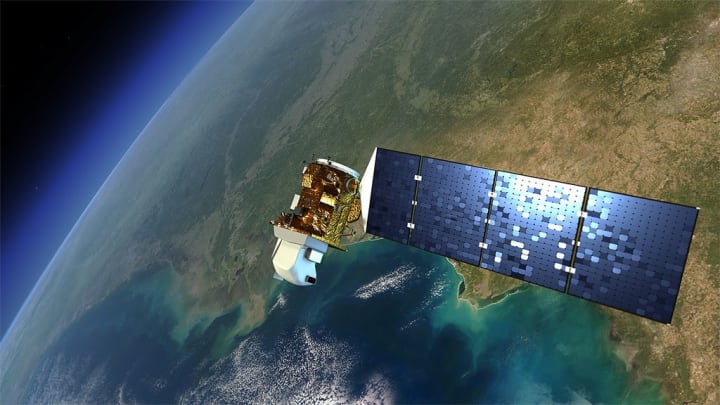

Technological advances are making satellite imagery cheaper and easier to access than ever before. A growing number of providers are even making their data accessible for free: In 2008, the U.S. Geological Survey made data from its Landsat satellites free to use, leading to a significant uptake in the use of satellite data for research and commercial purposes. The European Space Agency has also adopted a policy on free and open data for its growing Copernicus program.

“We need to … recognize that it is unlikely that there will be one specific standard and specification [of analysis-ready data] that will meet everybody's requirements.”

— Terri Freemantle, senior Earth observation specialist, Satellite Applications CatapultThis has tremendous potential for stakeholders working in various aspects of development. For example, satellite imagery can provide useful data that complements traditional data collection mechanisms such as censuses and surveys. It can supply helpful information for disaster response, track deforestation by measuring the evolution of forest cover over time, and help with urban planning by monitoring urban growth.

“Earth observation is very relevant for a number of [sustainable development] indicators, and Earth observation is extremely relevant for a number of targets,” said Marc Paganini, technical officer in the Directorate of Earth Observation Programmes at the European Space Agency.

However, despite the increased accessibility of satellite data, translating it into usable information still requires substantial skills and resources. While recent developments in data analytics have allowed some processing to become computerized and automated, the development sector has yet to adopt those practices at scale.

According to Paganini, processing satellite data provided by space agencies “requires high remote sensing knowledge,” which many countries don’t have. However, if the processing burden for any individual country is removed, “the data can much more easily be incorporated inside the country, the national system, and processes,” he added.

Making satellite data ‘analysis-ready’

Before they are ready for analysis, satellite images must be treated. For example, one common procedure is to remove the cloud cover from images by replacing contaminated pixels with clean ones. Another is to correct the haziness that can occur as a result of atmospheric disturbances — a process referred to as “atmospheric correction.”

Those steps are time-consuming and require specific technical skills. This limits the uptake of data by potential users in the development sector, many of whom may not have the human, technical, or financial resources to take on such work.

To make satellite data more user-friendly, some providers have started to offer “analysis-ready data,” or ARD. The term refers to data that’s already been cleaned of its irregularities, notably by using algorithms — thus making it more accessible to organizations that would otherwise be unable to use it.

The Norway-based company Sensonomic uses various sources of data, including satellites, to build digital models and simulations of agricultural operations. This helps farmers and other stakeholders gain insights on crop yields. As a small-to-medium enterprise, Sensonomic does not have the capital to invest in processing chains, according to CEO and founder Anders Gundersen.

“Our alternative before ARD was to buy it from a specialized remote sensing company, or to use a lot of man-hours on it, and a lot of time,” Gundersen said.

But to make ARD work at scale, the Earth observation community needs to agree on the parameters that define the quality of images and the format to be used so that all providers and users can work with standardized data. This will improve the consistency and comparability of Earth observation data, among other benefits. That discussion is taking place through the Committee on Earth Observation Satellites, which ensures the international coordination of civil space-based Earth observation programs, Paganini said.

“There are still a number of open issues that space agencies need to agree in order that everybody is working on the same level and provide the data in the same way,” he said.

Bringing ARD to the development community

The Earth observation community has been developing tools to translate the high volume of satellite data into user-friendly formats. Among these are open-data cubes — open-source frameworks in which satellite datasets are organized by space and time coordinates. This allows end users to track the evolution of Earth data — such as vegetation, land use, or water coverage — over time. In the context of sustainable development, this could mean having easy and fast access to monitoring the effects of climate change in a particular location or urbanization patterns when no census mechanisms are in place.

