When Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus takes the helm of the World Health Organization in July, he’ll have an additional $28 million flexible funding at his disposal to use where necessary.

That could have been more — as much as 10 percent of member states’ assessed contributions, or $93 million — but WHO was in a pinch. While some member states had no qualms over increasing their contributions, some were ambivalent about outgoing Director-General Margaret Chan’s 10 percent ask. Others completely opposed any increase.

So as often is the case in international agreements, the secretariat and member states agreed on a compromise: WHO will have its increase, but only as much as 3 percent of its original request.

“In one way you could say it’s all arbitrary, because it started with 10 percent. But it was to find a level which could be acceptable for all member states,” Hans Troedsson, WHO assistant director-general for general management, told Devex at the 70th World Health Assembly taking place at Palais des Nations in Geneva, Switzerland.

But the increase, no matter the size, allowed the organization some room to celebrate. To WHO, it was a clear message of trust in the agency, which faced criticisms in its handling of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, leading to member states asking for a review and reform of the organization’s work, particularly in responding to public health emergencies.

See more related topics:

► The next WHO director-general is Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus

► A 'new era' for WHO as first African head elected — but challenges await

► Opinion: How new Director-General Tedros must modernize WHO's engagement with the world

The additional funding, Troedsson said, allows Chan — and later on Tedros — to allocate it at will, during emergencies, or to cover a shortfall in a priority public health program. Chan used assessed contributions to rescue the new health emergencies program during its establishment. Donors and member states had first wanted results before investing in the program.

“It was a little bit chicken and egg then as we say, ‘how can we deliver without any resources?’ So what the director-general rightly did then was … make an investment with some of the flexible funds to get the program started, and it has paid off,” the senior official said, noting the program has attracted voluntary contributions.

But this financing arrangement isn’t sustainable, and will need to change in the future, along with the way WHO does prioritization and how it calculates for efficiencies.

Redefining WHO’s priorities

At present, WHO’s prioritization starts in-country: WHO country representatives, together with ministries of health, identify up to 10 country health priorities. This helps feed into regional priorities. At the global level, priorities are largely influenced by resolutions agreed to by member states.

Sometimes, some programs can suffer, such as noncommunicable diseases, due to underfunding. A common criticism among civil society and those from developing countries is how WHO’s priorities are often shaped by its Western donors.

But where Troedsson suggests the need for change is, is in the role WHO plays for different health issues. WHO, he said, needs to find where it has a comparative advantage; that “unique role that no other partner or stakeholder has.”

He categorizes this into three: Proactive, reactive and passive.

Proactive is where WHO needs to take a lead, such as on antimicrobial resistance, and the issue of universal health coverage. The organization should take a proactive role in defining what UHC is, identifying the barriers toward UHC and how countries can incorporate it in their national health policies and strategies.

Reactive is where WHO needs to respond, such as to a problem a member state has raised, even though the situation or problem isn’t an emerging global public health issue or a result of a resolution.

Troedsson shared his experience in Vietnam in the 1990s, when he was country representative there as an example. The Vietnamese government asked WHO for support in developing organ transplantation legislation.

“We don’t have a big unit or anything on this one, and I don’t have the expertise in my office, but I couldn’t leave it either as for Vietnam this was a priority,” he said. So WHO, acting somewhat a broker, sought help from the French government, which then sent someone knowledgeable on the topic.

Passive means WHO not trying to create projects or initiatives in areas it does not have competence or capacity, but helping advocate for these, especially if the issue is a strong determinant for good health.

“The classic passive thing, you know what that is? In health? Women’s education,” the assistant director general said. “[It’s] one of the most important determinants for good health, not only for the woman but also for the family.”

While WHO shouldn’t start developing programs for this, it can support it through advocacy and through closer collaboration with other United Nations agencies.

“We don’t do anything actively, but in the [outgoing] director-general’s speech, she should recognize that. We should support UNESCO and others [that] want to do it,” he said. “We have to avoid the ‘this is my turf, this is your turf’ [mentality]”.

