Many climate experts and diplomats flew directly from the United Nations climate conference, COP29, in Baku, Azerbaijan, to Busan, South Korea, last weekend to take on their next challenge: The fifth and ostensibly final round of negotiations to agree on a global treaty to end plastic pollution.

The previous round of talks in Ottawa, Canada, in April highlighted a steep divide between a large group of countries wanting a legally binding framework to curb plastic production and a smaller one pushing for “plastic sustainability,” or plastic waste management. The smaller group, mostly composed of oil-reliant nations such as Russia and Saudi Arabia, disrupted the negotiations over procedural rules, leaving contentious issues to be negotiated in Busan.

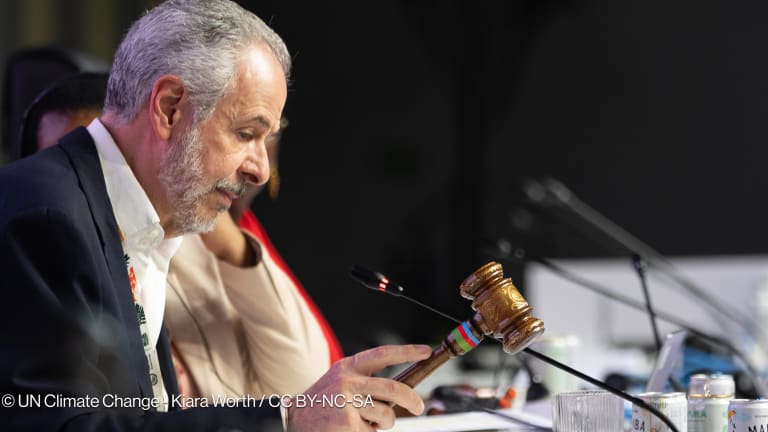

Meanwhile, long nights and tense negotiations in Baku over how to curb global warming highlighted the challenges of conducting climate talks in a polarized world, with many lower-income countries on the front lines of climate change criticizing the final COP29 finance deal as disappointing. As such, the hill appears steep for a deal in Busan, where 170 countries and over 600 observers have registered for the talks.