The CommonSensing initiative, part of the U.K. Space Agency's International Partnership Programme, has been using the data cube model to help the governments of the Solomon Islands, Fiji, and Vanuatu to use Earth observation to build climate resilience. This allows partners to access layers of data from different satellites for a given location and then analyze how pixels have changed over time, said Terri Freemantle, senior Earth observation specialist at the Satellite Applications Catapult, which is part of CommonSensing.

“This gives us a much quicker way to do things like calculate baselines and then use our baseline to monitor change,” Freemantle said. “[We can] then even potentially predict what future change might look like.”

The Africa Regional Data Cube, or ARDC, is working to bring the approach of open-data cubes to five African countries — Ghana, Kenya, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Tanzania — through partnerships with Earth observation organizations and capacity building within countries. ARDC has been mindful of ensuring that its tools are both accessible and usable, and it currently provides 17 years’ worth of layered ARD via online interfaces, thus granting countries access to a trove of historical data on their land.

“A computation or analysis that would ideally take somebody many days and weeks can be done within 15 minutes,” said Davis Adieno, director of programs for the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, one of the organizations that developed the project.

What is the International Partnership Programme?

Launched in 2015, the U.K. Space Agency’s International Partnership Programme is a £152 million ($196 million) multiyear program that uses U.K. organizations’ space knowledge, expertise, and capabilities to provide a sustainable, economic, or societal benefit to low- and middle-income countries.

It is funded by the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy’s Global Challenges Research Fund, a £1.5 billion fund that forms part of the U.K. government’s official development assistance commitment.

The tool is being used for a diversity of projects, such as monitoring deforestation in Senegal and looking at the impact of extreme weather patterns in northern Kenya. In 2018, ARDC helped Ghana’s government track illegal mining through Earth observation — which is safer, more efficient, and less expensive than running surveys on the ground. It created an algorithm trained to spot signs of illegal mines, such as new wastewater ponds.

According to Adieno, the launch of digital platforms or infrastructures creates the risk that tools barely get used by different partners. “We call it ‘death by platforms,’” he said, adding that platforms sometimes get built without input from their intended users and without making sure that there is an interest or capacity to use new tools.

In contrast, ARDC came to life as a result of previous discussions between the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data and partner countries. These revealed some of the hurdles that nations were facing when tackling sustainable development locally, including the time required to process satellite data. When the first data cube was developed in Australia, Adieno and his collaborators immediately saw the potential to use the framework in other countries.

“Through this engagement, we already identified what … the demand was. And we sought to align it with what our different country partners had identified as challenges,” he said.

To facilitate the adoption of new practices within the various government institutions in charge of handling data, ARDC is running a number of capacity-building activities, including training.

But some challenges remain in helping partner countries access Earth observation data. For example, more technical skills are needed to interpret the data and translate it into meaningful information that can support the development of policies and programs, according to Adieno. Another source of difficulty is the lack of reliable access to the internet, which can prevent countries from retrieving data that is stored in the cloud.

ARDC is working to develop additional partnerships, notably with private Earth observation providers, to increase the range of data available and improve the infrastructure needed to access it.

“This whole concept is being democratized. We're demonstrating that there is value in partnerships that can make this kind of data easily available,” Adieno said.

Taking ARD to scale

Not all users of satellite data require ARD; they may have the capacity to process the data in-house or wish to process it in different ways. Sensonomic’s Gundersen said that some commercial providers haven’t yet taken stock of all the use cases for ARD and, as a result, haven’t adjusted their prices to reflect the growing diversity of potential customers. This means that certain types of data, such as higher-resolution images, remain mostly unaffordable to the development sector, he added.

“There's a business development gap from the industry's point of view,” Gundersen said. The development community will have to involve commercial providers to demonstrate the need and demand for a broader range of satellite imagery products, he said.

The Earth observation industry is still young and maturing. With technological advances in areas such as machine learning increasing the speed at which data can be processed, the full potential of Earth observation data has yet to be exploited. And as the amount of users and products grows, ARD may ultimately evolve several standards to reflect the growing types of user needs and requirements.

“The concept of analysis-ready data is fantastic, and it breaks down the barriers of entry. But we need to, as a community, recognize that it is unlikely that there will be one specific standard and specification that will meet everybody's requirements,” Satellite Applications Catapult’s Freemantle said.

Visit the Data for Development series for more coverage on practical ways that satellite data can be harnessed to support the work of development professionals and aid workers. You can join the conversation using the hashtag #DataForDev.