Presented by RADIAN

Across Africa, countries are still contending with U.S. foreign aid cuts initiated more than a year ago — but nowhere more than South Africa. The country not only suffered under the dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development and the termination of many of its programs, but also a countrywide block on foreign assistance implemented by the Trump administration and high U.S. import tariffs.

This is the culmination of years of pressure on South Africa from America’s far right, which was exacerbated when Pretoria brought a genocide case against U.S. ally Israel at the International Court of Justice in 2023.

As a result of America’s actions, South Africa’s public health system is struggling, and the country’s most vulnerable residents are going without care. HIV programs have been particularly affected: An estimated 222,000 people across South Africa have had their HIV services disrupted, according to UNAIDS.

South Africa’s government is scrambling to revive services, and the country is drawing new support from China, as well as donors such as the Gates Foundation and Wellcome. But it is a challenge to recover all of the people forced out of the system over the past year.

Those South Africans are not the only ones in danger of being lost. The Trump administration has also shuttered the DREAMS program, which not only connected girls and young women around the world to HIV services but also encouraged them to stay in school or to look for job opportunities.

The cancellation of the program, which ran in 15 countries, including 10 in Africa, has left young women more vulnerable, not only to acquiring HIV, but also to dropping out of school and to unwanted pregnancies.

Read: After US aid cuts, South Africa’s HIV response strains to hold the line

Plus: Life after DREAMS — Kenya’s girls navigate HIV risk without US support

Permanent scars

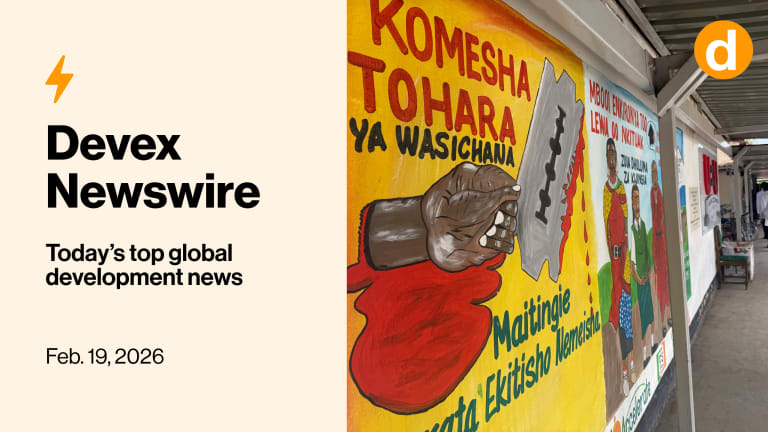

The impact of global funding cuts extends beyond HIV services. Efforts to prevent female genital mutilation in places such as Kenya are also suffering, as my colleague Sara Jerving reports, and survivors have watched many of the medical services they relied on disappear or diminish.

A joint program to end FGM in 18 countries, including Kenya, run by two United Nations agencies, has seen its budget slashed from $29.6 million in 2024 to $15.5 million last year, with only $5.6 million confirmed for this year. That includes the loss of $5 million in annual support from the United States.

FGM introduces lifelong complications for survivors, particularly during childbirth. The practice can leave scar tissue that obstructs labor and raises the risk of maternal and neonatal deaths. Health workers say they also see high rates of postpartum hemorrhage, eclampsia, and fistula in women who have undergone FGM. Some of these complications are particularly dangerous in settings without steady supplemental blood supplies.

The impact of U.S. aid cuts stretches beyond the reduction in support for programs specifically targeting an end to FGM. Washington was also funding health workers skilled in complicated deliveries and supporting community health workers who could monitor women and girls at particular risk. As many have lost their jobs, this has removed an additional lifeline for FGM survivors.

Explore the visual story: Steep aid cuts put slow gains against female genital mutilation at risk

Coming up

With health challenges in Africa steeper than ever, can Dr. Mohamed Yakub Janabi find some answers? As the newly appointed head of the World Health Organization’s office for Africa, it will be his job to help lead the continent through this difficult period.

In one of his first major public appearances, he is joining Sara for a Devex Pro Briefing this Friday, Feb. 20, to discuss, among other issues, the implications of global funding cuts and the role that WHO can play in mitigating them amid its own financing challenges. The session will also include an audience Q&A with Janabi.

+ This is a free event for Devex Pro members. Save your spot by registering ahead of the event here. Not a Pro member? You can upgrade or sign up for a free trial when registering for this event.

Agenda setting

Janabi’s Devex Pro Briefing comes nearly a week after the African Union Assembly of Heads of State and Government, where he joined three other global health leaders in pushing to ensure maternal and child health was on the agenda.

With Jean Kaseya, who heads the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; the U.N. Population Fund’s leader Diene Keita; and Rajat Khosla, executive director of Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, Janabi wrote an opinion article for Devex calling for leaders to take steps to protect MCH, including:

• Covering the costs of primary health care, particularly maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health

• Looking for other funding sources, including pooled procurement and blended finance

• Scaling regional manufacturing

Opinion: Africa’s future depends on investing in women, children, adolescents

+ Catch up on our reporting on The future of global health — a new series that explores the consequences of cuts to foreign aid and the search for a new path forward.

Back on track

After three long years, cholera prevention campaigns have finally resumed in some of the communities most at risk of an outbreak.

Your next job?

Program Officer, Health Innovation and Strategy Implementation

Gates Foundation

China

Though cholera kills as many as 143,000 people every year, preventive efforts stalled after one of the two manufacturers of the oral cholera vaccine ceased production in 2022. Officials were forced to route the limited supplies to places experiencing outbreaks.

At the same time, they worked with organizations and alternative manufacturers to ramp up production. The result was a doubling of global supply from 35 million doses in 2022 to 70 million last year, which has allowed prevention campaigns to restart.

Vaccines have already arrived in Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and shipments are expected soon in Bangladesh.

Read: Cholera prevention campaigns resume after years of vaccine scarcity

Another round

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, or CEPI, is still on a 100 Days Mission.

As part of its new CEPI 3.0 strategy, the organization maintains its goal of being able to develop and deploy a safe and effective vaccine within 100 days of identifying a new pandemic threat.

This has been a core component of its current strategy, which ends this year. And CEPI has made progress, building out a portfolio of vaccines and manufacturing capacity on a worldwide scale.

To keep going, the organization estimates that it will need to raise $2.5 billion more for its work between 2027 and 2031.

Read: CEPI seeks $2.5B to address health threats, including AI-enabled risks

Go your own way

The United States may have turned its back on WHO, but California, New York, and Illinois have not.

Those states have committed to joining the WHO’s Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network. This grants them access to disease surveillance data and experts who can assist in the event of an outbreak.

It’s part of a broader trend of states charting their own public health paths as the Trump administration withdraws the United States from global institutions and shifts longstanding health policy.

Read: What’s behind US states joining WHO’s outbreak response system

What we’re reading

A decline in the diamond trade has plunged Botswana into an economic crisis, leading to medicine shortages and leaving health workers to pay out of pocket to save patients. [The Telegraph]

Australia has the most expensive cigarettes in the world and, as a result, also has a thriving black market for tobacco. [The New York Times]

Higher temperatures globally mean the infectious disease chikungunya, previously confined to tropical regions, can now be spread across much of Europe. [The Guardian]