Presented by The Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation

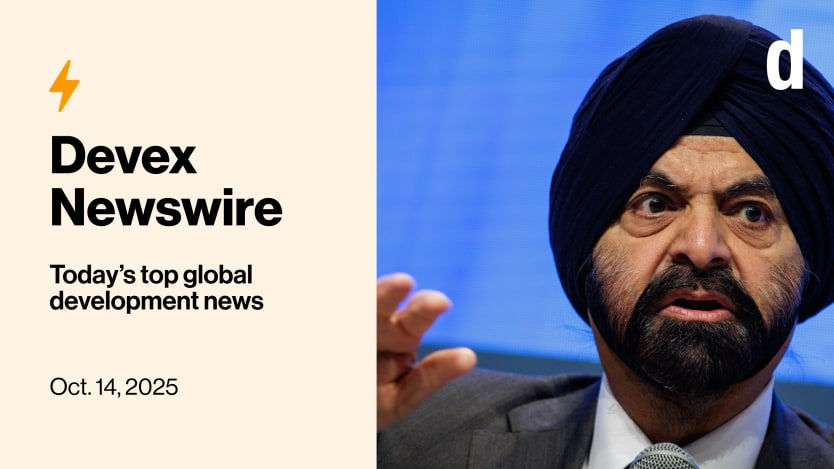

During a town hall with representatives from civil society, World Bank President Ajay Banga used the occasion to talk up his favorite subject: jobs.

Also in today’s edition: We look at a historic first for the World Bank Group, and Germany’s big (but not historic) commitment to global health.

+ During the World Bank-IMF annual meetings this week, Devex Impact House will serve as the unofficial hub for forward-looking conversations rethinking how development gets done — and who’s doing it. To request your invite to join us in person or to register for on-demand content, click here. Devex Pro members will have exclusive access to the Pro Lounge. Not a Pro member yet? Start your 15-day free trial. See you on Oct. 15-16!

Working the room

Banga can, at times, sound like a broken record when he trots out familiar job statistics — though that doesn’t diminish how stark they are.

“By 2050, more than 80% of the world’s population will live in what today we consider to be developing countries,” Banga told members of civil society at the World Bank-International Monetary Fund annual meetings yesterday. “In just the next 10 to 15 years, 1.2 billion young people will come across a labor market projected to offer just 400 million jobs — that leaves a shortfall of 800 million.”

“These are estimates, but … that’s what will define this century.”

He said jobs won’t replace other development sectors that civil society works in, such as education and health care, but that job creation is nevertheless the “goal that sits on top.”

“The idea is, how does it add up to better opportunities for young people, for dignity, for hope, for opportunity?”

Banga also outlined how the World Bank is trying to generate those opportunities through a multipronged strategy that includes providing initial public investment and guarantees to bring the private sector along for the long ride.

He cited five big job drivers: infrastructure and energy; agribusiness; health care; tourism; and value-added manufacturing, which includes the extraction of critical minerals. “They’re growth industries. They generate locally relevant jobs. They attract real investment,” he said.

A big question mark among many civil society groups was how much Banga would talk up the subject he devoted so much time to prior to the Trump administration: climate change.

The World Bank president didn’t dwell on it, nor did he shy away from it.

Climate change is not a “side effect” of the bank’s work, he said. “It is embedded in how we work and what our clients are demanding.”

That includes both physical and institutional resilience — roads that survive storms, schools that withstand heat, and farmers equipped with drought-resistant seeds. “The idea, remember, is smart development that’s resilient, that’s inclusive, and breeds trust is the only kind that will stick.”

Read: For World Bank President Ajay Banga, all roads lead to jobs

BAM!

Though Banga didn’t duck the issue of climate change, his talking points likely didn’t satisfy climate advocates who are pushing the World Bank — and other multilateral development banks — to seriously up their game.

That includes helping countries manage just transitions, whereby they wean themselves off fossil fuels and embrace a greener economy that doesn’t leave local communities behind.

A global framework called the Belém Action Mechanism for the Just Transition, or BAM, aims to require countries to follow specific standards, financing rules, and technical guidelines — and supporters want MDBs to join the effort.

“BAM is critical because it moves the conversation from dialogue to collective implementation, ensuring that climate transition benefits all, especially those currently lacking alternative pathways,” Anabella Rosemberg of the Climate Action Network says.

