Are abortion rights at risk as African governments negotiate with US?

As African governments sit down with U.S. negotiators to reshape health partnerships, researchers are warning that abortion access could be caught in the crosshairs.

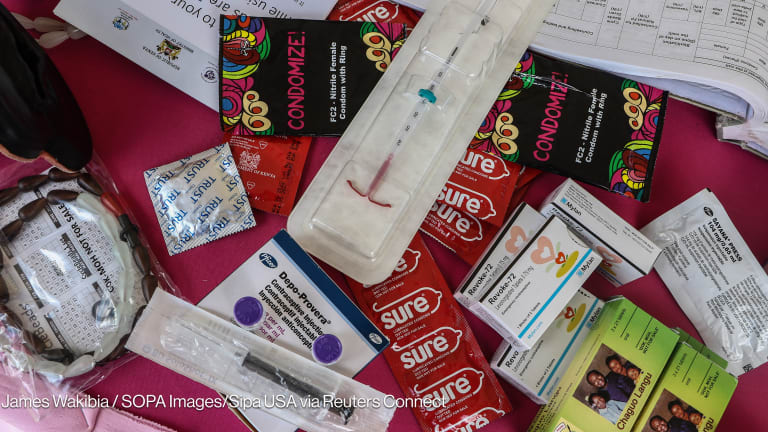

A new regional study shows that abortion rights in West and Central Africa often exist in law but not in reality — a disconnect researchers fear could deepen as African governments negotiate new, bilateral health agreements with the United States. Research, conducted by Rutgers and the Centre de Recherche en Reproduction Humaine et en Démographie, or CERRHUD, found that women and girls in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, and Cameroon faced barriers in accessing safe abortions, including overlapping systems of law, health care, and social norms, despite the countries ratifying the Maputo Protocol. The protocol is the first international treaty to recognize abortion as a human right under certain circumstances. That gap, researchers warn, could grow even wider under shifting global health politics. Jonna Both, senior researcher at Rutgers and a co-author of the report released last month, warned that the United States' bilateral agreements with African countries could further exacerbate these challenges. U.S. President Donald Trump reinstated the Mexico City Policy in January, cutting off federal funding to international nongovernmental organizations that provide abortions or even information about them — regardless of whether those services are supported by other donors. Earlier this month, State Department officials consulted with local faith-based organizations during their ongoing tour of African countries, where teams are negotiating bilateral health agreements. “What’s scary is that the U.S. government is having conversations with African governments where they try to re-establish some form of aid, but under strict conditions, and that's where they could also bring in a lot of values, conservative values,” she told Devex. “They could really make this crisis for women in those countries much, much worse.” Anti-abortion faith-based groups have long played an active role in shaping policies in Africa. In Sierra Leone, the Inter-Religious Council has opposed efforts to legalize abortion up to 14 weeks, while in Uganda, its counterpart has spoken out against proposals to ease abortion restrictions. In November, Uganda’s Constitutional Court upheld the country’s abortion laws, ruling that they protect the right to life of unborn babies and uphold family values. Onikepe Owolabi, Guttmacher Institute’s vice president for international research, who was not involved in the report, said while some faith-based organizations did valuable work, countries should be wary of the clauses in contracts that allowed them to deliver discriminatory services, as healthcare needed to be evidence-based. Countries must also have safeguards in place so that as they accept funding from the U.S. government or continue to negotiate with them, they aren’t sacrificing their own right to implement laws, policies, and training that benefit women, she added “If the U.S. has its current narrative — and it's very anti-gender and anti-rights — and you want women in your country to thrive, you should not adopt that policy narrative,” Owolabi told Devex. On the ground, the findings paint a stark picture. The research, which aimed to inform funders, donors, and others, found that many women and girls did not even know that they had a legal right to an abortion. Both said that they were symbolic of a larger group of women forced to undergo an unsafe abortion in sub-Saharan Africa, even though the community had the technical expertise to stop this. Unsafe abortion remained one of the leading causes of maternal death in sub-Saharan Africa, resulting in an estimated 15,000 preventable deaths each year, according to research and policy organization Guttmacher Institute. Access to safe abortion care following sexual violence remained a critically under-studied area, according to Rutgers. “The biggest takeaway is that the rights on paper that we have found are in place, are really not enough, and there's so much more to be done to ensure there's access to justice and to safe abortion for survivors of sexual-based violence, but also it’s a really preventable crisis,” said Both. In West and Central Africa, one of the riskiest places in the world to become pregnant unintentionally, an estimated 2.3 million unsafe terminations occurred annually, according to the Rutgers report. The Guttmacher Institute has estimated that