MANILA — World Health Organization member states agree on the importance of access to medicines to achieve universal health coverage, but at the recently concluded 142nd session of WHO’s executive board, it was clear they have different and strong opinions on how to make that happen.

The issue of timely access to quality, affordable health products — medicines, vaccines, diagnostic tools — has become a huge topic in global health in recent years, not only among developing countries but even among high income ones. The high cost of products such as cancer medicines, for example, have prompted calls from different quarters for transparency of research and development costs — particularly by pharmaceutical companies. One of the most expensive cancer drugs out in the market today to treat leukemia among children and young adults costs nearly $500,000 per patient.

But the issue has been of particular significance to developing nations, whose populations are not only struggling to keep up with costs of expensive drugs for noncommunicable diseases, but also for lifesaving ones such as pneumococcal vaccine, drugs for tuberculosis, and hepatitis C.

13 things to know about WHO's Geneva deliberations

While the world’s elite gathered atop the snowy mountains of Davos, health ministers and other stakeholders hammered out the details of a number of global health priorities in Geneva. Here’s what to know about the World Health Organization's weeklong 142nd executive board meeting.

As much as 90 percent of populations in developing countries pay out of pocket for medicines, according to WHO’s latest report presented to member states. This puts huge numbers of people at risk of financial hardship, posing significant challenge to attaining universal health coverage, an overarching goal in the Sustainable Development Goals and the central theme in Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus’ vision and mission for WHO’s work in the next five years.

The topic has been discussed for years at the executive board and at the World Health Assembly. To illustrate, WHO’s latest report is based on a review of 50 World Health Assembly resolutions directly or indirectly related to the issue of medicine access, 45 regional technical consultations and 67 technical documents, said Dr. Mariângela Batista Galvão Simão, WHO’s new assistant director-general for drug access, vaccines, and pharmaceuticals. The report covers different priorities of action for member states, depending on the level of complexity and the amount of resources needed to implement them. It also looks into areas where WHO needs to step up knowledge and action on its technical support function, from inducing savings through innovative procurement approaches to helping countries navigate the flexibilities provided in the trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights, or TRIPS, an international, legally binding agreement between countries and the World Trade Organization.

“This is the third year in a row that this item is both in the EB and WHA agendas, and this reflects how important it is and also the complexity of access to safe, quality-assured, affordable medicines, vaccines, and pharmaceutical products, including diagnostics and medical devices and other health technologies” said Simão, who underlined the need to streamline and prioritize action on the issue.

As if conditioning member states, the assistant director-general said: “The decisions we make on this board have consequences in the real world, and they affect how this outcome of people having access to different technologies can actually take place.”

A step forward for medicine access

A number of member states echoed the assistant director-general’s message of how important, and difficult, the issue of access to medical products are in their respective countries. Speaking on behalf of Eastern Mediterranean countries, Jordan’s representative said access to quality assured and affordable medicine is a problem faced by many of the countries in their region, including those with middle-income status, and that they require WHO’s support on supply chain management and procurement “both in normal and emergency situations.”

Netherlands, a high-income country, shared the same sentiment.

“We urgently need comprehensive guidance and assistance from WHO, taking into account all aspects, also the difficult ones, such as fair pricing, quality of drugs, appropriate use and of course [intellectual property],” the representative said, adding that they, too, are considering the application of compulsory licensing — allowing the manufacture of products under patent without seeking consent of patent holders — but like many countries face difficulties, political and legal.

The Brazilian representative, meanwhile, underscored just how hugely relevant access and affordability is across all the issues being discussed by the executive board.

See more related topics:

► WHO's draft program of work: Some answers, then questions

► Opinion: 5 agenda items to watch at WHO's annual board meeting

► Tedros announces WHO senior leadership team

► For his first 100 days, WHO's new DG Tedros gets a nod of approval. But can he sustain it?

► With new WHO director appointments, women outnumber men in senior leadership

“It is useless, for example, for a country to offer broad health coverage if individuals who seek medical facilities do not receive medicines or cannot purchase them. It is pointless to deploy a costly response team or the health reserve forces so central to [the director-general’s] vision of a transformed WHO if they do not have the means to quell an emergency, or to immunize and treat displaced populations,” the Brazilian representative said.

Both Brazil and the Netherlands ended their speeches asking the director-general to take a stand and put public health needs at the center of the discussions on access to “keep people from dying before their time.”