Another reason BAM is important: A central component is regulating critical minerals mining, which is increasingly coming under scrutiny for its harmful impacts on biodiversity and labor rights.

Crucially, it would not be a voluntary initiative led by a handful of nations or private sector groups. “It’s a multilateral approach,” Rosemberg says.

Advocates are hoping the plan will benefit from the enforcement powers of MDBs, which Rosemberg calls the “prominent actors” when it comes to channeling climate finance.

Whether MDBs want to play along is a whole other matter. So far during the annual meetings, the words “just transition” are featured in the titles of just two sessions this week, and both are being run by civil society. The word “climate” can be found in three session titles, my colleague Jesse Chase-Lubitz calculated.

“Rather than pulling back in the face of mounting challenges, we must double down on climate action and the reforms needed to finance it,” says Kevin Gallagher of the Boston University Global Development Policy Center. “The climate crisis isn’t going away, and neither are countries’ development aspirations.”

Read: At World Bank meetings, a push for UN-led ‘just transition’ framework

+ How do we go beyond emissions to rewire development in a new energy era? Are MDBs such as the World Bank ready for this new era? Watch Jesse’s video for her thoughts.

Pilot program

It was a “labor of love” more than two years in the making, says Kruskaia Sierra-Escalante, senior manager and head of coinvestor solutions at the International Finance Corporation, the World Bank’s private sector arm.

She’s referring to the World Bank Group’s first securitization transaction, which bundled and sold a share of loans from the IFC. The move allows the institution to shift from holding loans on its own books to originating and then distributing them to the private sector, my colleague Adva Saldinger writes. While the transaction does expand IFC’s lending capacity, the driving motivation was to bring more private investors into development projects across IFC’s markets.

“The ultimate objective is to really create a new asset class for emerging markets so that institutional investors can really get into that space as well,” says Mahfuza Afroz, who is the securitization project lead at IFC.

The IFC deal is backed by a portfolio of $500 million in loans to 57 borrowers spanning multiple regions and sectors. Though no immediate follow-up is planned, IFC views this as a pilot that will inform regular securitization transactions, potentially every quarter.

“We probably would have wanted to do this much faster; it took its time,” Sierra-Escalante says. “But when the moment crystallized, it was really great to see that all along the capital stack we got interest.”

Read: Unpacking the World Bank Group’s first securitization deal and what’s next

+ For more content like this, sign up to Devex Invested — the free weekly newsletter on how business, social enterprise, and development finance leaders are tackling global challenges.

Early money is like yeast?

Normally, a €300 million cut would not inspire cheers from aid advocates. But these aren’t normal times.

So when Germany announced at this week’s World Health Summit that it would commit €1 billion over the next three years to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the announcement was met with relief, even though that’s €300 million less than the country’s 2022 commitment.

The Global Fund is looking to raise $18 billion for its funding cycle between 2026 and 2028, Devex contributing reporter Andrew Green writes. Its major replenishment summit is scheduled for next month in South Africa. But Peter Sands, the fund’s executive director, welcomes Germany’s early pledge.

“Germany’s latest commitment sends a powerful signal of global solidarity and sets a strong foundation,” he says.

The pledge came at the end of a day of discussions built around a recognition that solidarity is fraying. Indeed, the theme of this year’s WHS is: “Taking Responsibility for Health in a Fragmenting World.”

With bilateral and multilateral aid plunging, much of the day’s focus was on what model the world should be transitioning to in order to preserve the gains in life expectancy earned over the past decades.

“We’re seeing that aid tumbling very fast and that suddenness is costing lives,” said UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima during one session. “Aid needs to stay there to keep as a scaffolding, as a transition.”

Read: Germany commits €1B to Global Fund as aid cuts shape World Health Summit

+ We’ll be sending a special edition newsletter on Wednesday filled with all the highlights from the World Health Summit in Berlin.

In other news

Despite global pledges to halt deforestation by 2030, forest loss has actually risen since 2021, with about 8.1 million hectares destroyed last year, putting the world 63% off track from meeting the target. [The Guardian]

A WHO analysis warns that antibiotic resistance is rising sharply worldwide, with 1 in 6 infections now drug-resistant and rates already as high as 1 in 3 in South Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Africa. [The New York Times]

A group of 165 civil society organizations sent a letter criticizing South Africa for failing to make meaningful progress on debt relief and restructuring during its G20 presidency. [Reuters]

Sign up to Newswire for an inside look at the biggest stories in global development.