Before the COVID-19 pandemic, few people spent much time thinking about global health supply chains. Suddenly, many found themselves worrying about when the next stocks of toilet paper, hand sanitizer, and face masks would arrive in stores. But aisle shelves soon filled up again, and any thoughts of supply chains evaporated from people’s minds as quickly as a squirt of antiseptic spray.

But the global health supply chain hadn’t merely suffered a minor bump. It was an earthquake whose aftershocks would be felt for years to come in low- and middle-income countries, further highlighting their need for more resilient supply chain systems to both recover from this shock and shoulder the next one — whether an epidemic, pandemic, earthquake, hurricane, or blocked shipping lane.

Supply chain disruptions can lead to missed doses of tuberculosis or HIV medication or to the death of a child because a malaria diagnostic test is unavailable. A lack of access to contraceptives leads to unplanned pregnancies and to children — especially girls — missing out on education opportunities if families face resulting economic hardship. The United Nations Population Fund and Avenir Health estimate that the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted family planning services for 12 million women, leading to 1.4 million unintended pregnancies.

There must be greater collaboration between all stakeholders, including suppliers, customers, logistics providers, and others, to build holistic solutions across supply chains.

—The supply chain toolkit

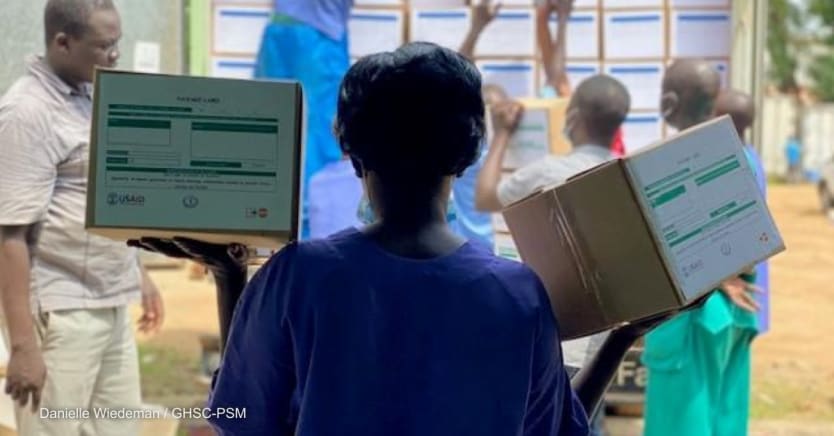

The U.S. Agency for International Development’s Global Health Supply Chain Program-Procurement and Supply Management project, or GHSC-PSM, has been working with country partners for the past five years to strengthen their public health supply chains. The nearly $10 billion project is more than four times as large as the previous largest award in USAID’s history, reflecting the importance the agency places on having robust supply chains for improving global health.

GHSC-PSM helps strengthen supply chains in a variety of ways. These include:

• Data for decision-making. Timely and accurate data is crucial for supply planning and forecasting to ensure that the right quantity of medicines will be available for distribution and dispensing at health facilities.

• Electronic health information systems. Many countries still use paper-based systems for recording data. Electronic information systems make it more likely that supply chain planners will receive accurate and timely data for supply planning and forecasting.

• Warehousing and distribution. Commodities must be stored in a clean and organized manner to prevent spoilage and be distributed efficiently.

• Capable supply chain workforce. Training is a key component for sustainability as governments increasingly manage and outsource supply chain processes.

• “Last-mile" delivery. “Last-mile” dynamic — or flexible — routing solutions can help assure commodities reach even the remotest destinations.

For an idea of how many people depend on supply chains for their medical and family planning needs in just the countries where GHSC-PSM works, the project in recent years has delivered enough artemisinin-based combination therapies to treat about 320.3 million malaria infections and more than 12.5 million patient years of antiretrovirals to treat HIV. It also delivered enough contraceptives, when combined with proper counseling and correct use, to prevent approximately 27 million unintended pregnancies.

Adaptation for resilience

Consequences of supply chain disruption in LMICs

Family planning and reproductive health: Demand for contraceptives can fall when women are unable to access family planning services at health facilities or if they are unable to get their preferred contraceptive method, resulting in unintended pregnancies.

Mothers and newborns: Supply chain disruptions trigger higher mortality rates among women and children, in part because of lockdowns or the unavailability of vaccines and other medications. Or these services could be deprioritized, impacting demand.

HIV: Demand could fall during a pandemic as people decrease their visits to health facilities. Testing targets for the year might not be met. This could lead to overstock of confirmatory tests and possible expirations.

Malaria: The planned mass distribution of long-lasting insecticidal nets and other preventive interventions could be disrupted. As a result, the malaria caseload can increase and therefore demand for malaria drugs can spike, leading to potential stockouts of drugs.

After the pandemic hit, GHSC-PSM created a post-COVID-19 recovery guide for supply chain managers. The Recovery Strategies for Public Health Supply Chains Post-Black Swan Event provide guidance around planning for recovery, weighing information and advice received, and making informed decisions based on a circular feedback loop of assessment and reassessment.

Supply chain recovery does not mean returning to “normal,” as conditions have changed. For example, patients may continue to have new product preferences, shifts in populations can be long-lasting, new supply or distribution channels created during the crisis can continue, and new processes adopted to aid in the emergency could become the new standard operating procedure.

To future-proof supply chains in advance of another pandemic, the global community must invest in technology and innovation that can improve supply chain flexibility to address random and high-impact events. For example, data must be available in real time to make quick decisions, supply chain workforces must be well trained and prepared, and last-mile delivery must have flexible routing solutions.

Additionally, there must be greater collaboration between all stakeholders, including suppliers, customers, logistics providers, and others, to build holistic solutions across supply chains. One thing the COVID-19 pandemic laid bare was just how connected communities around the world are to one another. It’s important to use those links for global, and individual, advantage to prepare for the next crisis.

For more information, listen to the three-part podcast “Unbroken: Forging Supply Chain Resilience” from GHSC-PSM.

Visit the Building Back Health series for more coverage on how we can build back health systems that are more effective, equitable, and preventive. You can join the conversation using the hashtag #BuildingBackBetter.