Some member states, such as Japan and the United States, raised questions on the report and the roadmap outlining WHO’s work on access to medicines and vaccines for the period 2019-2023, but in the end agreed to adopt the proposed decision put forward by Brazil and other countries.

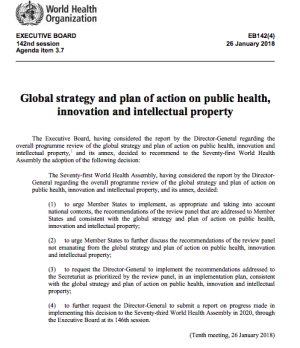

But it was a different ball game altogether when member states started talking about the global strategy and plan of action on public health, innovation and intellectual property, or GSPoA, which has been adopted by the World Health Assembly a decade ago but have not seen full implementation to date.

A long road to consensus

A number of member states were proposing a draft resolution that allows WHO and its member states to take forward the recommendations of the expert panel WHO convened to do a program review of the GSPoA. The new set of recommendations mostly came from the GSPoA, but the difference is that it contains a more focused set of actions for WHO and member states. The panel reduced the recommendations from 108 to 33, but that included a few additions that sparked hours of debate and negotiations between countries. The additions were aimed at promoting transparency and understanding of research and development costs, and asking member states to dedicate at least 0.01 percent of their gross domestic product to “basic and applied research relevant to the health needs of developing countries.”

The representative from Japan noted that R&D promotion is very important to progress on UHC. But he argued that it can only be done by providing incentives to companies in the development of news drugs, and that means providing “adequate protection” of intellectual property. He also raised concerns on the added recommendations, and asked the board more time to understand their full implications.

The United States representative meanwhile was more direct in saying his delegation cannot support the draft decision point proposed, and requested the creation of a drafting group to make revisions. He argued that some of the recommendations weren’t based on consensus among member states. A recommendation on transparency that seeks to calculate and get companies to disclose their R&D costs “are impractical and unlikely to be effective,” the representative said. Instead, he argued, such an approach could only result in companies abandoning research that could be most beneficial to communities and “humanity as a whole.”

“In addition, we do not support calls for WHO advocacy and areas outside its mandated expertise, including intellectual property rights for which potential long-term consequences to global innovation would be devastating,” the representative added. “The United States maintains it’s inappropriate for WHO to intervene on matters in the domain of the World Trade Organization, particularly with respect to interpreting member states’ legally binding TRIPS obligations.”

WHO’s future action, the U.S. representative said, should focus on areas where there are consensus, and member states should focus on policies that “genuinely promote access to medicines while continuing to allow the global innovation system to flourish.”

Since the United States is not a member of the board, Japan agreed to file their request for a revision of the proposed draft decision point before the executive board.

But the U.S. response triggered a series of reactions among member states. It was apparent that similar arguments have been made in the past, and some member states are wary that the discussions would again lead nowhere.

“GSPoA is not against protection of intellectual property. On the contrary,” said the Brazilian representative. “We have gone through the motions for the last 10 years, like Congo put very well, we have discussed, we have negotiated, we have agreed within this EB, we have sent our agreement to the WHA, we have agreed at the WHA, then what we had agreed is not implementable. Then we created a working group. Not implementable. Then we hired a consultant. Not implementable. Then we put together a group of experts. Not implementable. Now, not implementable, 10 years later.”

She went on to say that protection is not at risk, and that the recommendations in the report are not “threatening anyone, any industry.” She made it clear that the board is not meant to reopen the TRIPS agreement, but just to ensure all of its aspects are implemented, not just the intellectual property protection it provides, but also its flexibilities, from which member states struggling in meeting their populations’ treatment needs can benefit from.

“This dilatory tactics are not acceptable. They are not adequate. They are not in line with the mission of WHO,” the representative said, stressing that Brazil won’t accept any proposals that would delay the recommendations’ implementations. If there are a few recommendations that member states such as the U.S. and Japan are wary of, the representative suggested creating a separate process for those alone, but approve the rest that raised no issues.

Thailand, Netherlands, Libya, Algeria, and others moved in support of Brazil’s proposal, while countries such as France and Sweden sided with the proposal by Canada to create a drafting group that would revisit the decision point as a means to agree on a compromise, though with a caveat that only “minor modifications” will be made in the current proposal. After a few back and forths, Brazil agreed to Canada’s proposal, but stressed making only “minor adjustments” to the decision point they made.

