Years ago, when I worked in a maternal and child health clinic in my native Pakistan, I met a young, newlywed couple. The wife was still a teenager. They came to the clinic looking for family planning so she could finish school, they could get to know each other better, and eventually earn enough to support a family.

It was one of many interactions I had in my years as a physician that cemented what I long knew — that family planning is one of the most powerful tools we have to control our own reproductive health so we can shape the lives we aspire to.

Even in a time of economic uncertainty, family planning remains a good investment. By some estimates, every dollar invested in family planning generates $8.40 in health savings and socioeconomic gains. UNFPA data from 32 low- and middle-income countries showed a strong correlation between women’s empowerment and their access to essential health services like family planning.

Yet, despite family planning being one of the world’s greatest anti-poverty innovations, many women and girls still don’t have access to contraceptives. Today, 218 million women and girls globally want to prevent or delay pregnancy but are not using a modern method of contraception.

In many places, family planning may not be offered at the local health clinic, requiring women to travel far distances to a different health post. The nearest pharmacy may not carry a woman’s preferred method or refuse to provide contraceptives if she’s not married. Cost can also be a barrier — especially for those who are un- or under-insured.

Last month, I was in Thailand meeting with a vibrant community of family planning leaders, government officials, youth advocates, and scientists at the International Conference on Family Planning. Together, they’re reimagining and testing new approaches to break down the barriers that keep family planning out of reach — something that the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation prioritizes in our gender equality work.

And their efforts are working.

More countries are introducing policies incorporating family planning into primary health care systems, where they can reach people closer to home. In 2021, Uganda approved its first-ever national social health insurance scheme, which included family planning counseling and services. Ghana also introduced family planning into its national health insurance program. And India has debuted a national plan to bring health care that includes family planning to more than 500 million people.

Many countries are also increasing their own domestic financing for family planning programs and becoming less reliant on donor dollars, so family planning services are more reliable and sustainable. Last month, Chad, Ethiopia, Madagascar, and Nigeria signed cost-sharing commitments with UNFPA to increase the share of their domestic health budgets spent on contraceptives.

Countries are also adopting innovative approaches to expand access to contraceptives via telehealth, as well as through private pharmacies and drug shops, where more than 1 in 4 women in low- and middle-income countries get their family planning products. In Nigeria, Honey & Banana is an online platform making pregnancy prevention as simple as possible. People can find information on family planning options, chat or call a counselor, book an appointment at their local health clinic, and even purchase contraceptive methods online.

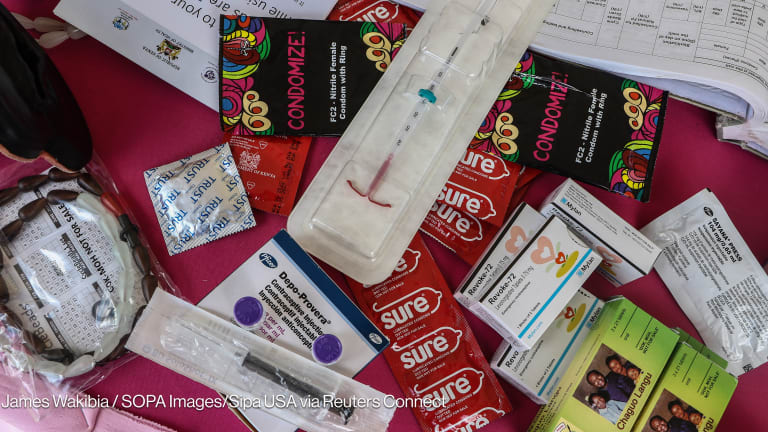

We know that 40% of women in low- and middle-income countries stop using contraception in the first year because they’re dissatisfied with their method. So, I was also excited to see researchers working on new contraceptive options that better meet the needs of women and girls by putting them in control and empowering them to make their own contraceptive decisions on their own time.

The success of these programs and innovations rests on the financial support of donors and countries alike. Yet, despite growing demand for contraception, funding for family planning has essentially flatlined. And as countries rebuild from COVID-19 and face tough choices about how to spend limited funds, family planning funding is at risk.

To meet the family planning needs of women and girls, total funding for family planning must increase. Otherwise, a woman who travels half the day from her rural village to obtain contraception at her nearest clinic may go home empty-handed or be given a method that doesn’t work for her.

At the International Conference on Family Planning, I was reminded of two things time and again: First, our work must be guided by the needs, preferences, choices, and desires of women and girls. Second, family planning is key to unlocking our vision for a fair future. One where everyone has access to good health care, economic opportunity, and importantly, a place at all decision-making tables.

Update, Dec. 6, 2022: This article has been updated to clarify that Chad, Ethiopia, Madagascar, and Nigeria signed the UNFPA cost-sharing commitments last month.