On Thursday at 11 a.m., two weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine, the country’s commissioner for human rights Liudmyla Denisova posted on Telegram that 71 children had died and more than 100 had been injured.

This included two children and their mother killed by Russian mortar fire as they fled the town of Irpin near Kyiv on Sunday. And a child was killed Wednesday, when a Russian airstrike hit a maternity and children's hospital in the city of Mariupol.

“For Russia's military invasion of Ukraine, the atrocities of Russian militants, and the violation of all Geneva conventions, Ukraine is paying an exorbitant price — the lives of its children, the future of our people,” said Denisova.

More on the war in Ukraine:

► The state of humanitarian aid in Ukraine (Pro)

► Attacks on health care in Ukraine ‘increasing quite rapidly,’ says WHO

► The globaldev organizations hiring in response to Ukraine crisis

While the child death toll rises in Ukraine, NGOs and aid agencies in-country are trying to protect Ukraine’s 7.5 million child population. In neighboring countries, development professionals are helping more than 1 million child refugees. Aid workers on the ground told Devex the children desperately need psychosocial support. The global community should also protect the most vulnerable from family separation, and from developing acute mental health problems in the future, experts said.

A moment of ‘normality’

UNICEF has about 140 staff members in Ukraine delivering aid and psychological support to children in six areas: Donetsk, Kramatorsk, Kyiv, Luhansk, Lviv, and Mariupol. UNICEF Poland spokesperson Monika Kacprzak told Devex the organization had 13 mobile units delivering clean water, blankets, and psychological support to families. “The situation is very, very difficult, but we are there,” she said.

Getting aid into Ukraine is challenging because infrastructures such as roads and bridges have been damaged, fuel and electricity are in short supply, and land mines and unexploded bombs lie on the ground, said Kacprzak. Staff safety was a priority, she added, but the majority of the Ukrainian team chose to stay.

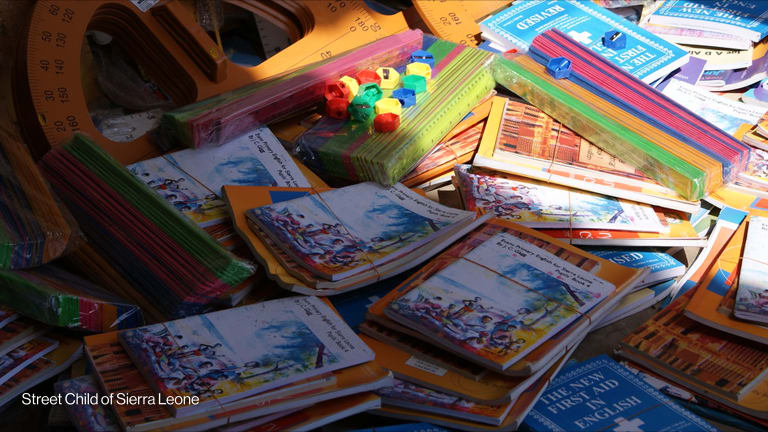

“Delivering psychological support is extremely important,” Kacprzak explained. “The children don't understand what’s going on. They have often been separated from their fathers because they are going off to fight. They are left with their mothers and grandmothers, who are also in terrible psychological states.” UNICEF’s psychologists try to explain what is happening and give the children some normality — perhaps a toy or educational materials. “They tell them things will be ok,” Kacprzak said. “But of course, we can't say this for certain.”

Outside of Ukraine, in countries to which refugees have fled, UNICEF is setting up “blue dots” — tents on roadsides where refugees can access water, food, medical help, and a moment of respite. Kacprzak said these are already operating in Romania and Moldova, and UNICEF is currently establishing more in Poland.

On Friday, March 4, staff of Lumos woke up to bombings that had struck a school where it worked in the Zhytomyr region. Fortunately, it was empty. The charity has three colleagues currently on the ground and 20 “young advocates,” young adults who were raised in children’s institutions and now work for Lumos.