“We are not committing ourselves to a delay in approval of this decision,” the Brazilian representative stressed, and adding that the group to work on the draft be composed of only executive board members.

It wasn’t clear what board members had decided on by the end of the session, but Devex learned later that an informal group met over lunch time outside the formal executive board sessions to renegotiate the text, and it included anyone interested in the decision, board member or not. The deliberation extended beyond lunch, leaving the Republic of the Congo’s representative, who earlier expressed being witness to discussions on the issue at WHA for eight years, wary of the direction of the negotiations.

“I’m not by nature a pessimist, but I think the basis of the problem here is the consensus of the document before the draft decision. There are points where there are divergences. If that’s the case, we can hold X meetings, [but] we’ll never reach an agreement. And I’m afraid this will start to drift in the wrong direction.”

The representative from Malta however countered, saying the board must not give up, noting there’s a “lot of goodwill during the negotiations.”

By late evening though, it was clear the drafting group had not reached a consensus yet. But the following morning, after the board discussed a few agenda items, Colombia, who co-chaired the drafting group with Malta, announced they’ve reached consensus.

Mixed reactions

Formally, at the session, members states appeared accepting of the agreed draft text. But a member of delegation involved in the process told Devex afterward that the compromised text was reached so as not to risk losing the whole report altogether. Some of the developed countries, said the source, who requested to remain anonymous as the negotiations were meant to be private, were not showing signs of flexibility, and the longer the negotiations went, the more issues arose. Some of the developed countries involved, who initially were just focusing on two recommendations, came up with several other issues, the source said.

“It was very risky, and so we decided to move forward,” the source said. “So to save it, we had to separate the recommendations.”

The agreed text reads:

Asked what the agreed text means in terms of implementation, the source said the text allows member states to implement every recommendation, except for the following, which the agreed decision points specifies requires further discussion:

1. Member States to support the WHO Secretariat in promoting transparency in, and understanding of, the costs of research and development. (Indicator: Reports on the the costs of research and development for health products prepared in 2019 and 2021.)

2. Member States to identify essential medicines that are at risk of being in short supply and mechanisms to avoid shortages, and disseminate related information accordingly. (Indicator: Lists of medicines at risk of being in short supply and information on mechanisms for preventing shortages made available and disseminated by 2020.)

3. Member States to commit to dedicating at least 0.01 percent of their gross domestic product to basic and applied research relevant to the health needs of developing countries. (Indicator: Percentage of gross domestic product dedicated to basic and applied research as reported by G-Finder by 2021.)

“But the thing is, the report itself recognizes that we’re different recipients of the recommendations. For those related to member states, we could not get stronger language to call for the implementation without the caveat of national contexts,” the source said. “But an important aspect is that the WHO Secretariat will be able to implement the decision.”

As with any negotiations, those who were advocating for a full adoption of the recommendations were not entirely happy. For example, the language wasn’t strong enough to persuade member states to implement the recommendations outside of their “national contexts.” But they had a few wins, including getting the WHO Secretariat to implement the decision. In addition, a roadmap for WHO’s work on access to medicines for 2019-2023 was agreed in a related decision point.

This was seconded by an NGO member who was in Geneva following the discussions closely.

“The good thing is at least we can now hope for some progress at WHO level in the priority recommendations, which is about time after 10 years delay,” an expert on the topic who was following the discussions told Devex, requesting not to be named to protect their affiliations.

James Love, director of NGO Knowledge Ecology International, said they were surprised with the U.S. opposition to measures that would make R&D costs publicly available.

“When negotiating drug prices, or designing and evaluating incentives mechanisms and new business models, having good and granular data on actual R&D costs is important. Promoting ignorance to protect excessive prices and bad business models is inexcusable,” he said in a statement.

But they, too, were encouraged by parts of the decision that gives WHO broad mandate to act. His colleague, Thiru Balasubramaniam, KEI’s representative in Geneva, said: “We are heartened that the decision encourages countries to implement schemes which ‘partially or wholly delink product prices from R&D costs.’”

What happens here on out will depend on political will.

The representative from Thailand, during the session, called on the director-general and member states to “walk the talk.” Since 2007, the representative said WHO has had 50 resolutions and plans on the topic.

“It’s proof that resolutions and plans, without effective actions, waste our time,” the representative said.

Read more Devex coverage of the World Health Organization.