Opinion: 5 ways cash transfers are improving humanitarian response

The 2015 high-level panel on humanitarian cash transfers challenged humanitarians to ask “why not cash?” and “if not now, when?”

See more related topics:

► DFID's approach to cash transfers: Time to 'learn by doing?'

► Opinion: E-transfers don't naturally promote financial inclusion — but they can

Over recent years, the scale-up of cash assistance in crisis response has changed the way humanitarians operate. Cash supports local markets and economic regeneration, empowers recipients, and allows them to prioritize their needs. Up to 80 percent of people in crises prefer cash to in-kind aid. Cash can be faster and cheaper to deliver: Studies show cash is 25 to 30 percent more efficient than in-kind aid, while up to 70 per cent of in-kind aid ends up being re-sold. Cash assistance can also help us link to longer-term recovery and to government-led efforts to support affected citizens.

Perhaps most importantly, cash also forces humanitarians to raise standards across the board. It shines a light on many of the flaws inherent in the humanitarian system, and pushes aid groups to make changes so that they are fit for purpose. Many of the changes catalysed by cash responses, including thinking through the right response tools to meet needs; linking up across better sectors; and aligning response more closely to needs assessments, simply equate to better planning and programming.

Here, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs outlines five ways that the increasing use of cash is improving humanitarian response.

1. Cash forces us to use the right tools in the right places at the right time

As humanitarian needs reach unprecedented levels, and the gap between need and response grows, aid agencies must use the limited resources at their disposal as efficiently and effectively as possible. This includes rethinking response by using new tools and channels. But all too often, aid groups roll out the same prepackaged solutions.

In Nepal, following the 2015 earthquake, Shobha Shrestha, a geography professor at the University of Kathmandu, turned up at the OCHA office one morning to offer her time and expertise to help the relief effort. She produced a map overlaying the severity of food needs across the country with road access, and the presence of functioning financial service providers. The map made it clear where airdrops should be focused — high need, no road access, no financial service providers; where road deliveries were most appropriate — high need, road access, no financial service providers; and where cash transfers could be used — high need, road access, functioning financial service providers. By asking “where can we use cash?,” humanitarians force a discussion about the most effective tools across the response, leading to a more efficient allocation of resources.

2. Cash helps humanitarians reach the places other tools cannot

In 2016 and 2017, drought pushed 3.5 million people in Somalia into severe food insecurity. Humanitarian actors battled to avoid a repeat of 2011, when restricted access to the worst-affected parts of the country contributed to an inadequate response to famine conditions, leading to the deaths of 260,000 people. This time too, widespread insecurity meant that humanitarian convoys could not reach many of the worst-affected areas. However, a highly resilient market system has continued to operate in Somalia through 25 years of conflict, meaning almost every part of the country continued to be accessible to private traders. In 2017, aid agencies made cash transfers to 500,000 households, benefiting up to 3 million people, enabling recipients to buy lifesaving food and other goods on local markets, which played a critical role in helping to avert a famine.

3. Cash supports local markets

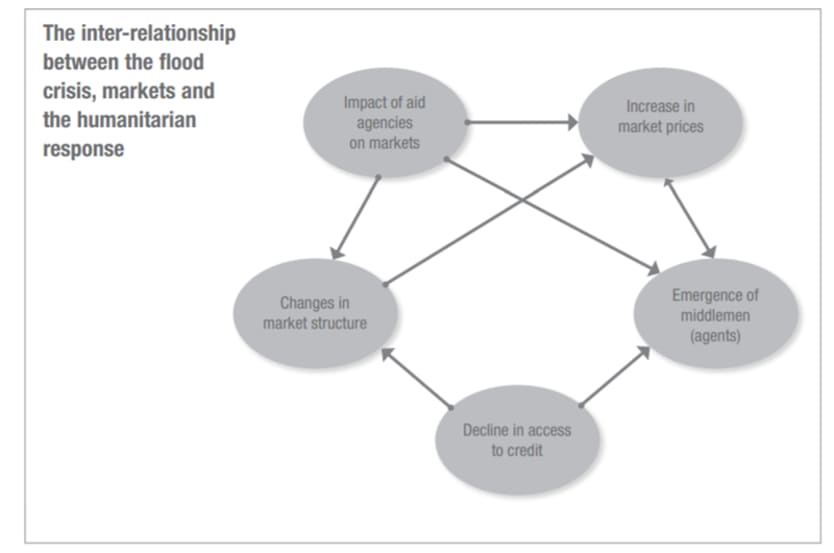

Increasing the use of cash means humanitarians must take market assessments more seriously, understanding the fragile local ecosystems through which they often channel our humanitarian aid. When humanitarians don’t do these assessments, they can cause harm. For instance, following the floods in 2010 in Sindh, Pakistan, the distribution of food aid and the large-scale purchase of bamboo for shelter reconstruction had negative impacts on small- and medium-sized traders, slowing the pace of recovery for those communities. Market assessments should be part of every humanitarian response, everywhere. And wherever aid groups can respond through local markets, they should.

4. Cash helps us work better with governments and the private sector

Humanitarians know they need to work better in support of governments, but knowing how to do this is often a challenge. From Ethiopia to Yemen to Turkey and beyond, humanitarians are increasingly working with governments to deliver cash transfers through or alongside their existing social protection systems. Cash response also allows them to forge unconventional partnerships that deliver better results. Private sector partners often have the best channels, access, knowledge, and contacts to reach people with assistance, as well as the strongest data on where people are going and what they need. Learning to work better with private sector colleagues is essential.

5. Cash forces us to think like economists and place humanitarian response in the bigger picture

If we’re honest, as humanitarians, economics is rarely our strong suit, yet micro- and macroeconomic dynamics in crisis-affected countries have a significant impact on needs and response. We need to better understand the impact of inflation, imports, remittance flows, and exchange rates on the humanitarian situation, and, likewise, how humanitarian action impacts these dynamics.

In Yemen, while calculating how much a monthly cash payout should be for crisis-affected people, the Cash Working Group noticed a vast difference between the officially set exchange rate used by humanitarian groups, and the market exchange rate used by others. Humanitarian groups took this to the Yemeni government, which subsequently officially floated the Yemeni currency. As a result, aid agencies could renegotiate the exchange rates available to them, stretching cash payments to more people and saving more than $80 million, or 6 percent of 2017 humanitarian funding for Yemen.

The scale-up of cash assistance is changing the way humanitarians do business in a number of important ways, and further evolutions in our systems and approaches are needed.

Humanitarians face a fundamental choice: Do they fit cash solutions into our existing systems, or do they embrace the cash challenge by changing the way they organize, plan, and deliver humanitarian responses across the board?

Search for articles

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5