Scaling drone health solutions in Africa

Though Africa has been a global leader in the drone field, projects still fail to secure follow-on funding to scale. Experts say sustainable funding and diverse business models are the solution.

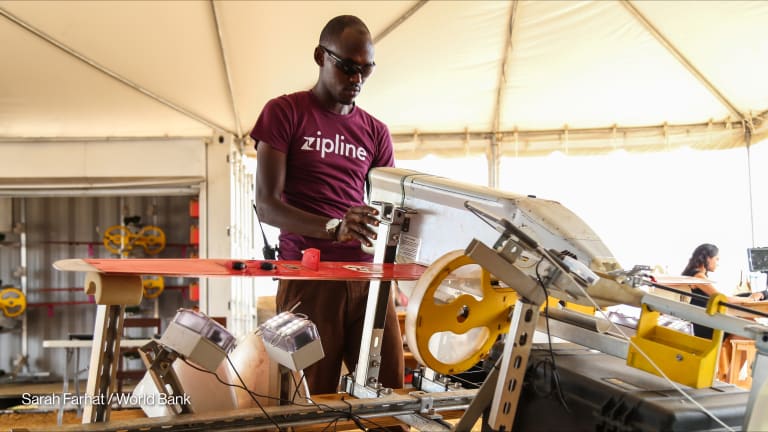

On a quiet afternoon, a lone drone can be seen making its slow descent as it lands at Zipline’s Kayonza distribution center in eastern Rwanda. In one day, the center has made over 100 deliveries, with a fleet of drones deployed to health centers in its network to deliver blood and medical supplies. In 2016, Zipline began delivering blood to remote hospitals in Rwanda. By 2019, the company had expanded to provide a nationwide service, delivering 75% of the country’s blood supply outside of the capital city of Kigali. The company now has a network across all of Rwanda and half of Ghana, covering over 2,500 health facilities and 25 million people from six distribution centers. It distributes blood and blood components, essential medicines, vaccines, and small medical devices. In Ghana, the company expanded its existing delivery program to include COVID-19 vaccines, transporting 11,000 doses in three days. The company has managed to see this significant growth due to value addition and integration into the existing supply chain network, according to Israel Bimpe, Africa go-to-market director at Zipline. “That allows us to be very integral of the health system and the supply chain system of medical products,” he said, adding that “when we are integral in that way, it unlocks new ways of cooperating.” “If you can get to 10 million people served by drones, well all of a sudden the maths is very different. It starts to save money.” --— Peter Liu, managing director, Deloitte US Though Zipline has managed to scale up its operations to national levels, many projects on the African continent have succumbed to what industry experts call “the valley of death” — the phase between pilots and large deployments in which the economics of drone delivery make sense. Experts say sustainable funding and diverse business models are key to avoiding this pitfall and ensuring that drones can continue to have an impact on African health care systems. A recent report by the World Economic Forum and Deloitte highlighted that although Africa has been a global leader in drones — and hosted numerous projects proving the technology works and increases efficiency — projects still fail to secure follow-on funding to scale. Data gathered by researchers showed that many projects rely on funding from international donor organizations, as well as government funds, and that they are financially challenged, despite having a substantial impact on local health outcomes. The funding is usually adequate to establish a pilot, but it is often insufficient for sustaining a program in the long term and can be affected by changes in administrations, priorities, or overall funding availability. Health supply chain services in most African countries are donor-funded, and donor procurement at the moment is geared almost exclusively toward traditional ground transport. Though they may want to invest in drones, donors are under pressure to compete with more basic programs that provide for everything from education to nutrition, according to Peter Liu, managing director at Deloitte US. Multilateral donors and the private sector may also be reluctant to invest in drones because there isn't enough evidence of their impact on health systems, the supply chain, and cost-effectiveness, said Olivier Defawe, solution owner for VillageReach’s Drones for Health program, which “aims to improve access to vaccines, lab samples and medical products in low-resource environments and hard-to-reach areas.” This is because short-term programs for which funding is available don’t allow implementers to generate much data. VillageReach is currently running Drones for Health in the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Malawi, and Mozambique. In 2020, VillageReach, along with partner Swoop Aero, took over the management of a drones network program in southern Malawi from UNICEF, after U.K. aid money for the project ceased. The partners are self-funding operations while continuing to raise money. Increased — in addition to sustained — funding is also needed to scale up projects, Liu said. Securing whole or partial funding from a country or state health budget is one path to sustainability, he added. The governments of Rwanda and Ghana have allocated permanent budgets for Zipline’s monthly operations through their ministries of health. This has been key to the success of the company's operations there, Bimpe said. “To be able to reach this level of scale where you can serve up to 300, up [to] 500, or even 700 health facilities from each distribution center — that scale is only guaranteed by the government,” he said. “Most of the health facilities are government-owned and government-operated, so their buy-in is extremely important.” For Liu, another path to sustainability lies in diversification through expansion to nonmedical uses and ensuring that the service provides for a larger population. “If you can get to 10 million people served by drones, well all of a sudden the maths is very different. It starts to save money, actually,” he said. “Once you get to that point where it makes simple business sense, we don't have to debate the value of those dollars; it will take off on its own.” Update, May 6, 2021: This article has been updated to clarify that VillageReach and Swoop Aero took over the management of a drones network program in southern Malawi from UNICEF.

On a quiet afternoon, a lone drone can be seen making its slow descent as it lands at Zipline’s Kayonza distribution center in eastern Rwanda. In one day, the center has made over 100 deliveries, with a fleet of drones deployed to health centers in its network to deliver blood and medical supplies.

In 2016, Zipline began delivering blood to remote hospitals in Rwanda. By 2019, the company had expanded to provide a nationwide service, delivering 75% of the country’s blood supply outside of the capital city of Kigali.

The company now has a network across all of Rwanda and half of Ghana, covering over 2,500 health facilities and 25 million people from six distribution centers. It distributes blood and blood components, essential medicines, vaccines, and small medical devices. In Ghana, the company expanded its existing delivery program to include COVID-19 vaccines, transporting 11,000 doses in three days.

This story is forDevex Promembers

Unlock this story now with a 15-day free trial of Devex Pro.

With a Devex Pro subscription you'll get access to deeper analysis and exclusive insights from our reporters and analysts.

Start my free trialRequest a group subscription Printing articles to share with others is a breach of our terms and conditions and copyright policy. Please use the sharing options on the left side of the article. Devex Pro members may share up to 10 articles per month using the Pro share tool ( ).

Rumbi Chakamba is a Senior Editor at Devex based in Botswana, who has worked with regional and international publications including News Deeply, The Zambezian, Outriders Network, and Global Sisters Report. She holds a bachelor's degree in international relations from the University of South Africa.