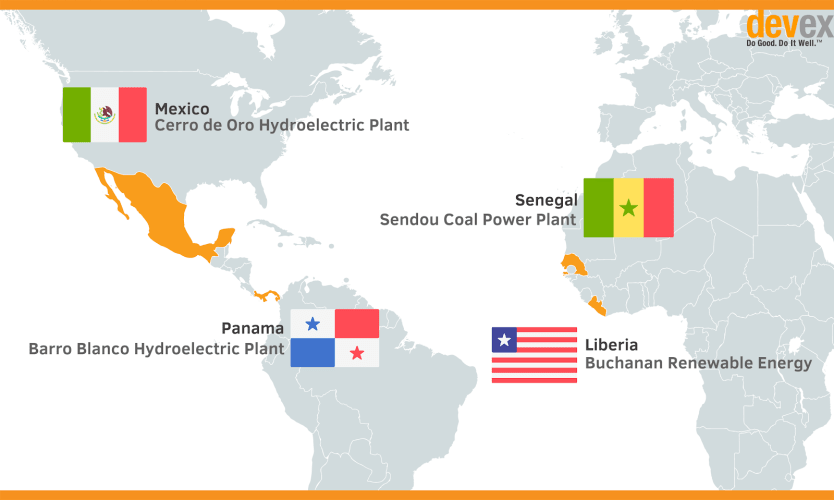

WASHINGTON — Development finance institution projects, which are playing a growing role in the global development landscape, seek to improve the quality of life and economic opportunities for host communities. But projects meant to elevate and expand the role of the private sector in development don’t always go to plan — sometimes due to a lack of strong safeguards or accountability mechanisms.

For Devex Pro subscribers: What does the data tell us about DFIs?

Devex digs into the data behind DFIs to bring you emerging financing trends.

Here’s a look at four DFI-funded projects that harmed host communities and how the lenders took lessons from those projects to adapt the way they scope, execute, and manage the work they do across the globe to prevent projects from having unintended consequences.

1. Liberia’s Buchanan Renewable Energy

Financed by: Overseas Private Investment Corporation, U.S.

The project

OPIC approved more than $200 million in loans to rejuvenate the rubber sector in Liberia between 2008-2011. Rubber trees would be cut down to be burned as wood chips and be used as biofuel, creating sustainable energy while rejuvenating family farms. Biomass company Buchanan Renewables was to construct a power plant where it would use the rubber trees to generate energy.

What happened

The project had an adverse impact on the community it was supposed to be helping by reviving the rubber sector. By cutting down their rubber trees, the project destroyed the only income source for many small family farmers and failed to help them rebuild productive farms. Buchanan was also monopolizing a key raw material needed by charcoal producers, a vulnerable population that relied on the same trees for their production. The cost of charcoal, the country’s most important fuel source, tripled in the years after the Buchanan project.

There was also alleged rampant sexual abuse by Buchanan staff, who the women said demanded sex in exchange for access to wood for their businesses. Charcoal producers had to travel further to find trees they needed and deforested more of the area. Those community members who were working for the company said Buchanan did not provide them with appropriate safety training and protective equipment. Employees suffered workplace injuries such as being trapped under fallen trees and broken limbs, and did not receive compensation or needed medical treatment.

Drinking water was also contaminated, and advocates say the communities still do not have access to clean water.

What changed

Since Buchanan withdrew from the project in 2013, the standard OPIC accountability process was not available to the communities that complained in 2014 about its lasting impact. Despite this, advocacy organization Accountability Counsel convinced OPIC to review the project. The advocacy organization participated in a review process with OPIC between 2015-2017.

After the problems with the Liberia project, in January 2017, OPIC revised its Environmental and Social Policy Statement to include stricter monitoring policies, according to OPIC spokesperson Amanda Burke. Under its 2009 version of the statement, OPIC adopted International Finance Corporation Performance Standards as the benchmark for project appraisals.

“For projects that pose a heightened risk of adverse environmental, labor, social, or human rights impacts, OPIC has supplemented the normal monitoring procedures with enhanced monitoring and reporting as the project progresses,” Burke said.

2. Mexico’s Cerro de Oro Hydroelectric Plant

Financed by: Overseas Private Investment Corporation, U.S.