Tricia Young, director of global systems change at Lumos, explained that historically, in former Soviet republics, the state placed children born with disabilities into residential care. Ukraine has among the highest number of children in institutions in Europe — around 100,000 before February’s invasion. Lumos supports Ukrainian authorities to reform the care system by reintegrating children with families or foster families.

“At the beginning of the crisis, there were 1,500 children trapped in orphanages in Zhytomyr,” she said. “Most of those have been rapidly returned to their families or foster families.” Lumos staff have so far focused on providing them with emergency aid such as food and medical equipment. Lumos has also shared resources to families containing advice and guidance on how to support children psychologically, distributing them via WhatsApp and other messaging services.

Ukraine says war damage exceeds $100B, warns of food crisis

A top adviser to Ukraine's president warns of mounting economic damage from the war with Russia and the severe effects that the rest of the world could see, including a food crisis. He asks for international support.

Young said it was vital that child-focused organizations ensure children from institutions were not separated from families. “There are some children being evacuated wholesale from institutions and taken across the border,” she said. “This risks permanent family separation.” Family tracing and reunification are complicated by war, Young explained, warning that as refugee numbers increased, so would cases of unaccompanied children fleeing the country. She urged authorities to place such children in emergency foster care, rather than institutions.

British NGO Save the Children has been operating in Ukraine since 2014, including in the conflict-impacted regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. James Denselow, head of conflict and humanitarian policy and advocacy at Save the Children, told Devex the organization had worked directly, and with partner organizations to support some 400,000 children on both sides of the “contact line,” which separates government and nongovernment controlled areas.

It now plans to upscale that work across the country, when safe, particularly delivering mine awareness and mental health and psychosocial support.

“We are distributing essential food and hygiene packs through a partner of ours called Slavic Heart,” he said. “We'll be doing more online psychosocial support sessions. None of our staff have left the country — there's not, at this stage, the desire for them to do so.”

Swiss children’s aid organization Terre des hommes was forced to suspend its activities in Kyiv and the Donbas region last week for security reasons. The organization’s psychologists have supported 10,000 children since 2015 in the conflict-affected eastern regions.

Tdh spokesperson Ivana Goretta said the organization was now focused on setting up psychosocial support for Ukrainian refugee children “in the coming days” in Hungary, Moldova, and Romania. And then with partners in Poland and Slovakia “depending on the funding we receive.”

All children were likely to be experiencing symptoms of anxiety, such as “trauma, nightmares, difficulty sleeping, hypervigilance, and ‘shutting down,’” Victoria Burch, a clinical trustee at Action for Child Trauma International, told Devex. As a result, some would develop post-traumatic stress disorder.

But she said this risk could be mitigated if children could “get really good support from loving, caring adults, be given some stability, get back to some sort of a normal life and feel safe.”

“Delivering psychological support is extremely important. … The children don't understand what’s going on.”

— Monika Kacprzak, spokesperson, UNICEF PolandGrants for local organizations

Child-focused organizations without a presence in Ukraine are also responding. U.K. charity Street Child, which supports disadvantaged children, including in conflict-affected Afghanistan, announced a Ukraine appeal promising to pass on 100% of donations to local organizations.

So far, CEO and founder Tom Dannatt has handed grants to two local Ukrainian groups: £5,000 ($6,555) to Posmishka UA, a women-led NGO in Zaporizhzhia, a city in southeastern Ukraine, which is organizing emergency aid packages for children and families; and £2,000 to Bright Kids Charity in Kyiv, which cares for underprivileged children.

Under the circumstances, Dannatt’s team has been unable to undertake the usual level of checks before providing funding. But he expects the organizations to report on their spending. “This is very brave funding,” Dannatt told Devex. “Small community-based groups hopefully can make a difference very quickly. Large NGOs or U.N. agencies are not willing to accept that degree of risk.”

Dannatt said the money collected by his organization was not being diverted from other programs, such as in Afghanistan. “We recognized a lot of our supporters were going to want to give to Ukraine,” he explained. “We said, okay, we’ll take some of that and do our best with it.”