In addition, WHO should stop looking at value for money through the lens only of achieving cost savings. In the long term, Troedsson said this could prove to be more expensive, as WHO experienced when it decided to lay off almost 1,000 staff members in the African region during the financial crisis of 2011. The organization was able to save cost in the immediate term, but lost professional administrative officers.

At this year’s World Health Assembly, the U.N. aid agency came out with a paper that looks at five key elements that make up the concept of value for money: Economy, efficiency, effectiveness, equity and ethics, and at which stages of WHO’s work should each be observed.

Member states have asked WHO to present a more comprehensive paper on how this concept can be integrated and implemented in WHO’s program budget planning and operations in the future. That report is expected to be presented to the executive board in January 2018.

The way forward for the new director-general

The new director-general, Tedros, has already shared ways on how he plans to boost WHO’s fundraising capacities and chances of securing more financial commitments. In his first press conference after the election, he spoke of upsizing the WHO’s fundraising unit, building back confidence in the organization, gathering champions, and bringing the discussions on budget locally.

But ensuring the health emergencies program doesn’t suffer from underfunding will be critical. Tedros should also find ways to attract financing for the chronically underfunded NCDs.

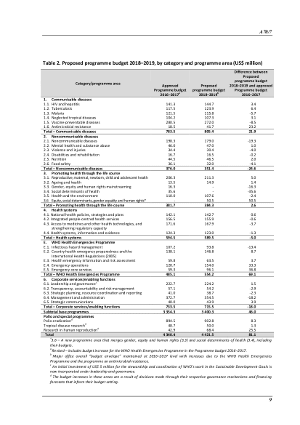

Despite having been made a high priority by member states, the program budget for NCDs in the 2018-2019 biennium has been slashed by 24.6 percent to $351.4 million, from $376 million in 2016-2017. A representative from Egypt highlighted the decrease during the session on budget, arguing this is “not the right budget [to] be sent” to the third high level meeting on NCDs in 2018.

The reductions in NCDs and other budget categories such as corporate services and health systems were made to “partially offset increases” in the health emergencies program and AMR (by $23.2 million), according to the budget document. But within categories, several budget reductions are also observed, such as malaria under communicable diseases, and health and the environment under the category promoting health through the life course.

The delegate also raised alarm on the continued underfunding of WHO’s contingency fund, which has a balance of less than half of its $100 million goal.

For Troedsson, the challenge for Tedros is ensuring he gets the program budget fully funded and have all program areas and offices fully operational throughout the next biennium, 2018-2019.

“You just can’t use the flexible funds in one area and one major office, and leave others behind,” Troedsson said. Discrepancies between overfunded and underfunded remain a huge concern.

One area Tedros should also be wary of is travel. Just before the start of the World Health Assembly, the organization came under fire for its high travel expenses in an AP report. Troedsson expressed disappointment on the report, saying much of the information presented in it were “wrong” and insisted that a huge part of the organization’s travel expense last year — around 60 percent or $120 million of the $200 million — cover nonstaff travel, which include the airfare and per diem of member states from least developing countries that attend the World Health Assembly as well as that of experts WHO tapped for its technical meetings.

“Staff travel is around $78 million, and it’s [linked to program activities] and quite strictly regulated. So the kind of staying at $1000 hotel [ ... per] night, yes, if they pay it themselves,” the assistant director-general said. “The director-general might have stayed at a hotel that charged $1000 per night, but then it’s the host government who is providing this one.”

WHO, he emphasized, has put in place strict regulations in travel — no more first class travel, and business travel may be allowed for flights exceeding nine hours — and has reported a reduction of 14 percent in travel cost in 2016.

But while the impact on member states appeared minimal, and member states have agreed to increase their contributions to the organization at the Assembly, displays of alleged excessive spending could have huge implications on the organization’s future fundraising efforts, especially as member states raise concerns on funding gaps across offices and programs, and demand tangible results in return for resources.

“Communicating tangible results is all important for member states and partner confidence, and thereby all important for securing further funds,” a representative from the United Kingdom said during the budget session.

Read more international development news online, and subscribe to The Development Newswire to receive the latest from the world’s leading donors and decision-makers — emailed to you free every business day.

Search for articles

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5