The project

Cerro de Oro is a mini hydroelectric plant in Oaxaca that aimed to produce electricity to be sold to private businesses. The existing dam was to be converted into a hydropower project after the construction of a powerhouse, water intake and conduction tunnel, tailrace channel, voltage elevation substation, and transmission lines.

What happened

The project took place in an area where 20,000 indigenous people had been forcibly displaced in the 1970s and 1980s to build the original dam and were never compensated for their losses. The community felt that they were again being taken advantage of without proper consultation on how they would be impacted by the hydroelectric dam.

The outflow channel for water from the plant was directed into a creek with a natural spring that was used as a water and cultural resource. Water was contaminated by runoff from the project, and banks of creeks were deforested. This damaged fishing areas needed for livelihood and nutrition and destroyed ecosystems and indigenous infrastructure in the area.

After a complaint from the community and assessments from the Mexican government and the company involved, it was determined the site was not appropriate for a hydroelectric dam and the project was stopped. According to Accountability Counsel, most of the harm from the initial project has dissipated as trees have grown back and the spring is being cared for.

What changed

According to Stephanie Amoako, a policy associate at Accountability Counsel, one of the central complaints from the impacted communities was that the negative social and environmental impacts of the project were not sufficiently identified.

Lessons learned from the Cerro de Oro Project contributed to changes OPIC made in recent years to develop and implement more rigorous and stringent project review policies, OPIC’s Burke said.

“This includes increased focus on consultation processes and deeper historical and social consideration of a project’s local impact,” she explained. “In addition, OPIC more regularly engages additional monitoring support during project construction and operation through independent engineers and consultants. Continuing this more rigorous due diligence and oversight gives OPIC a better chance to support projects so they succeed.”

OPIC now also requires its clients to have stronger grievance mechanisms so people who feel they have been harmed by a project can effectively raise their concerns

“If properly implemented, these measures will help ensure that OPIC-supported projects properly identify and assess human rights risks for the protection of the communities affected by these projects,” Amoako said.

Accountability Counsel said it had not received any complaints about OPIC projects that were approved since the new standards were adopted.

3. Panama’s Barro Blanco Hydroelectric plant

Financed by: DEG, Germany, and FMO, Netherlands

The project

Barro Blanco is a hydroelectric power project in Panama run by a developer known as Genisa. It includes a 55-meter-high dam and a reservoir on the Tabasara river that lies less than a mile from the Pan-American highway. The $28 million project was designed to generate 140,000 MWh of reliable electricity annually, which equals more than 1.5 percent of Panama’s total energy consumption.

It was intended to supply electricity to 64,000 citizens, reducing the amount of oil the country imported. It was also designed to create local employment.

Barro Blanco was originally registered as part of the Clean Development Mechanism, the United Nations system to offset carbon. CDM projects do not have a complaint mechanism nor standards to protect human rights. After objections about the project, Panama withdrew Barro Blanco from CDM in 2016.

What happened

The Barro Blanco project raised red flags for human rights advocates before it even began, according to Anna van Ojik from Both ENDS, a Dutch advocacy organization. That organization became engaged on the case in 2010, before construction on the dam had even begun. The Comarca Ngäbe-Buglé, an indigenous group located downstream from the dam, argued their community would be adversely impacted by the flooding area of the dam.

According to FMO, all landowners were paid fair market value for their land used to construct the dam. Some landowners who owned the property where the reservoir was to be built did not want to sell, and their land was acquired under eminent domain in accordance with Panamanian law. DEG told Devex that an external investigation discovered that legitimacy of leaders from the indigenous community that had signed an agreement about the project “was being challenged by certain representatives from the indigenous community.”

For Devex Pro subscribers: Profiling 17 development finance institutions

Devex delves into analysis and commentary of 17 bilateral development finance institutions.

Genisa and the Panamanian government worked to compensate people for economic losses experienced as a result of the dam, but some members of the Ngäbe-Buglé declined to participate in a settlement. FMO said it has no control over land compensation.

“The decision on how communities should be compensated is made by the government of Panama who have set up a process to determine this,” said Paul Hartogsveld, senior communications adviser at FMO.

