LONDON — The United Kingdom Department for International Development has launched a new focus on transparency in its work with developing countries, aiming to open up their budgets to public scrutiny and better oversight.

Harriett Baldwin, joint minister of state for DFID and the Foreign & Commonwealth Office, set out the new agenda on Wednesday, inaugurating a “taxation and finance unit” within DFID, which will “sharpen the focus on transparent and effective public expenditure,” including work on improving the transparency of extractive industries in developing countries, she said in a speech.

See more related topics:

► What does the US exit from EITI mean for developing countries?

► Plans to legislate transparency of Australia's international mining operations

► Opinion: Working with local government to prevent corruption

The new unit will bring together a team of experts from across DFID and other parts of government, including the Treasury, to support a network of experts working in developing countries. The unit will also coordinate the U.K. response to donors’ collective commitment at the Addis Tax Initiative to double spending on tax capacity building by 2020.

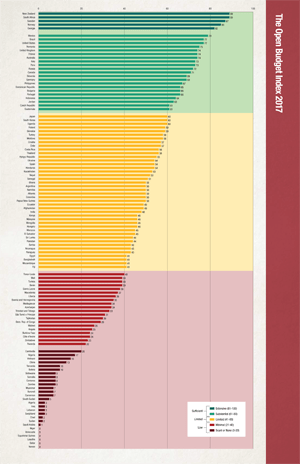

The announcement comes as the latest findings from the Open Budget Survey reveal that global budget transparency is on the decline.

Baldwin said the new “Open Aid, Open Societies” agenda will “involve more work with governments in developing countries to open our budgets, strengthening the parliamentary oversight, building supreme audit institutions, and helping citizens and the free media to scrutinize how public money and aid is spent.”

“Access to this kind of information is a right that all governments should extend to their citizens so that they know how their taxes are spent and their country is run,” she added.

Baldwin said the Open Budget Survey results, which saw transparency scores fall in 22 out of 27 countries in sub-Saharan Africa — the region with the most dramatic decline — are “of concern,” and that “it’s vital that we establish what’s behind these latest findings.”

The survey scored 115 countries on a scale of one to 100. The average was 43 in 2017, down two points from 2015 and marking the end of a steady increase in budget transparency between the first survey in 2008 and 2015.

It also found that roughly three-quarters of countries surveyed do not publish sufficient budget information, denoted by a score of 61 or higher.

The greatest decline was in countries in sub-Saharan Africa, where the average drop was 11 points. Only Asia saw a substantial increase in its score as a region, but countries including Georgia, Jordan, Mexico, and Senegal were among those with the greatest gains individually.

Vivek Ramkumar, senior director of policy at the Open Budget Partnership, said the decline is largely due to shrinking space for civil society and accountability institutions in developing countries, which would normally hold the government to account and interpret data for the public. He said that “20 percent of budget transparency issues could be solved in five minutes,” because “many low-income countries already have those documents internally, but choose not to share them with the public.”

“We find that there are countries that have relatively good public financial systems that are not delivering on transparency,” he told Devex. “Countries like Rwanda or Burkina Faso, generally well regarded in the donor community that is focused on Africa, they have done well in building up their systems, but on the transparency side they don’t deliver.”

Ramkumar said aid donors have a role to play in incentivizing greater transparency alongside improving governance and financial systems, but that they must do this work in conjunction with local civil society.

“If the results from 2017 are anything to go by, even though donors have been saying to governments that transparency is important, we’re still not necessarily seeing an improvement, and in some cases we’re seeing a regression,” he said.

“Ultimately it’s about what donors can do collectively with others to build domestic ownership of these agendas, so donors should be talking not just to the executive wing, but to other parts of government, legislatures, anticorruption agencies, civil society organizations, trying to create or support dialogue in countries, so that transparency isn’t just a bilateral conversation,” he said.

“Budget transparency suffers when aid transparency is weak.”

— Vivek Ramkumar, senior director of policy at the Open Budget PartnershipIt’s hard to say yet how DFID will press its new transparency agenda, Ramkumar added, though the broad strokes seem encouraging. The department details an ambitious to-do list, including plans to “reform the international aid system;” “strengthen existing global initiatives;” “do more in the poorest countries to open up governments;” and “spearhead new global standards” — naming the government-wide, anticorruption strategy released in December 2017 as a key step, as well as a commitment to “lead an international dialogue on global commodities training.”

Ramkumar praised Baldwin’s commitment to improve the transparency of DFID’s own aid flows as one key step toward creating sustainable, lasting accountability in-country.

“What we have seen is a disconnect between aid flows into countries and the other resources that are available domestically, and the challenge that it can create for governments to be transparent, when they don’t know if money from donors is coming in in a predictable manner, so there are not proper systems in place to be able to report on that transparency,” he said. “Budget transparency suffers when aid transparency is weak.”

“There is a relationship … between the source of money for governments coming from the extractives, particularly oil, and the nature of governance that is more conducive to opaque behaviour.”

—He also praised DFID’s promise to work on the transparency of the extractives industry in developing countries, which will hasten domestic resource mobilization and improve accountability in economies that have traditionally functioned on opacity.

“Our data has shown that some of the worst performers on transparency are the highly oil dependent countries, so there is a relationship clearly between the source of money for governments coming from the extractives, particularly oil, and the nature of governance that is more conducive to opaque behaviour,” he said. “That’s the reason why, if DFID and others are emphasizing extractive transparency, we see that as also contributing to gains on budget transparency.”

At the same time, Ramkumar cautioned DFID and other donors against forgetting lessons from the past, particularly when tempted to use aid conditionally.

After the International Monetary Fund implemented its structural adjustment policies in the 1990s, placing certain economic and governance conditions on development initiatives in developing countries, results were mixed, and donors and the IMF saw great pushback from civil society and developing country populations.

“We’ve seen, not surprisingly, the donor community moving away from the use of language like conditionality,” he said. “It’s now about ensuring there is adequate emphasis given to the whole transparency agenda, so that governments don’t feel that the only gain they get from transparency is that tranche of money, or next instalment will be available from donors, because that will then lead to gaming of the system.”

Read more Devex coverage on the future of the U.K. aid.