cuts in global health funding could deny modern contraception to around 47.6 million women and couples — potentially resulting in 17.1 million unintended pregnancies and 34,000 preventable pregnancy-related deaths worldwide. In one scenario in Burkina Faso, a 16-year-old was raped by her uncle and gave birth after her boss sent her home from work, the report found. Thrown out of home, she told researchers that she would have opted for an abortion if she’d known about the law, which allows it before the end of the 14th week of pregnancy in cases of rape and incest. But there were some signs of progress. In 2021, a law was amended in Benin because maternal mortality remained high. It established a markedly broader legal framework in comparison with other countries in the region, now allowing terminations in four situations, including rape or incest, before 12 weeks of gestation. Rutgers is conducting a study on the results of the law, set to be released next year. But Marieke van der Plas, executive director of the organization, said the positive impact on women and girls was already evident. “Despite these challenges, a growing movement of organizations and advocates is standing firm, refusing to yield to policies that worsen inequalities and disproportionately put women and girls at risk,” she said. Dr. Komi Mena Agbodjavou, a co-author of the report, said that the trend was clear: When international aid decreased or became politicized, the most vulnerable women and girls paid the price. “When a program loses funding, services are reduced, staff are no longer trained, and referral networks break down, even though these are the mechanisms on which survivors depend,” he said. “Self-censorship or closure of local organizations, especially when funding imposes restrictions, exacerbates the lack of information and support available to women and young people.” The report recommended that medical procedures be separated from legal procedures to remove procedural barriers and protect victims and survivors of sexual violence, and that information on safe and legal abortion be made readily accessible. Governments and civil society must strengthen efforts to address stigma and disinformation, and abortion and gender based violence policies must be aligned. Governments could also follow the examples of Benin, Ethiopia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo by reforming abortion laws, the research said. International donors and funders must support the efforts of governments to continue to prioritize and invest in sexual and reproductive health rights and combat sexual and gender-based violence by supporting information and education programs in partnership with national stakeholders. Van der Plas said donors and funders should remain committed to rights, even in the face of adverse political developments. “The moment we are in is a defining test of our collective commitment to justice and care,” she said. “It is time for moral leadership.” The U.S. State Department did not respond to Devex’s repeated requests for comment.

A new regional study shows that abortion rights in West and Central Africa often exist in law but not in reality — a disconnect researchers fear could deepen as African governments negotiate new, bilateral health agreements with the United States.

Research, conducted by Rutgers and the Centre de Recherche en Reproduction Humaine et en Démographie, or CERRHUD, found that women and girls in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, and Cameroon faced barriers in accessing safe abortions, including overlapping systems of law, health care, and social norms, despite the countries ratifying the Maputo Protocol. The protocol is the first international treaty to recognize abortion as a human right under certain circumstances.

That gap, researchers warn, could grow even wider under shifting global health politics.

This article is free to read - just register or sign in

Access news, newsletters, events and more.

Join usSign inPrinting articles to share with others is a breach of our terms and conditions and copyright policy. Please use the sharing options on the left side of the article. Devex Pro members may share up to 10 articles per month using the Pro share tool ( ).

Amy Fallon is an Australian freelance journalist currently based in Uganda. She has also reported from Australia, the U.K. and Asia, writing for a wide range of outlets on a variety of issues including breaking news, and international development, and human rights topics. Amy has also worked for News Deeply, NPR, The Guardian, AFP news agency, IPS, Citiscope, and others.