“FMO and our client are not party to this process so are not able to directly influence, but we are closely monitoring this and we find it important that the communities are paid as soon as possible.”

What changed

Prior to Barro Blanco, FMO did not have a complaint mechanism where communities who felt they were experiencing adverse impacts from a bank-financed project could have their grievances addressed. At the time, FMO was using the International Finance Corporation’s Performance Standards that were issued in 2006, but it now complies with the IFC’s guidelines updated in 2012.

According to DEG, Barro Blanco was the first project that used its Independent Complaints Mechanism that gives any party “who believe to be adversely affected by a project financed or planned by DEG the right to be heard and the right to complain.”

Hartogsveld said that after the complaint was filed, “it became clear from the conclusions from the panel that FMO should have taken the concerns of certain representatives from the indigenous community more seriously.” As a result, the bank issued an updated Sustainability Policy in 2017 that has “more intensive due diligence requirements for high-risk projects that have significant impact on local stakeholders.”

DEG said it now “strives for a more elaborate formal opinion from experts with defined expertise in indigenous peoples’ rights and the local legal context, on the matter of the formal representative structures in indigenous areas and will structurally consider the recommendation for future investments.”

According to DEG, it and FMO initiated a review of the Independent Complaints Mechanism in 2016 based on feedback from both banks, civil society organizations, and other parties, as well as lessons they learned after processing the first round of complaints.

4. Senegal’s Sendou Coal Power Plant

Financed by: FMO, Netherlands

The project

Sendou is a 125 MW coal power plant near the town of Bargny, a traditional fishing community on the coast near Dakar. It was designed to be the country’s most modern substation, which would contribute to a more stable power grid. The project aimed to improve access to electricity in Senegal, where FMO projected that the plant would increase the country’s supply by 30 percent and help reduce frequent energy shortages and blackouts.

Sendou was intended to supply baseload capacity for the system, which would then allow for future growth of sustainable energy including solar and wind power. To be built on 29 hectares of land, it was also meant to replace some of the country’s dependency on heavy fuel oil, which is more expensive and emits more pollution.

The plant was also designed to generate local employment, particularly for youth, during both construction and operation.

What happened

Senegal has a strong civil society that was vocal about concerns that the coal plant adversely impacted air quality and marine life, violated land rights, disregarded cultural issues, and caused economic displacement. Community advocates felt they had not been properly consulted on the potential disruptions the project would cause.

The community surrounding the coal plant had already been experiencing several environmental changes, including coastline erosion and depletion of fish supply and the nearby construction of a toll road. The plant’s construction in that location, the oversight panel concluded, limited the community’s ability to escape these other adverse factors and continue living as they always had.

In May 2016, two Senegalese NGOs filed complaints through the formal mechanism at FMO. A second complaint was filed by in July of that year, and the two were treated as one by the oversight board because they raised the same core issues with Sendou.

Their accountability study found that FMO declined to do adequate baseline studies to determine impact on air and marine life quality, how land claims would impact the local community, and establishing necessary socioeconomic data that would allow for measurement of the coal plant’s impact on local employment.

What changed

Like with Barro Blanco, the experience at Sendou contributed to the changes FMO made to its policies.

“Several key Environmental & Social (E&S) items, especially community engagement, should have been considered more carefully and contextual risk should have been better analyzed. FMO has incorporated the lessons learned from this and other projects into our policies with the purpose of improving our appraisal of E&S risks and impacts,” FMO wrote in a response to a compliance review report.

“The Human Rights position statement explicitly mentions that FMO will strengthen its approach to verifying broad community support. Furthermore, FMO has implemented the practice of publicly disclosing the high E&S risk transactions before contracting.”

These new policies will help ensure FMO is adequately aware of the entire local reality before a project begins, Hartogsveld said.

“By integrating human rights into our due diligence and investment process, FMO has widened its stakeholder engagement network, thus gaining more eyes and ears on the ground where our investments are,” Hartogsveld said. “This enables us to better understand the context in which the project is set.”

FMO now discloses all of its transactions before contracting, and employs 35 environmental and social officers. The bank no longer invests in coal projects and said it intends to continue growing its green portfolio.

Update, March 28, 2019: This article has been updated to clarify details of the project in Liberia.

Search for articles

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5