global for over two months and established that the company is “a duly licensed supplier” of medical products including vaccines, he also said the company’s license “is not customized to COVID-19” and the foundation did not look into KKM’s relationships with COVID-19 manufacturers.

The offer comes at a time where relations between Khama and his successor, President Mokgweetsi Masisi’s government are strained. Though Khama hand-picked Masisi, the two publicly fell out soon after Masisi took office in 2018. This resulted in Khama leaving the Botswana Democratic Party — founded by his father and has been in power since independence in 1966 — to form an opposition party, the Botswana Patriotic Front.

Kaboeamodimo said the foundation had secured the vaccines through its network of international and local partners and that he hopes these political differences will not play a role in the government's decision regarding the offer.

"We use our association, our relations, and our diplomacy with that network to be able to access that which up to now had proven to be a challenge for the government of Botswana to achieve," he said. “I obviously hope that sense and reasonableness will prevail today so that we all prioritize saving the lives of Batswana and put political differences or whatever differences aside.”

African nations gear up for an influx of COVID-19 vaccines

African nations are expected to receive millions of doses of COVID-19 vaccines in the coming weeks. One of WHO's key concerns is how countries will manage to roll out multiple types of vaccines within one national vaccination plan.

Though the country is expected to receive shipments of over 200,000 purchased and donated doses of vaccine this week, including 108,000 doses of the Johnson & Johnson single-dose vaccine, it has only fully vaccinated just over 5% of the population — a far cry from the African target of vaccinating 60% of populations to achieve herd immunity. The vaccines offered by KKM would theoretically cover over 80% of the country’s population of an estimated 2.37 million people.

The offer also comes at a time when the country is battling a deadly third wave. This week, the country experienced 926 cases per million people per day — the highest on the continent. Local hospitals have been overwhelmed by the rising number of cases and experienced oxygen shortages.

Though the government has not yet responded to the offer or to requests for comment, Assistant Minister of Health and Wellness Sethomo Lelatisitswe questioned the pricing of the vaccines during an interview with a local radio station, stating that the proposed purchase price of $22 per dose for the Pfizer vaccines was exorbitant. According to the People’s Vaccine Alliance, Pfizer is charging the African Union their lowest reported price of $6.75 per dose.

But Kaboeamodimo countered that one cannot balance cost against saving lives.

“Is there a cost to life,” he asked. “If you value human life and believe the country has a crisis and you are keen to save lives … you prioritize; you shift resources to fight the pandemic.”

Search for articles

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5